There are many fun yet highly educational therapy activities we can do with our preschool and school-aged clients in the fall. One of my personal favorites is bingo. Boggles World, an online ESL teacher resource actually has a number of ready-made materials, flashcards, and worksheets that can be adapted for speech-language therapy purposes. For example, their Fall and Halloween Bingo comes with both call out cards and a 3×3 and a 4×4 (as well as 3×3) card generator/boards. Clicking the refresh button will generate as many cards as you need, so the supply is endless! You can copy and paste the entire bingo board into a word document resize it and then print it out on reinforced paper or just laminate it. Continue reading Therapy Fun with Ready Made Fall and Halloween Bingo

There are many fun yet highly educational therapy activities we can do with our preschool and school-aged clients in the fall. One of my personal favorites is bingo. Boggles World, an online ESL teacher resource actually has a number of ready-made materials, flashcards, and worksheets that can be adapted for speech-language therapy purposes. For example, their Fall and Halloween Bingo comes with both call out cards and a 3×3 and a 4×4 (as well as 3×3) card generator/boards. Clicking the refresh button will generate as many cards as you need, so the supply is endless! You can copy and paste the entire bingo board into a word document resize it and then print it out on reinforced paper or just laminate it. Continue reading Therapy Fun with Ready Made Fall and Halloween Bingo

Category: language stimulation

What are They Trying To Say? Interpreting Music Lyrics for Figurative Language Acquisition Purposes

In my last post, I described how I use obscurely worded newspaper headlines to improve my students’ interpretation of ambiguous and figurative language. Today, I wanted to further delve into this topic by describing the utility of interpreting music lyrics for language therapy purposes. I really like using music lyrics for language treatment purposes. Not only do my students and I get to listen to really cool music, but we also get an opportunity to define a variety of literary devices (e.g., hyperboles, similes, metaphors, etc.) as well as identify them and interpret their meaning in music lyrics. Continue reading What are They Trying To Say? Interpreting Music Lyrics for Figurative Language Acquisition Purposes

In my last post, I described how I use obscurely worded newspaper headlines to improve my students’ interpretation of ambiguous and figurative language. Today, I wanted to further delve into this topic by describing the utility of interpreting music lyrics for language therapy purposes. I really like using music lyrics for language treatment purposes. Not only do my students and I get to listen to really cool music, but we also get an opportunity to define a variety of literary devices (e.g., hyperboles, similes, metaphors, etc.) as well as identify them and interpret their meaning in music lyrics. Continue reading What are They Trying To Say? Interpreting Music Lyrics for Figurative Language Acquisition Purposes

Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

Creating a Comprehensive Speech Language Therapy Environment

So you’ve completed a thorough evaluation of your student’s speech and language abilities and are in the process of creating goals and objectives to target in sessions. The problem is that many of the students on our caseloads present with pervasive deficits in many areas of language.

So you’ve completed a thorough evaluation of your student’s speech and language abilities and are in the process of creating goals and objectives to target in sessions. The problem is that many of the students on our caseloads present with pervasive deficits in many areas of language.

While it’s perfectly acceptable to target just a few goals per session in order to collect good data, both research and clinical experience indicate that addressing goals comprehensively and thematically (the whole system or multiple goals at once from the areas of content, form, and use) via contextual language intervention vs. in isolation (small parts such as prepositions, pronouns, etc.) will bring about the quickest change and more permanent results.

So how can that be done? Well, for significantly language impaired students it’s very important to integrate semantic language components as well as verbal reasoning tasks into sessions no matter what type of language activity you are working on (such as listening comprehension, auditory processing, social inferencing and so on). The important part is to make sure that the complexity of the task is commensurate with the student’s level of abilities.

Let’s say you are working on a fall themed lesson plans which include topics such as apples and pumpkins. As you are working on targeting different language goals, just throw in a few extra components to the session and ask the child to make, produce, explain, list, describe, identify, or interpret:

- Associations (“We just read a book about pumpkin: What goes with a pumpkin?”)

- Synonyms (“It said the leaves felt rough, what’s another word for rough?”)

- Antonyms (“what is the opposite of rough?”)

- Attributes 5+ (category, function, location, appearance, accessory/necessity, composition) (“Pretend I don’t know what a pumpkin is, tell me everything you can think of about a pumpkin”)

- Multiple Meaning Words (“The word felt has two meanings, it could mean _____ and it could also mean _______”)

- Definitions (“what is a pumpkin”)

- Compare and Contrast (“How are pumpkin and apple alike? How are they different?”)

- Idiomatic expressions (“Do you know what the phrase turn into a pumpkin means?” )

Ask ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions in order to start teaching the student how to justify, rationalize, evaluate, and make judgments regarding presented information (“Why do you think we plant pumpkins in the spring and not in the fall?”)

Don’t forget the inferencing and predicting questions in order to further develop the client’s verbal reasoning abilities (“What do you think will happen if no one picks up the apples from the ground?)

If possible attempt to integrate components of social language into the session such as ask client to relate to a character in a story, interpret the character’s feelings (“How do you think the girl felt when her sisters made fun of her pumpkin?”), ideas and thoughts, or just read nonverbal social cues such as body language or facial expressions of characters in pictures.

Select materials which are both multipurpose and reusable as well as applicable to a variety of therapy goals. For example, let’s take a simple seasonal word wall such as the (free) Fall Word Wall from TPT by Pocketful of Centers. Print it out in color, cut out the word strips and note how many therapy activities you can target for articulation, language, fluency, literacy and phonological awareness, etc.

Language:

Practice Categorization skills via convergent and divergent naming activities: Name Fall words, Name Halloween/Thanksgiving Words, How many trees whose leaves change color can you name?, how many vegetables and fruits do we harvest in the fall? etc.

Practice naming Associations: what goes with a witch (broom), what goes with a squirrel (acorn), etc

Practice providing Attributes via naming category, function, location, parts, size, shape, color, composition, as well as accessory/necessity. For example, (I see a pumpkin. It’s a fruit/vegetable that you can plant, grow and eat. You find it on a farm. It’s round and orange and is the size of a ball. Inside the pumpkin are seeds. You can carve it and make a jack o lantern out of it).

Practice providing Definitions: Tell me what a skeleton is. Tell me what a scarecrow is.

Practice naming Similarities and Differences among semantically related items: How are pumpkin and apple alike? How are they different?

Practice explaining Multiple Meaning words: What are some meanings of the word bat, witch, clown, etc?

Practice Complex Sentence Formulation: what happens in the fall? Make up a sentence with the words scarecrow and unless, make up a sentence with the words skeleton and however, etc

Phonological Awareness:

Practice Rhyming words (you can do discrimination and production activities): cat/bat/ trick/leaf/ rake/moon

Practice Syllable and Phoneme Segmentation (I am going to say a word (e.g., leaf, corn, scarecrow, etc) and I want you to clap one time for each syllable or sound I say)

Practice Isolation of initial, medial, and final phonemes in words ( e.g., What is the beginning/final sound in apple, hay, pumpkin etc?) What is the middle sound in rake etc?

Practice Initial and Final Syllable and Phoneme Deletion in Words (Say spider! Now say it without the der, what do you have left? Say witch, now say it without the /ch/ what is left; say corn, now say it without the /n/, what is left?)

Articulation/Fluency:

Practice production of select sounds/consonant clusters that you are working on or just production at word or sentence levels with those clients who just need a little bit more work in therapy increasing their intelligibility or sentence fluency.

So next time you are targeting your goals, see how you can integrate some of these suggestions into your data collection and let me know whether or not you’ve felt that it has enhanced your therapy sessions.

Happy Speeching!

Helpful Resources:

- Creating Functional Therapy Plan

- Selecting Clinical Materials for Pediatric Therapy

- Vocabulary Development: Working With Disadvantaged Populations

- General Assessment and Treatment Start-Up Bundle

Review of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS)

The Test of Integrated Language & Literacy Skills (TILLS) is an assessment of oral and written language abilities in students 6–18 years of age. Published in the Fall 2015, it is unique in the way that it is aimed to thoroughly assess skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school age children. As I have been using this test since the time it was published, I wanted to take an opportunity today to share just a few of my impressions of this assessment.

The Test of Integrated Language & Literacy Skills (TILLS) is an assessment of oral and written language abilities in students 6–18 years of age. Published in the Fall 2015, it is unique in the way that it is aimed to thoroughly assess skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school age children. As I have been using this test since the time it was published, I wanted to take an opportunity today to share just a few of my impressions of this assessment.

First, a little background on why I chose to purchase this test so shortly after I had purchased the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5 (CELF-5). Soon after I started using the CELF-5 I noticed that it tended to considerably overinflate my students’ scores on a variety of its subtests. In fact, I noticed that unless a student had a fairly severe degree of impairment, the majority of his/her scores came out either low/slightly below average (click for more info on why this was happening HERE, HERE, or HERE). Consequently, I was excited to hear regarding TILLS development, almost simultaneously through ASHA as well as SPELL-Links ListServe. I was particularly happy because I knew some of this test’s developers (e.g., Dr. Elena Plante, Dr. Nickola Nelson) have published solid research in the areas of psychometrics and literacy respectively.

According to the TILLS developers it has been standardized for 3 purposes:

- to identify language and literacy disorders

- to document patterns of relative strengths and weaknesses

- to track changes in language and literacy skills over time

The testing subtests can be administered in isolation (with the exception of a few) or in its entirety. The administration of all the 15 subtests may take approximately an hour and a half, while the administration of the core subtests typically takes ~45 mins).

Please note that there are 5 subtests that should not be administered to students 6;0-6;5 years of age because many typically developing students are still mastering the required skills.

- Subtest 5 – Nonword Spelling

- Subtest 7 – Reading Comprehension

- Subtest 10 – Nonword Reading

- Subtest 11 – Reading Fluency

- Subtest 12 – Written Expression

However, if needed, there are several tests of early reading and writing abilities which are available for assessment of children under 6:5 years of age with suspected literacy deficits (e.g., TERA-3: Test of Early Reading Ability–Third Edition; Test of Early Written Language, Third Edition-TEWL-3, etc.).

Let’s move on to take a deeper look at its subtests. Please note that for the purposes of this review all images came directly from and are the property of Brookes Publishing Co (clicking on each of the below images will take you directly to their source).

1. Vocabulary Awareness (VA) (description above) requires students to display considerable linguistic and cognitive flexibility in order to earn an average score. It works great in teasing out students with weak vocabulary knowledge and use, as well as students who are unable to quickly and effectively analyze words for deeper meaning and come up with effective definitions of all possible word associations. Be mindful of the fact that even though the words are presented to the students in written format in the stimulus book, the examiner is still expected to read all the words to the students. Consequently, students with good vocabulary knowledge and strong oral language abilities can still pass this subtest despite the presence of significant reading weaknesses. Recommendation: I suggest informally checking the student’s word reading abilities by asking them to read of all the words, before reading all the word choices to them. This way you can informally document any word misreadings made by the student even in the presence of an average subtest score.

1. Vocabulary Awareness (VA) (description above) requires students to display considerable linguistic and cognitive flexibility in order to earn an average score. It works great in teasing out students with weak vocabulary knowledge and use, as well as students who are unable to quickly and effectively analyze words for deeper meaning and come up with effective definitions of all possible word associations. Be mindful of the fact that even though the words are presented to the students in written format in the stimulus book, the examiner is still expected to read all the words to the students. Consequently, students with good vocabulary knowledge and strong oral language abilities can still pass this subtest despite the presence of significant reading weaknesses. Recommendation: I suggest informally checking the student’s word reading abilities by asking them to read of all the words, before reading all the word choices to them. This way you can informally document any word misreadings made by the student even in the presence of an average subtest score.

2. The Phonemic Awareness (PA) subtest (description above) requires students to isolate and delete initial sounds in words of increasing complexity. While this subtest does not require sound isolation and deletion in various word positions, similar to tests such as the CTOPP-2: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing–Second Edition or the The Phonological Awareness Test 2 (PAT 2), it is still a highly useful and reliable measure of phonemic awareness (as one of many precursors to reading fluency success). This is especially because after the initial directions are given, the student is expected to remember to isolate the initial sounds in words without any prompting from the examiner. Thus, this task also indirectly tests the students’ executive function abilities in addition to their phonemic awareness skills.

3. The Story Retelling (SR) subtest (description above) requires students to do just that retell a story. Be mindful of the fact that the presented stories have reduced complexity. Thus, unless the students possess significant retelling deficits, the above subtest may not capture their true retelling abilities. Recommendation: Consider supplementing this subtest with informal narrative measures. For younger children (kindergarten and first grade) I recommend using wordless picture books to perform a dynamic assessment of their retelling abilities following a clinician’s narrative model (e.g., HERE). For early elementary aged children (grades 2 and up), I recommend using picture books, which are first read to and then retold by the students with the benefit of pictorial but not written support. Finally, for upper elementary aged children (grades 4 and up), it may be helpful for the students to retell a book or a movie seen recently (or liked significantly) by them without the benefit of visual support all together (e.g., HERE).

4. The Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest (description above) requires students to repeat nonsense words of increasing length and complexity. Weaknesses in the area of nonword repetition have consistently been associated with language impairments and learning disabilities due to the task’s heavy reliance on phonological segmentation as well as phonological and lexical knowledge (Leclercq, Maillart, Majerus, 2013). Thus, both monolingual and simultaneously bilingual children with language and literacy impairments will be observed to present with patterns of segment substitutions (subtle substitutions of sounds and syllables in presented nonsense words) as well as segment deletions of nonword sequences more than 2-3 or 3-4 syllables in length (depending on the child’s age).

5. The Nonword Spelling (NS) subtest (description above) requires the students to spell nonwords from the Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest. Consequently, the Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest needs to be administered prior to the administration of this subtest in the same assessment session. In contrast to the real-word spelling tasks, students cannot memorize the spelling of the presented words, which are still bound by orthographic and phonotactic constraints of the English language. While this is a highly useful subtest, is important to note that simultaneously bilingual children may present with decreased scores due to vowel errors. Consequently, it is important to analyze subtest results in order to determine whether dialectal differences rather than a presence of an actual disorder is responsible for the error patterns.

6. The Listening Comprehension (LC) subtest (description above) requires the students to listen to short stories and then definitively answer story questions via available answer choices, which include: “Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe”. This subtest also indirectly measures the students’ metalinguistic awareness skills as they are needed to detect when the text does not provide sufficient information to answer a particular question definitively (e.g., “Maybe” response may be called for). Be mindful of the fact that because the students are not expected to provide sentential responses to questions it may be important to supplement subtest administration with another listening comprehension assessment. Tests such as the Listening Comprehension Test-2 (LCT-2), the Listening Comprehension Test-Adolescent (LCT-A), or the Executive Function Test-Elementary (EFT-E) may be useful if language processing and listening comprehension deficits are suspected or reported by parents or teachers. This is particularly important to do with students who may be ‘good guessers’ but who are also reported to present with word-finding difficulties at sentence and discourse levels.

7. The Reading Comprehension (RC) subtest (description above) requires the students to read short story and answer story questions in “Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe” format. This subtest is not stand alone and must be administered immediately following the administration the Listening Comprehension subtest. The student is asked to read the first story out loud in order to determine whether s/he can proceed with taking this subtest or discontinue due to being an emergent reader. The criterion for administration of the subtest is making 7 errors during the reading of the first story and its accompanying questions. Unfortunately, in my clinical experience this subtest is not always accurate at identifying children with reading-based deficits.

While I find it terrific for students with severe-profound reading deficits and/or below average IQ, a number of my students with average IQ and moderately impaired reading skills managed to pass it via a combination of guessing and luck despite being observed to misread aloud between 40-60% of the presented words. Be mindful of the fact that typically such students may have up to 5-6 errors during the reading of the first story. Thus, according to administration guidelines these students will be allowed to proceed and take this subtest. They will then continue to make text misreadings during each story presentation (you will know that by asking them to read each story aloud vs. silently). However, because the response mode is in definitive (“Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe”) vs. open ended question format, a number of these students will earn average scores by being successful guessers. Recommendation: I highly recommend supplementing the administration of this subtest with grade level (or below grade level) texts (see HERE and/or HERE), to assess the student’s reading comprehension informally.

I present a full one page text to the students and ask them to read it to me in its entirety. I audio/video record the student’s reading for further analysis (see Reading Fluency section below). After the completion of the story I ask the student questions with a focus on main idea comprehension and vocabulary definitions. I also ask questions pertaining to story details. Depending on the student’s age I may ask them abstract/ factual text questions with and without text access. Overall, I find that informal administration of grade level (or even below grade-level) texts coupled with the administration of standardized reading tests provides me with a significantly better understanding of the student’s reading comprehension abilities rather than administration of standardized reading tests alone.

8. The Following Directions (FD) subtest (description above) measures the student’s ability to execute directions of increasing length and complexity. It measures the student’s short-term, immediate and working memory, as well as their language comprehension. What is interesting about the administration of this subtest is that the graphic symbols (e.g., objects, shapes, letter and numbers etc.) the student is asked to modify remain covered as the instructions are given (to prevent visual rehearsal). After being presented with the oral instruction the students are expected to move the card covering the stimuli and then to executive the visual-spatial, directional, sequential, and logical if–then the instructions by marking them on the response form. The fact that the visual stimuli remains covered until the last moment increases the demands on the student’s memory and comprehension. The subtest was created to simulate teacher’s use of procedural language (giving directions) in classroom setting (as per developers).

9. The Delayed Story Retelling (DSR) subtest (description above) needs to be administered to the students during the same session as the Story Retelling (SR) subtest, approximately 20 minutes after the SR subtest administration. Despite the relatively short passage of time between both subtests, it is considered to be a measure of long-term memory as related to narrative retelling of reduced complexity. Here, the examiner can compare student’s performance to determine whether the student did better or worse on either of these measures (e.g., recalled more information after a period of time passed vs. immediately after being read the story). However, as mentioned previously, some students may recall this previously presented story fairly accurately and as a result may obtain an average score despite a history of teacher/parent reported long-term memory limitations. Consequently, it may be important for the examiner to supplement the administration of this subtest with a recall of a movie/book recently seen/read by the student (a few days ago) in order to compare both performances and note any weaknesses/limitations.

10. The Nonword Reading (NR) subtest (description above) requires students to decode nonsense words of increasing length and complexity. What I love about this subtest is that the students are unable to effectively guess words (as many tend to routinely do when presented with real words). Consequently, the presentation of this subtest will tease out which students have good letter/sound correspondence abilities as well as solid orthographic, morphological and phonological awareness skills and which ones only memorized sight words and are now having difficulty decoding unfamiliar words as a result.

11. The Reading Fluency (RF) subtest (description above) requires students to efficiently read facts which make up simple stories fluently and correctly. Here are the key to attaining an average score is accuracy and automaticity. In contrast to the previous subtest, the words are now presented in meaningful simple syntactic contexts.

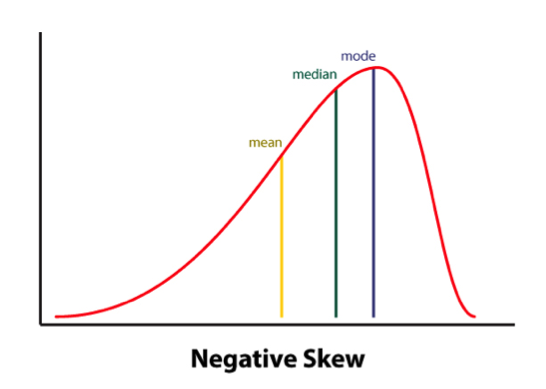

It is important to note that the Reading Fluency subtest of the TILLS has a negatively skewed distribution. As per authors, “a large number of typically developing students do extremely well on this subtest and a much smaller number of students do quite poorly.”

Thus, “the mean is to the left of the mode” (see publisher’s image below). This is why a student could earn an average standard score (near the mean) and a low percentile rank when true percentiles are used rather than NCE percentiles (Normal Curve Equivalent).

Consequently under certain conditions (See HERE) the percentile rank (vs. the NCE percentile) will be a more accurate representation of the student’s ability on this subtest.

Indeed, due to the reduced complexity of the presented words some students (especially younger elementary aged) may obtain average scores and still present with serious reading fluency deficits.

I frequently see that in students with average IQ and go to long-term memory, who by second and third grades have managed to memorize an admirable number of sight words due to which their deficits in the areas of reading appeared to be minimized. Recommendation: If you suspect that your student belongs to the above category I highly recommend supplementing this subtest with an informal measure of reading fluency. This can be done by presenting to the student a grade level text (I find science and social studies texts particularly useful for this purpose) and asking them to read several paragraphs from it (see HERE and/or HERE).

As the students are reading I calculate their reading fluency by counting the number of words they read per minute. I find it very useful as it allows me to better understand their reading profile (e.g, fast/inaccurate reader, slow/inaccurate reader, slow accurate reader, fast/accurate reader). As the student is reading I note their pauses, misreadings, word-attack skills and the like. Then, I write a summary comparing the students reading fluency on both standardized and informal assessment measures in order to document students strengths and limitations.

12. The Written Expression (WE) subtest (description above) needs to be administered to the students immediately after the administration of the Reading Fluency (RF) subtest because the student is expected to integrate a series of facts presented in the RF subtest into their writing sample. There are 4 stories in total for the 4 different age groups.

The examiner needs to show the student a different story which integrates simple facts into a coherent narrative. After the examiner reads that simple story to the students s/he is expected to tell the students that the story is okay, but “sounds kind of “choppy.” They then need to show the student an example of how they could put the facts together in a way that sounds more interesting and less choppy by combining sentences (see below). Finally, the examiner will ask the students to rewrite the story presented to them in a similar manner (e.g, “less choppy and more interesting.”)

After the student finishes his/her story, the examiner will analyze it and generate the following scores: a discourse score, a sentence score, and a word score. Detailed instructions as well as the Examiner’s Practice Workbook are provided to assist with scoring as it takes a bit of training as well as trial and error to complete it, especially if the examiners are not familiar with certain procedures (e.g., calculating T-units).

Full disclosure: Because the above subtest is still essentially sentence combining, I have only used this subtest a handful of times with my students. Typically when I’ve used it in the past, most of my students fell in two categories: those who failed it completely by either copying text word for word, failing to generate any written output etc. or those who passed it with flying colors but still presented with notable written output deficits. Consequently, I’ve replaced Written Expression subtest administration with the administration of written standardized tests, which I supplement with an informal grade level expository, persuasive, or narrative writing samples.

Having said that many clinicians may not have the access to other standardized written assessments, or lack the time to administer entire standardized written measures (which may frequently take between 60 to 90 minutes of administration time). Consequently, in the absence of other standardized writing assessments, this subtest can be effectively used to gauge the student’s basic writing abilities, and if needed effectively supplemented by informal writing measures (mentioned above).

13. The Social Communication (SC) subtest (description above) assesses the students’ ability to understand vocabulary associated with communicative intentions in social situations. It requires students to comprehend how people with certain characteristics might respond in social situations by formulating responses which fit the social contexts of those situations. Essentially students become actors who need to act out particular scenes while viewing select words presented to them.

Full disclosure: Similar to my infrequent administration of the Written Expression subtest, I have also administered this subtest very infrequently to students. Here is why.

I am an SLP who works full-time in a psychiatric hospital with children diagnosed with significant psychiatric impairments and concomitant language and literacy deficits. As a result, a significant portion of my job involves comprehensive social communication assessments to catalog my students’ significant deficits in this area. Yet, past administration of this subtest showed me that number of my students can pass this subtest quite easily despite presenting with notable and easily evidenced social communication deficits. Consequently, I prefer the administration of comprehensive social communication testing when working with children in my hospital based program or in my private practice, where I perform independent comprehensive evaluations of language and literacy (IEEs).

Again, as I’ve previously mentioned many clinicians may not have the access to other standardized social communication assessments, or lack the time to administer entire standardized written measures. Consequently, in the absence of other social communication assessments, this subtest can be used to get a baseline of the student’s basic social communication abilities, and then be supplemented with informal social communication measures such as the Informal Social Thinking Dynamic Assessment Protocol (ISTDAP) or observational social pragmatic checklists.

14. The Digit Span Forward (DSF) subtest (description above) is a relatively isolated measure of short term and verbal working memory ( it minimizes demands on other aspects of language such as syntax or vocabulary).

15. The Digit Span Backward (DSB) subtest (description above) assesses the student’s working memory and requires the student to mentally manipulate the presented stimuli in reverse order. It allows examiner to observe the strategies (e.g. verbal rehearsal, visual imagery, etc.) the students are using to aid themselves in the process. Please note that the Digit Span Forward subtest must be administered immediately before the administration of this subtest.

SLPs who have used tests such as the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5 (CELF-5) or the Test of Auditory Processing Skills – Third Edition (TAPS-3) should be highly familiar with both subtests as they are fairly standard measures of certain aspects of memory across the board.

To continue, in addition to the presence of subtests which assess the students literacy abilities, the TILLS also possesses a number of interesting features.

For starters, the TILLS Easy Score, which allows the examiners to use their scoring online. It is incredibly easy and effective. After clicking on the link and filling out the preliminary demographic information, all the examiner needs to do is to plug in this subtest raw scores, the system does the rest. After the raw scores are plugged in, the system will generate a PDF document with all the data which includes (but is not limited to) standard scores, percentile ranks, as well as a variety of composite and core scores. The examiner can then save the PDF on their device (laptop, PC, tablet etc.) for further analysis.

The there is the quadrant model. According to the TILLS sampler (HERE) “it allows the examiners to assess and compare students’ language-literacy skills at the sound/word level and the sentence/ discourse level across the four oral and written modalities—listening, speaking, reading, and writing” and then create “meaningful pro files of oral and written language skills that will help you understand the strengths and needs of individual students and communicate about them in a meaningful way with teachers, parents, and students. (pg. 21)”

Then there is the Student Language Scale (SLS) which is a one page checklist parents, teachers (and even students) can fill out to informally identify language and literacy based strengths and weaknesses. It allows for meaningful input from multiple sources regarding the students performance (as per IDEA 2004) and can be used not just with TILLS but with other tests or in even isolation (as per developers).

Furthermore according to the developers, because the normative sample included several special needs populations, the TILLS can be used with students diagnosed with ASD, deaf or hard of hearing (see caveat), as well as intellectual disabilities (as long as they are functioning age 6 and above developmentally).

According to the developers the TILLS is aligned with Common Core Standards and can be administered as frequently as two times a year for progress monitoring (min of 6 mos post 1st administration).

With respect to bilingualism examiners can use it with caution with simultaneous English learners but not with sequential English learners (see further explanations HERE). Translations of TILLS are definitely not allowed as they will undermine test validity and reliability.

So there you have it these are just some of my very few impressions regarding this test. Now to some of you may notice that I spend a significant amount of time pointing out some of the tests limitations. However, it is very important to note that we have research that indicates that there is no such thing as a “perfect standardized test” (see HERE for more information). All standardized tests have their limitations.

Having said that, I think that TILLS is a PHENOMENAL addition to the standardized testing market, as it TRULY appears to assess not just language but also literacy abilities of the students on our caseloads.

That’s all from me; however, before signing off I’d like to provide you with more resources and information, which can be reviewed in reference to TILLS. For starters, take a look at Brookes Publishing TILLS resources. These include (but are not limited to) TILLS FAQ, TILLS Easy-Score, TILLS Correction Document, as well as 3 FREE TILLS Webinars. There’s also a Facebook Page dedicated exclusively to TILLS updates (HERE).

But that’s not all. Dr. Nelson and her colleagues have been tirelessly lecturing about the TILLS for a number of years, and many of their past lectures and presentations are available on the ASHA website as well as on the web (e.g., HERE, HERE, HERE, etc). Take a look at them as they contain far more in-depth information regarding the development and implementation of this groundbreaking assessment.

To access TILLS fully-editable template, click HERE

Disclaimer: I did not receive a complimentary copy of this assessment for review nor have I received any encouragement or compensation from either Brookes Publishing or any of the TILLS developers to write it. All images of this test are direct property of Brookes Publishing (when clicked on all the images direct the user to the Brookes Publishing website) and were used in this post for illustrative purposes only.

References:

Leclercq A, Maillart C, Majerus S. (2013) Nonword repetition problems in children with SLI: A deficit in accessing long-term linguistic representations? Topics in Language Disorders. 33 (3) 238-254.

Related Posts:

- Components of Comprehensive Dyslexia Testing: Part I- Introduction and Language Testing

- Part II: Components of Comprehensive Dyslexia Testing – Phonological Awareness and Word Fluency Assessment

- Part III: Components of Comprehensive Dyslexia Testing – Reading Fluency and Reading Comprehension

- Part IV: Components of Comprehensive Dyslexia Testing – Writing and Spelling

- Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know

- Why (C) APD Diagnosis is NOT Valid!

- What Are Speech Pathologists To Do If the (C)APD Diagnosis is NOT Valid?

- What do Auditory Memory Deficits Indicate in the Presence of Average General Language Scores?

- Why Are My Child’s Test Scores Dropping?

- Comprehensive Assessment of Adolescents with Suspected Language and Literacy Disorders

If It’s NOT CAPD Then Where do SLPs Go From There?

In July 2015 I wrote a blog post entitled: “Why (C) APD Diagnosis is NOT Valid!” citing the latest research literature to explain that the controversial diagnosis of (C)APD tends to

In July 2015 I wrote a blog post entitled: “Why (C) APD Diagnosis is NOT Valid!” citing the latest research literature to explain that the controversial diagnosis of (C)APD tends to

a) detract from understanding that the child presents with legitimate language based deficits in the areas of comprehension, expression, social communication and literacy development

b) may result in the above deficits not getting adequately addressed due to the provision of controversial APD treatments

To CLARIFY, I was NOT trying to disprove that the processing deficits exhibited by the children diagnosed with “(C)APD” were not REAL. Rather I was trying to point out that these processing deficits are of neurolinguistic origin and as such need to be addressed from a linguistic rather than ‘auditory’ standpoint.

In other words, if one carefully analyzes the child’s so-called processing issues, one will quickly realize that those issues are not related to the processing of auditory input (auditory domain) since the child is not processing tones, hoots, or clicks, etc. but rather has difficulty processing speech and language (linguistic domain). Continue reading If It’s NOT CAPD Then Where do SLPs Go From There?

Teaching Metalinguistic Vocabulary for Reading Success

In my therapy sessions I spend a significant amount of time improving literacy skills (reading, spelling, and writing) of language impaired students. In my work with these students I emphasize goals with a focus on phonics, phonological awareness, encoding (spelling) etc. However, what I have frequently observed in my sessions are significant gaps in the students’ foundational knowledge pertaining to the basics of sound production and letter recognition. Basic examples of these foundational deficiencies involve students not being able to fluently name the letters of the alphabet, understand the difference between vowels and consonants, or fluently engage in sound/letter correspondence tasks (e.g., name a letter and then quickly and accurately identify which sound it makes). Consequently, a significant portion of my sessions involves explicit instruction of the above concepts.

In my therapy sessions I spend a significant amount of time improving literacy skills (reading, spelling, and writing) of language impaired students. In my work with these students I emphasize goals with a focus on phonics, phonological awareness, encoding (spelling) etc. However, what I have frequently observed in my sessions are significant gaps in the students’ foundational knowledge pertaining to the basics of sound production and letter recognition. Basic examples of these foundational deficiencies involve students not being able to fluently name the letters of the alphabet, understand the difference between vowels and consonants, or fluently engage in sound/letter correspondence tasks (e.g., name a letter and then quickly and accurately identify which sound it makes). Consequently, a significant portion of my sessions involves explicit instruction of the above concepts.

This got me thinking regarding my students’ vocabulary knowledge in general. We, SLPs, spend a significant amount of time on explicit and systematic vocabulary instruction with our students because as compared to typically developing peers, they have immature and limited vocabulary knowledge. But do we teach our students the abstract vocabulary necessary for reading success? Do we explicitly teach them definitions of a letter, a word, a sentence? etc.

A number of my colleagues are skeptical. “Our students already have poor comprehension”, they tell me, “Why should we tax their memory with abstract words of little meaning to them?” And I agree with them of course, but up to a point.

I agree that our students have working memory and processing speed deficits as a result of which they have a much harder time learning and recalling new words.

However, I believe that not teaching them meanings of select words pertaining to language is a huge disservice to them. Here is why. To be a successful communicator, speaker, reader, and writer, individuals need to possess adequate metalinguistic skills.

In simple terms “metalinguistics” refers to the individual’s ability to actively think about, talk about, and manipulate language. Reading, writing, and spelling require active level awareness and thought about language. Students with poor metalinguistic skills have difficulty learning to read, write, and spell. They lack awareness that spoken words are made up of individual units of sound, which can be manipulated. They lack awareness that letters form words, words form phrases and sentences, and sentences form paragraphs. They may not understand that letters make sounds or that a word may consist of more letters than sounds (e.g., /ship/). The bottom line is that students with decreased metalinguistic skills cannot effectively use language to talk about concepts like sounds, letters, or words unless they are explicitly taught those abilities.

So I do! Furthermore, I can tell you that explicit instruction of metalinguistic vocabulary does significantly improve my students understanding of the tasks involved in obtaining literacy competence. Even my students with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities significantly benefit from understanding the meanings of: letters, words, sentences, etc.

So I do! Furthermore, I can tell you that explicit instruction of metalinguistic vocabulary does significantly improve my students understanding of the tasks involved in obtaining literacy competence. Even my students with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities significantly benefit from understanding the meanings of: letters, words, sentences, etc.

I even created a basic abstract vocabulary handout to facilitate my students comprehension of these words (FREE HERE). While by no means exhaustive, it is a decent starting point for teaching my students the vocabulary needed to improve their metalinguistic skills.

For older elementary aged students with average IQ, I only provide the words I want them to define, and then ask them to look up their meanings online via the usage of PC or an iPad. This turns of vocabulary activity into a critical thinking and an executive functions task.

Students need to figure out the appropriate search string needed to in order to locate the answer as well as which definition comes the closest to clearly and effectively defining the presented word. One of the things I really like about Google online dictionary, is that it provides multiple definitions of the same words along with word origins. As a result, it teaches students to carefully review and reflect upon their selected definition in order to determine its appropriateness.

A word of caution as though regarding using Kiddle, Google-powered search engine for children. While it’s great for locating child friendly images, it is not appropriate for locating abstract definition of words. To illustrate, when you type in the string search into Google, “what is the definition of a letter?” You will get several responses which will appropriately match some meanings of your query. However the same string search in Kiddle, will merely yield helpful tips on writing a letter as well as images of envelopes with stamps affixed to them.

A word of caution as though regarding using Kiddle, Google-powered search engine for children. While it’s great for locating child friendly images, it is not appropriate for locating abstract definition of words. To illustrate, when you type in the string search into Google, “what is the definition of a letter?” You will get several responses which will appropriately match some meanings of your query. However the same string search in Kiddle, will merely yield helpful tips on writing a letter as well as images of envelopes with stamps affixed to them.

In contrast to the above, I use a more structured vocabulary defining activities for younger elementary age students as well as students with intellectual impairments. I provide simple definitions of abstract words, attach images and examples to each definition as well as create cloze activities and several choices of answers in order to ensure my students’ comprehension of these words.

I find that this and other metalinguistic activities significantly improve my students comprehension of abstract words such as ‘communication’, ‘language’, as well as ‘literacy’. They cease being mere buzzwords, frequently heard yet consistently not understood. To my students these words begin to come to life, brim with meaning, and inspire numerous ‘aha’ moments.

Now that you’ve had a glimpse of my therapy sessions I’d love to have a glimpse of yours. What metalinguistic goals related to literacy are you targeting with your students? Comment below to let me know.

Parent Consultation Services

Today I’d like to officially introduce a new parent consultation service which I had originally initiated with a few out-of-state clients through my practice a few years ago.

Today I’d like to officially introduce a new parent consultation service which I had originally initiated with a few out-of-state clients through my practice a few years ago.

The idea for this service came after numerous parents contacted me and initiated dialogue via email and phone calls regarding the services/assessments needed for their monolingual/bilingual internationally/domestically adopted or biological children with complex communication needs. Here are some details about it.

Parent consultations is a service provided to clients who live outside Smart Speech Therapy LLC geographical area (e.g., non-new Jersey residents) who are interested in comprehensive specialized in-depth consultations and recommendations regarding what type of follow up speech language services they should be seeking/obtaining in their own geographical area for their children as well as what type of carryover activities they should be doing with their children at home.

Consultations are provided with the focus on the following specialization areas with a focus on comprehensive assessment and intervention recommendations:

- Language and Literacy

- Children with Social Communication (Pragmatic) Disorders

- Bilingual and Multicultural Children

- Post-institutionalized Internationally Adopted Children

- Children with Psychiatric and Emotional Disturbances

- Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

The initial consultation length of this service is 1 hour. Clients are asked to forward their child’s records prior to the consultation for review, fill out several relevant intakes and questionnaires, as well as record a short video (3-5 minutes). The instructions regarding video content will be provided to them following session payment.

Upon purchasing a consultation the client will be immediately emailed the necessary paperwork to fill out as well as potential dates and times for the consultation to take place. Afternoon, Evening and Weekend hours are available for the client’s convenience. In cases of emergencies consultations may be rescheduled at the client’s/Smart Speech Therapy’s mutual convenience.

Refunds are available during a 3 day grace period if a mutually convenient time could not be selected for the consultation. Please note that fees will not be refundable from the time the scheduled consultation begins.

Following the consultation the client has the option of requesting a written detailed consultation report at an additional cost, which is determined based on the therapist’s hourly rate. For further information click HERE. You can also call 917-916-7487 or email tatyana.elleseff@smartspeechtherapy.com if you wanted to find out whether this service is right for you.

Below is a past parent consultation testimonial.

International Adoption Consultation Parent Testimonial (11/11/13)

I found Tatyana and Smart Speech Therapy online while searching for information about internationally adopted kids and speech evaluations. We’d already taken our three year old son to a local SLP but were very unsatisfied with her opinion, and we just didn’t know where to turn. Upon finding the articles and blogs written by Tatyana, I felt like I’d finally found someone who understood the language learning process unique to adopted kids, and whose writings could also help me in my meetings with the local school system as I sought special education services for my son.

I could have never predicted then just how much Tatyana and Smart Speech Therapy would help us. I used the online contact form on her website to see if Tatyana could offer us any services or recommendations, even though we are in Virginia and far outside her typical service area. She offered us an in-depth phone consultation that was probably one of the most informative, supportive and helpful phone calls I’ve had in the eight months since adopting my son. Through a series of videos, questionnaires, and emails, she was better able to understand my son’s speech difficulties and background than any of the other sources I’d sought help from. She was able to explain to me, a lay person, exactly what was going on with our son’s speech, comprehension, and learning difficulties in a way that a) added urgency to our situation without causing us to panic, b) provided me with a ton of research-orientated information for our local school system to review, and c) validated all my concerns and gut instincts that had previously been brushed aside by other physicians and professionals who kept telling us to “wait and see”.

After our phone call, we contracted Tatyana to provide us with an in-depth consultation report that we are now using with our local school and child rehab center to get our son the help he needs. Without that report, I don’t think we would have had the access to these services or the backing we needed to get people to seriously listen to us. It’s a terrible place to be in when you think something might be wrong, but you’re not sure and no one around you is listening. Tatyana listened to us, but more importantly, she looked at our son as a specific kid with a specific past and specific needs. We were more than just a number or file to her – and we’ve never even actually met in person! The best move we’ve could’ve made was sending her that email that day. We are so appreciative.

Kristen, P. Charlottesville, VA

Creating A Learning Rich Environment for Language Delayed Preschoolers

Today I’m excited to introduce a new product: “Creating A Learning Rich Environment for Language Delayed Preschoolers“. This 40 page presentation provides suggestions to parents regarding how to facilitate further language development in language delayed/impaired preschoolers at home in conjunction with existing outpatient, school, or private practice based speech language services. It details implementation strategies as well as lists useful materials, books, and websites of interest.

Today I’m excited to introduce a new product: “Creating A Learning Rich Environment for Language Delayed Preschoolers“. This 40 page presentation provides suggestions to parents regarding how to facilitate further language development in language delayed/impaired preschoolers at home in conjunction with existing outpatient, school, or private practice based speech language services. It details implementation strategies as well as lists useful materials, books, and websites of interest.

It is intended to be of interest to both parents and speech language professionals (especially clinical fellows and graduates speech pathology students or any other SLPs switching populations) and not just during the summer months. SLPs can provide it to the parents of their cleints instead of creating their own materials. This will not only save a significant amount of time but also provide a concrete step-by-step outline which explains to the parents how to engage children in particular activities from bedtime book reading to story formulation with magnetic puzzles.

Product Content:

- The importance of daily routines

- The importance of following the child’s lead

- Strategies for expanding the child’s language

- Self-Talk

- Parallel Talk

- Expansions

- Extensions

- Questioning

- Use of Praise

- A Word About Rewards

- How to Begin

- How to Arrange the environment

- Who is directing the show?

- Strategies for facilitating attention

- Providing Reinforcement

- Core vocabulary for listening and expression

- A word on teaching vocabulary order

- Teaching Basic Concepts

- Let’s Sing and Dance

- Popular toys for young language impaired preschoolers (3-4 years old)

- Playsets

- The Versatility of Bingo (older preschoolers)

- Books, Books, Books

- Book reading can be an art form

- Using Specific Story Prompts

- Focus on Story Characters and Setting

- Story Sequencing

- More Complex Book Interactions

- Teaching vocabulary of feelings and emotions

- Select favorite authors perfect for Pre-K

- Finding Intervention Materials Online The Easy Way

- Free Arts and Crafts Activities Anyone?

- Helpful Resources

Are you a caregiver, an SLP or a related professional? DOES THIS SOUND LIKE SOMETHING YOU CAN USE? if so you can find it HERE in my online store.

Useful Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Assessment Checklist for Preschool Aged Children

- Creating Functional Therapy Plan

- Selecting Clinical Materials for Pediatric Therapy

- Language Processing Checklist for Preschool Children

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children

- Recognizing the Warning Signs of Social Emotional Difficulties in Language Impaired Toddlers and Preschoolers

- Executive Function Impairments in At-Risk Pediatric Populations

References:

Heath, S. B (1982) What no bedtime story means: Narrative skills at home and school. Language in Society, vol. 11 pp. 49-76.

Useful Websites:

http://www.beyondplay.com

http://www.superdairyboy.com/Toys/magnetic_playsets.html

http://www.educationaltoysplanet.com/

http://www.melissaanddoug.com/shop.phtml

http://www.dltk-cards.com/bingo/

http://bogglesworldesl.com/

http://www.childrensbooksforever.com/index.html

Have you Worked on Morphological Awareness Lately?

Last year an esteemed colleague, Dr. Roseberry-McKibbin posed this question in our Bilingual SLPs Facebook Group: “Is anyone working on morphological awareness in therapy with ELLs (English Language Learners) with language disorders?”

Last year an esteemed colleague, Dr. Roseberry-McKibbin posed this question in our Bilingual SLPs Facebook Group: “Is anyone working on morphological awareness in therapy with ELLs (English Language Learners) with language disorders?”

Her question got me thinking: “How much time do I spend on treating morphological awareness in therapy with monolingual and bilingual language disordered clients?” The answer did not make me happy!

So what is morphological awareness and why is it important to address when treating monolingual and bilingual language impaired students?

Morphemes are the smallest units of language that carry meaning. They can be free (stand alone words such as ‘fair’, ‘toy’, or ‘pretty’) or bound (containing prefixes and suffixes that change word meanings – ‘unfair’ or ‘prettier’).

Morphological awareness refers to a ‘‘conscious awareness of the morphemic structure of words and the ability to reflect on and manipulate that structure’’ (Carlisle, 1995, p. 194). Also referred to as “the study of word structure” (Carlisle, 2004), it is an ability to recognize, understand, and use affixes or word parts (prefixes, suffixes, etc) that “carry significance” when speaking as well as during reading tasks. It is a hugely important skill for building vocabulary, reading fluency and comprehension as well as spelling (Apel & Lawrence, 2011; Carlisle, 2000; Binder & Borecki, 2007; Green, 2009).

So why is teaching morphological awareness important? Let’s take a look at some research.

Goodwin and Ahn (2010) found morphological awareness instruction to be particularly effective for children with speech, language, and/or literacy deficits. After reviewing 22 studies Bowers et al. (2010) found the most lasting effect of morphological instruction was on readers in early elementary school who struggled with literacy.

Morphological awareness instruction mediates and facilitates vocabulary acquisition leading to improved reading comprehension abilities (Bowers & Kirby, 2010; Carlisle, 2003, 2010; Guo, Roehrig, & Williams, 2011; Tong, Deacon, Kirby, Cain, & Parilla, 2011).

Unfortunately as important morphological instruction is for vocabulary building, reading fluency, reading comprehension, and spelling, it is often overlooked during the school years until it’s way too late. For example, traditionally morphological instruction only beings in late middle school or high school but research actually found that in order to be effective one should actually begin teaching it as early as first grade (Apel & Lawrence, 2011).

So now that we know that we need to target morphological instruction very early in children with language deficits, let’s talk a little bit regarding how morphological awareness can be assessed in language impaired learners.

When it comes to standardized testing, both the Test of Language Development: Intermediate – Fourth Edition (TOLD-I:4) and the Test of Adolescent and Adult Language–Fourth Edition (TOAL-4) have subtests which assess morphology as well as word derivations. However if you do not own either of these tests you can easily create non-standardized tasks to assess morphological awareness.

Apel, Diehm, & Apel (2013) recommend multiple measures which include: phonological awareness tasks, word level reading tasks, as well as reading comprehension tasks.

Below are direct examples of tasks from their study:

One can test morphological awareness via production or decomposition tasks. In a production task a student is asked to supply a missing word, given the root morpheme (e.g., ‘‘Sing. He is a great _____.’’ Correct response: singer). A decomposition task asks the student to identify the correct root of a given derivation or inflection. (e.g., ‘‘Walker. How slow can she _____?’’ Correct response: walk).

Another way to test morphological awareness is through completing analogy tasks since it involves both decomposition and production components (provide a missing word based on the presented pattern—crawl: crawled:: fly: ______ (flew).

Still another way to test morphological awareness with older students is through deconstruction tasks: Tell me what ____ word means? How do you know? (The student must explain the meaning of individual morphemes).

Finding the affix: Does the word ______ have smaller parts?

So what are the components of effective morphological instruction you might ask?

Below is an example of a ‘Morphological Awareness Intervention With Kindergarteners and First and Second Grade Students From Low SES Homes’ performed by Apel & Diehm, 2013:

Here are more ways in which this can be accomplished with older children:

- Find the root word in a longer word

- Fix the affix (an additional element placed at the beginning or end of a root, stem, or word, or in the body of a word, to modify its meaning)

- Affixes at the beginning of words are called “prefixes”

- Affixes at the end of words are called “suffixes

- Word sorts to recognize word families based on morphology or orthography

- Explicit instruction of syllable types to recognize orthographical patterns

- Word manipulation through blending and segmenting morphemes to further solidify patterns

Now that you know about the importance of morphological awareness, will you be incorporating it into your speech language sessions? I’d love to know!

Until then, Happy Speeching!

References:

- Apel, K., & Diehm, E. (2013). Morphological awareness intervention with kindergarteners and first and second grade students from low SES homes: A small efficacy study. Journal of Learning Disabilities.

- Apel, K., & Lawrence, J. (2011). Contributions of morphological awareness skills to word-level reading and spelling in first-grade children with and without speech sound disorder. Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research, 54, 1312–1327.

- Apel, K., Brimo, D., Diehm, E., & Apel, L. (2013). Morphological awareness intervention with kindergarteners and first and second grade students from low SES homes: A feasibility study. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 44, 161-173.

- Binder, K. & Borecki, C. (2007). The use of phonological, orthographic, and contextualinformation during reading: a comparison of adults who are learning to read and skilled adult readers. Reading and Writing, 21, 843-858.

- Bowers, P.N., Kirby, J.R., Deacon, H.S. (2010). The effects of morphological instruction on literacy skills: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 80, 144-179.

- Carlisle, J. F. (1995). Morphological awareness and early reading achievement. In L. B. Feldman (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 189–209). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Carlisle, J. F. (2000). Awareness of the structure and meaning of morphologically complex words: Impact on reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal,12,169-190.

- Carlisle, J. F. (2004). Morphological processes that influence learning to read. In C. A. Stone, E. R. Silliman, B. J. Ehren, & K. Apel (Eds.), Handbook of language and literacy. NY: Guilford Press.

- Carlisle, J. F. (2010). An integrative review of the effects of instruction in morphological awareness on literacy achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(4), 464-487.

- Goodwin, A.P. & Ahn, S. (2010). Annals of Dyslexia, 60, 183-208.

- Green, L. (2009). Morphology and literacy: Getting our heads in the game. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in the schools, 40, 283-285.

- Green, L., & Wolter, J.A. (2011, November). Morphological Awareness Intervention: Techniques for Promoting Language and Literacy Success. A symposium presentation at the annual American Speech Language Hearing Association, San Diego, CA.

- Guo, Y., Roehrig, A. D., & Williams, R. S. (2011). The relation of morphological awareness and syntactic awareness to adults’ reading comprehension: Is vocabulary knowledge a mediating variable? Journal of Literacy Research, 43, 159-183.

- Tong, X., Deacon, S. H., Kirby, J. R., Cain, K., & Parrila, R. (2011). Morphological awareness: A key to understanding poor reading comprehension in English. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103 (3), 523-534.