In the past several years, due to an influx of adolescent students with language and learning difficulties on my caseload, I have begun to research in depth aspects of adolescent language development, assessment, and intervention.

In the past several years, due to an influx of adolescent students with language and learning difficulties on my caseload, I have begun to research in depth aspects of adolescent language development, assessment, and intervention.

While a number of standardized assessments are available to test various components of adolescent language from syntax and semantics to problem-solving and social communication, etc., in my experience with this age group, frequently, clinical assessments (vs. the standardized tests), do a far better job of teasing out language difficulties in adolescents.

Today I wanted to write about the importance of performing a clinical reading assessment as part of select* adolescent language and literacy evaluations.

There are a number of standardized tests on the market, which presently assess reading. However, not all of them by far are as functional as many clinicians would like them to be. To illustrate, one popular reading assessment is the Gray Oral Reading Tests-5 (GORT-5). It assesses the student’s rate, accuracy, fluency, and comprehension abilities. While it’s a useful test to possess in one’s assessment toolbox, it is not without its limitations. In my experience assessing adolescent students with literacy deficits, many can pass this test with average scores, yet still present with pervasive reading comprehension difficulties in the school setting. As such, as part of the assessment process, I like to administer clinical reading assessments to students who pass the standardized reading tests (e.g., GORT-5), in order to ensure that the student does not possess any reading deficits at the grade text level.

So how do I clinically assess the reading abilities of struggling adolescent learners?

First, I select a one-page long grade level/below grade-level text (for very impaired readers). I ask the student to read the text, and I time the first minute of their reading in order to analyze their oral reading fluency or words correctly read per minute (wcpm).

For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 5 – 7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling adolescent readers. In some cases using a below grade level text allows me to starkly illustrate the extent of the student’s reading difficulties. Below is an example of one of such a clinical reading assessments in action.

For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 5 – 7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling adolescent readers. In some cases using a below grade level text allows me to starkly illustrate the extent of the student’s reading difficulties. Below is an example of one of such a clinical reading assessments in action.

CLINICAL READING ASSESSMENT: 8th Grade Male

A clinical reading assessment was administered to TS, a 15-5-year-old male, on a supplementary basis in order to further analyze his reading abilities. Given the fact that TS was reported to present with grade-level reading difficulties, the examiner provided TS a 7th-grade text by Continental Press. TS was asked to read aloud the 7 paragraph long text, and then answer factual and inferential questions, summarize the presented information, define select context embedded vocabulary words as well as draw conclusions based on the presented text. (Please note that in order to protect the client’s privacy some portions of the below assessment questions and responses were changed to be deliberately vague).

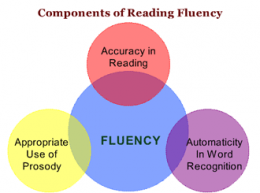

Reading Fluency: TS’s reading fluency (automaticity, prosody, accuracy and speed, expression, intonation, and phrasing) during the reading task was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody.

Reading Fluency: TS’s reading fluency (automaticity, prosody, accuracy and speed, expression, intonation, and phrasing) during the reading task was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody.

With respect to specific errors, TS was observed to occasionally add word fillers to text (e.g., and, a, etc.), change morphological endings of select words (e.g., read /elasticity/ as /elastic/, etc.) as well as substitute similar looking words (e.g., from/for; those/these, etc.) during reading. He occasionally placed stress on the first vs. second syllable in disyllabic words, which resulted in distorted word productions (e.g., products, residual, upward, etc.), as well as inserted extra words into text (e.g., read: “until pressure inside the earth starts to build again” as “until pressure inside the earth starts to build up again”). He also began reading a number of his sentences with false starts (e.g., started reading the word “drinking” as ‘drunk’, etc.) and as a result was observed to make a number of self-corrections during reading.

During reading, TS demonstrated adequate tracking movements for text scanning as well as use of context to aid his decoding. For example, TS was observed to read the phonetic spelling of select unfamiliar words in parenthesis (e.g., equilibrium) and then read them correctly in subsequent sentences. However, he exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies and did not always self-correct misread words; dispute the fact that they did not always make sense in the context of the read sentences.

TS’s oral reading rate during today’s reading was judged to be reduced for his age/grade levels. An average 8th grader is expected to have an oral reading rate between 145 and 160 words per minute. In contrast, TS was only able to read 114 words per minute. However, it is important to note that recent research on reading fluency has indicated that as early as by 4th grade reading faster than 90 wcpm will not generate increases in comprehension for struggling readers. Consequently, TS’s current reading rate of off 114 words per minute was judged to be adequate for reading purposes. Furthermore, given the fact that TS’s reading comprehension is already compromised at this rate (see below for further details) rather than making a recommendation to increase his reading rate further, it is instead recommended that intervention focuses on slowing TS’s rate via relevant strategies as well as improving his reading comprehension abilities. Strategies should focus on increasing his opportunities to learn domain knowledge via use of informational texts; purposeful selection of texts to promote knowledge acquisition and gain of expertise in different domains; teaching morphemic as well as semantic feature analyses (to expand upon already robust vocabulary), increasing discourse and critical thinking with respect to informational text, as well as use of graphic organizers to teach text structure and conceptual frameworks.

Verbal Text Summary: TS’s text summary following his reading was very abbreviated, simplified, and confusing. When asked: “What was this text about?” Rather than stating the main idea, TS nonspecifically provided several vague details and was unable to elaborate further. When asked: “Do you think you can summarize this story for me from beginning to the end?” TS produced the two disjointed statements, which did not adequately address the presented question When asked: “What is the main idea of this text.” TS vaguely responded: “Science,” which was the broad topic rather than the main idea of the story.

Text Vocabulary Comprehension:

Text Vocabulary Comprehension:

After that, TS was asked a number of questions regarding story vocabulary. The first word presented to him was “equilibrium”. When asked: “What does ‘equilibrium’ mean?” TS first incorrectly responded: “temperature”. Then when prompted: “Anything else?” TS correctly replied: “balance.” He was then asked to provide some examples of how nature leans towards equilibrium from the story. TS nonspecifically produced: “Ah, gravity.” When asked to explain how gravity contributes to the process of equilibrium TS again nonspecifically replied: “gravity is part of the planet”, and could not elaborate further. TS was then asked to define another word from the text provided to him in a sentence: “Scientists believe that this is residual heat remaining from the beginnings of the solar system.” What is the meaning of the word: “residual?” TS correctly identified: “remaining.” Then the examiner asked him to define the term found in the last paragraph of the text: “What is thermal equilibrium?” TS nonspecifically responded: “a balance of temperature”, and was unable to elaborate further.

Reading Comprehension (with/out text access):

TS was also asked to respond to a number of factual text questions without the benefit of visual support. However, he presented with significant difficulty recalling text details. TS was asked: When asked, “Why did this story mention ____? What did they have to do with ____?” TS responded nonspecifically, “______.” When prompted to tell more, TS produced a rambling response which did not adequately address the presented question. When asked: “Why did the text talk about bungee jumpers? How are they connected to it?” TS stated, “I am ah, not sure really.”

Finally, TS was provided with a brief worksheet which accompanied the text and asked to complete it given the benefit of written support. While TS’s performance on this task was better, he still achieved only 66% accuracy and was only able to answer 4 out of 6 questions correctly. On this task, TS presented with difficulty identifying the main idea of the third paragraph, even after being provided with multiple choice answers. He also presented with difficulty correctly responding to the question pertaining to the meaning of the last paragraph.

Impressions: Clinical below grade-level reading comprehension assessment reading revealed that TS presents with a number of reading related difficulties. TS’s reading fluency was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody. TS’s understanding as well as his verbal summary of the presented text was immature for his age and was characterized by impaired gestalt processing of information resulting in an ineffective and confusing summarization. While TS’s text-based vocabulary knowledge was deemed to be grossly adequate for his age, his reading comprehension abilities were judged to be impaired for his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve TS’s reading abilities. (See Impressions and Recommendations sections for further details).

Impressions: Clinical below grade-level reading comprehension assessment reading revealed that TS presents with a number of reading related difficulties. TS’s reading fluency was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody. TS’s understanding as well as his verbal summary of the presented text was immature for his age and was characterized by impaired gestalt processing of information resulting in an ineffective and confusing summarization. While TS’s text-based vocabulary knowledge was deemed to be grossly adequate for his age, his reading comprehension abilities were judged to be impaired for his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve TS’s reading abilities. (See Impressions and Recommendations sections for further details).

There you have it! This is just one of many different types of informal reading assessments, which I occasionally conduct with adolescents who attain average scores on reading fluency and reading comprehension tests such as the GORT-5 or the Test of Reading Comprehension -4 (TORC-4), but still present with pervasive reading difficulties working with grade level text.

You can find more information on the topic of adolescent assessments (including other comprehensive informal write-up examples) in this recently developed product entitled: Assessment of Adolescents with Language and Literacy Impairments in Speech Language Pathology currently available in my online store.

What about you? What type of informal tasks and materials are you using to assess your adolescent students’ reading abilities and why do you like using them?

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Adolescent Assessment Resources:

- Assessment of Adolescents with Language and Literacy Impairments in Speech Language Pathology

- Comprehensive Literacy Checklist For School-Aged Children

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents

[…] The above methods will reveal a true understanding of passage content. In contrast, multiple-choice questions and factual open-ended questions will tap into the student’s shallow knowledge of the passage and may result in an illusion that the student understands the passage, but are not adequate enough to ascertain true comprehension of passage content. […]

[…] years ago I wrote a post about how to perform clinical reading assessments of adolescent students. Today I am writing a follow-up post with a focus on the clinical reading assessment of […]

[…] Reading Assessment […]