Today it is my pleasure and privilege to interview 3 Australian lactation consultations: Lois Wattis, Renee Kam, and Pamela Douglas, the authors of a March 2017 article in the Breastfeeding Review: “Three experienced lactation consultants reflect upon the oral tie phenomenon” (which can be found HERE).

Today it is my pleasure and privilege to interview 3 Australian lactation consultations: Lois Wattis, Renee Kam, and Pamela Douglas, the authors of a March 2017 article in the Breastfeeding Review: “Three experienced lactation consultants reflect upon the oral tie phenomenon” (which can be found HERE).

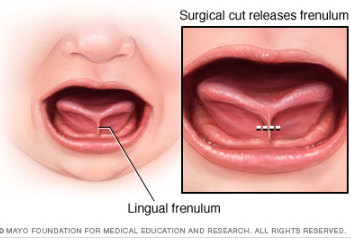

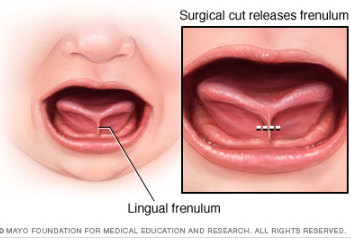

Tatyana Elleseff: Colleagues, as you very well know, the subject of ankyloglossia or tongue tie affecting breastfeeding and speech production has risen into significant prominence in the past several years. Numerous journal articles, blog posts, as well as social media forums have been discussing this phenomenon with rather conflicting recommendations. Many health professionals and parents are convinced that “releasing the tie” or performing either a frenotomy or frenectomy will lead to significant improvements in speech and feeding.

Presently, systematic reviews1-3 demonstrate there is insufficient evidence for the above. However, when many professionals including myself, cite reputable research explaining the lack of support of surgical intervention for tongue tie, there has been a pushback on the part of a number of other health professionals including lactation consultants, nurses, dentists, as well as speech-language pathologists stating that in their clinical experience surgical intervention does resolve issues with tongue tie as related to speech and feeding.

Presently, systematic reviews1-3 demonstrate there is insufficient evidence for the above. However, when many professionals including myself, cite reputable research explaining the lack of support of surgical intervention for tongue tie, there has been a pushback on the part of a number of other health professionals including lactation consultants, nurses, dentists, as well as speech-language pathologists stating that in their clinical experience surgical intervention does resolve issues with tongue tie as related to speech and feeding.

So today, given your 33 combined years of practice as lactation consultants I would love to ask your some questions regarding the tongue tie phenomena.

I would like to begin our discussion with a description of normal breastfeeding and what can interfere with it from an anatomical and physiological standpoint for mothers and babies.

Now, many of this blog’s readers already know that a tongue tie occurs when the connective tissue under the tongue known as a lingual frenulum restricts tongue movement to some degree and adversely affects its function. But many may not realize that children can present with a normal anatomical variant of “ties” which can be completely asymptomatic. Can you please address that?

Now, many of this blog’s readers already know that a tongue tie occurs when the connective tissue under the tongue known as a lingual frenulum restricts tongue movement to some degree and adversely affects its function. But many may not realize that children can present with a normal anatomical variant of “ties” which can be completely asymptomatic. Can you please address that?

Lois Wattis: “Normal” breastfeeding takes time and skill to achieve. The breastfeeding dyad is multifactorial, influenced by maternal breast and nipple anatomy combined with the infant’s facial and oral structures, all of which are highly variable. Mothers who have successfully breastfed the first baby may encounter problems with subsequent babies due to size (e.g., smaller, larger, etc.), be compromised by birth interventions or drugs during labor, or incur birth injuries – all of which can affect the initiation of breastfeeding and progression to a happy and comfortable feeding relationship. Unfortunately, the overview of each dyad’s story can be lost when tunnel vision of either health provider or parents regarding the baby’s oral anatomy is believed to be the chief influencer of breastfeeding success or failure.

Tatyana Elleseff: Colleagues, what do we know regarding the true prevalence of various ‘tongue ties’? Are there any studies of good quality?

Pamela Douglas: In a literature review in 2005, Hall and Renfrew acknowledged that the true prevalence of ankyloglossia remained unknown, though they estimated 3-4% of newborns.4

Pamela Douglas: In a literature review in 2005, Hall and Renfrew acknowledged that the true prevalence of ankyloglossia remained unknown, though they estimated 3-4% of newborns.4

After 2005, once the diagnosis of posterior tongue-tie (PTT) had been introduced,5, 6 attempts to quantify incidence of tongue-tie have remained of very poor quality, but estimates currently rest at between 4-10%.7

The problem is that there is a lack of definitional clarity concerning the diagnosis of PTT. Consequently, anterior or classic tongue tie CTT is now often conflated with PTT simply as ‘tongue-tie’ (TT).

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for clarifying it. In addition to the anterior and posterior tongue tie labels, many parents and professionals also frequently hear the terms lip tie and buccal ties. Is there’s reputable research behind these terms indicating that these ties can truly impact speech and feeding?

Pamela Douglas: Current definitions of ankyloglossia tend to confuse oral and tongue function (which is affected by multiple variables, and in particular by a fit and hold in breastfeeding) with structure (which is highly anatomically variable for both the tongue length and appearance and lingual and maxillary frenula).

For my own purposes, I define CTT as Type 1 and 2 on the Coryllos-Genna-Watson scale.8 In clinical practice, I also find it useful to rate the anterior membrane by the percentage of the undersurface of the tongue into which the membrane connects, applying the first two categories of the Griffiths Classification System.9

There is a wide spectrum of lingual frenula morphologies and elasticities, and deciding where to draw a line between a normal variant and CTT will depend on the clinical judgment concerning the infant’s capacity for pain-free efficient milk transfer. However, that means we need to have an approach to fit and hold that we are confident does optimize pain-free efficient milk transfer and at the moment, research shows that not only do the old ‘hands on’ approach to fit and hold not work, but that baby-led attachment is also not enough for many women. This is why at the Possums Clinic we’ve been working on developing an approach to fit and hold (gestalt breastfeeding) that builds on baby-led attachment but also integrates the findings of the latest ultrasound studies.

I personally don’t find the diagnoses of posterior tongue tie PTT and upper lip tie ULT helpful, and don’t use them. Lois, Renee and myself find that a wide spectrum of normal anatomic lingual and maxillary frenula variants are currently being misdiagnosed as a PTT and ULT, which has worried us and led Lois to initiate the article with Renee.

Tatyana Elleseff: Segueing from the above question: is there an established criterion based upon which a decision is made by relevant professionals to “release” the tie and if so can you explain how it’s determined?

Lois Wattis: When an anterior frenulum is attached at the tongue tip or nearby and is short enough to cause restriction of lift towards the palate, usually associated with extreme discomfort for the breastfeeding mother, I have no reservations about snipping it to release the tongue to enable optimal function for breastfeeding. If a simple frenotomy is going to assist the baby to breastfeed well it is worth doing, and as soon as possible. What I do encounter in my clinical practice are distressed and disempowered mothers whose baby has been labeled as having a posterior tongue tie and/or upper lip tie which is the cause of current and even future problems. Upon examination, the baby has completely normal oral anatomy and breastfeeding upskilling and confidence building of both mother and baby enables the dyad to go forward with strategies which address all elements of their unique story.

Lois Wattis: When an anterior frenulum is attached at the tongue tip or nearby and is short enough to cause restriction of lift towards the palate, usually associated with extreme discomfort for the breastfeeding mother, I have no reservations about snipping it to release the tongue to enable optimal function for breastfeeding. If a simple frenotomy is going to assist the baby to breastfeed well it is worth doing, and as soon as possible. What I do encounter in my clinical practice are distressed and disempowered mothers whose baby has been labeled as having a posterior tongue tie and/or upper lip tie which is the cause of current and even future problems. Upon examination, the baby has completely normal oral anatomy and breastfeeding upskilling and confidence building of both mother and baby enables the dyad to go forward with strategies which address all elements of their unique story.

Although the Hazelbaker Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function (ATLFF) is a pioneering contribution, bringing us our first systematized approach to examination of the infant’s tongue and oral connective tissues, it is unreliable as a tool for decision-making concerning frenotomy.10-12 In practice many of the item criteria are highly subjective. Although one study found moderate inter-rater reliability on the ATLFF’s structural items, the authors did not find inter-rater reliability on most of the functional items.13 In my clinical experience, there is no reliable correlation between what the tongue is observed to do during oral examinations and what occurs during breastfeeding, other than in the case of classic tongue-tie (excluding congenital craniofacial abnormalities from this discussion.

In my practice as a Lactation Consultant in an acute hospital setting I use a combination of the available assessment tools mainly for documentation purposes, however, the most important tools I use are my eyes and my ears. Observing the mother and baby physical combination and interactions, and suggesting adjustments where indicated to the positioning and attachment technique used (which Pam calls fit and hold) can very often resolve difficulties immediately – even if the baby also has an obvious frenulum under his/her tongue. Listening to the mother’s feedback, and observing the baby’s responses are primary indicators of whether further intervention is needed, or not. Watching how the baby achieves and retains the latch is key, then the examination of baby’s mouth to assess tongue mobility and appearance provide final information about whether baby’s ability to breastfeed comfortably is or is not being hindered by a restrictive lingual frenulum.

Tatyana Elleseff: So frenotomy is an incision (cut) of lingual frenum while frenectomy (complete removal) is an excision of lingual frenum. Both can be performed via various methods of “release”. What effects on breastfeeding have you seen with respect to healing?

Lois Wattis: The significant difference between both procedures involves the degree of invasiveness and level of pain experienced during and after the procedures, and the differing time it takes for the resumption and/or improvement in breastfeeding comfort and efficacy.

It is commonplace for a baby who has had a simple incision to breastfeed immediately after the procedure and exhibit no further signs of discomfort or oral aversion. Conversely, the baby who has had laser division(s) may breastfeed soon after the procedure while topical anesthetics are still working. However, many infants demonstrate discomfort, extreme pain responses and reluctance to feed for days or weeks following a laser treatment. Parents are warned to expect delays resuming feeding and the baby is usually also subjected to wound “stretches” for weeks following the laser treatments. Unfortunately, in my clinical practice I see many parents and babies who are very traumatized by this whole process, and in many cases, breastfeeding can be derailed either temporarily or permanently.

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you! This is highly relevant information for both health professionals and parents alike. I truly appreciate your clinical expertise on this topic. While we are on the topic of restrictive lingual frenulums can we discuss several recent articles published on surgical interventions for the above? For example (Ghaheri, Cole, Fausel, Chuop & Mace, 2016), recently published the result of their study which concluded that: “Surgical release of tongue-tie/lip-tie results in significant improvement in breastfeeding outcomes”. Can you elucidate upon the study design and its findings?

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you! This is highly relevant information for both health professionals and parents alike. I truly appreciate your clinical expertise on this topic. While we are on the topic of restrictive lingual frenulums can we discuss several recent articles published on surgical interventions for the above? For example (Ghaheri, Cole, Fausel, Chuop & Mace, 2016), recently published the result of their study which concluded that: “Surgical release of tongue-tie/lip-tie results in significant improvement in breastfeeding outcomes”. Can you elucidate upon the study design and its findings?

Pamela Douglas: Pre-post surveys, such as Ghaheri et al’s 2016 study, are notoriously methodologically weak and prone to interpretive bias.14

Renee Kam: Research about the efficacy of releasing ULTs to improve breastfeeding outcomes is seriously lacking. There is no reliable assessment tool for upper lip-tie and a lack of evidence to support the efficacy of a frenotomy of labial frenula in breastfed babies. The few studies which have included ULT release have either included very small numbers of babies having upper lip-tie releases or have included babies having a release upper lip ties and tongue ties at the same time, making it impossible to know if any improvements were due to the tongue-tie release, upper lip-tie release or both. Here, to answer your previous question, to date, no research has looked into the treatment of buccal ties for breastfeeding outcomes.

There are various classification scales for labial frenulums such as the Kotlow scale. The title of this scale is misleading as it contains the word ‘tie’. Hence it can give some people the incorrect assumption that a class III or IV labial frenulum is somehow a problem. What this scale actually shows is the normal range of insertion sites for a labial frenulum. And, in normal cases, the vast majority of babies’ labial frenulums insert low down on the upper gum (class III) or even wrap around it (class IV). It’s important to note that, for effective breastfeeding, the upper lip does not have to flange out in order to create a seal. It just has to rest in a neutral position — not flanged out, not tucked in.

Lois Wattis: I entirely agree with Renee’s view about the neutrality of the upper lip, including the labial frenulum, in relation to latch for breastfeeding. Even babies with asymmetrical facial features, cleft lips and other permanent and temporary anomalies only need to achieve a seal with the upper lip to breastfeed successfully.

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for that. In addition to studies on tongue tie revisions and breastfeeding outcomes, there has been an increase in studies, specifically Kotlow (2016) and Siegel (2016), which claimed that surgical intervention improves outcomes for acid reflux and aerophagia in babies”. Can you discuss these studies design and findings?

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for that. In addition to studies on tongue tie revisions and breastfeeding outcomes, there has been an increase in studies, specifically Kotlow (2016) and Siegel (2016), which claimed that surgical intervention improves outcomes for acid reflux and aerophagia in babies”. Can you discuss these studies design and findings?

Renee Kam: The AIR hypothesis has led to reflux being used as another reason to diagnose the oral anatomic abnormalities in infants in the presence of breastfeeding problems. More research with objective indicators and less vested interest is needed in this area. A thorough understanding of normal infant behavior and feeding problems which aren’t tie related are also imperative before any conclusions about AIR can be reached.

Tatyana Elleseff: One final question, colleagues are you aware of any studies which describe long-term outcomes of surgical interventions for tongue ties?

Pamela Douglas: The systematic reviews note that there is a lack of evidence demonstrating long-term outcomes of surgical interventions.

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for such informative discussion, colleagues.

There you have it, readers. Both research and clinical practice align to indicate that:

There you have it, readers. Both research and clinical practice align to indicate that:

- There’s significant normal variation when it comes to most anatomical structures including the frenulum

- Just because a child presents with restricted frenulum does not automatically imply adverse feeding as well as speech outcomes and immediately necessitates a tongue tie release

- When breastfeeding difficulties arise, in the presence of restricted frenulum, it is very important to involve an experienced lactation specialist who will perform a differential diagnosis in order to determine the source of the baby’s true breastfeeding difficulties

Now, I’d like to take a moment and address the myth of tongue ties affecting speech production, which continues to persist among speech-language pathologists despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

For that purpose, I will use excerpts from an excellent ASHA Leader December 2005 article written by an esteemed Dr. Kummer who is certainly well qualified to discuss this issue. According to Dr. Kummer, “there is no empirical evidence in the literature that ankyloglossia typically causes speech defects. On the contrary, several authors, even from decades ago, have disputed the belief that there is a strong causal relationship (Wallace, 1963; Block, 1968; Catlin & De Haan, 1971; Wright, 1995; Agarwal & Raina, 2003).”

Since many children with restricted frenulum do not have any speech production difficulties, Dr Kummer explains why that is the case by discussing the effect of tongue tip positioning for speech production.

Since many children with restricted frenulum do not have any speech production difficulties, Dr Kummer explains why that is the case by discussing the effect of tongue tip positioning for speech production.

“Lingual-alveolar sounds (t, d, n) are produced with the top of the tongue tip and therefore, they can be produced with very little tongue elevation or mobility.

The /s/ and /z/ sounds require the tongue tip to be elevated only slightly but can be produced with little distortion if the tip is down.

The most the tongue tip needs to elevate is to the alveolar ridge for the production of an /l/. However, this sound can actually be produced with the tongue tip down and the dorsum of the tongue up against the alveolar ridge. Even an /r/ sound can be produced with the tongue tip down as long as the back of the tongue is elevated on both sides.

The most the tongue needs to protrude is to the back of the maxillary incisors for the production of /th/. All of these sounds can usually be produced, even with significant tongue tip restriction. This can be tested by producing these sounds with the tongue tip pressed down or against the mandibular gingiva. This results in little, if any, distortion.” (Kummer, 2005, ASHA Leader)

In 2009, Dr. Sharynne McLeod, did research on electropalatography of speech sounds with adults. Her findings (below) which are coronal images of tongue positioning including bracing, lateral contact and groove formation for consonants support the above information provided by Dr. Kummer.

Once again research and clinical practice align to indicate that there’s insufficient evidence to indicate the effect of restricted frenulum on the production of speech sounds.

Finally, I would like to conclude this post with a list of links from recent systematic reviews summarizing the latest research on this topic.

Ankyloglossia/Tongue Tie Systematic Review Summaries to Date (2017):

- A small body of evidence suggests that frenotomy may be associated with mother reported improvements in breastfeeding, and potentially in nipple pain, but with small, short-term studies with inconsistent methodology, the strength of the evidence is low to insufficient.

- In an infant with tongue-tie and feeding difficulties, surgical release of the tongue-tie does not consistently improve infant feeding but is likely to improve maternal nipple pain. Further research is needed to clarify and confirm this effect.

- Data are currently insufficient for assessing the effects of frenotomy on nonbreastfeeding outcomes that may be associated with ankyloglossia

- Given the lack of good-quality studies and limitations in the measurement of outcomes, we considered the strength of the evidence for the effect of surgical interventions to improve speech and articulation to be insufficient.

- Large temporal increases and substantial spatial variations in ankyloglossia and frenotomy rates were observed that may indicate a diagnostic suspicion bias and increasing use of a potentially unnecessary surgical procedure among infants.

References

- Power R, Murphy J. Tongue-tie and frenotomy in infants with breastfeeding difficulties: achieving a balance. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2015;100:489-494.

- Francis DO, Krishnaswami S, McPheeters M. Treatment of ankyloglossia and breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):e1467-e1474.

- O’Shea JE, Foster JP, O’Donnell CPF, Breathnach D, Jacobs SE, Todd DA, et al. Frenotomy for tongue-tie in newborn infants (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (3):Art. No.:CD011065.

- Hall D, Renfrew M. Tongue tie. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90:1211-1215.

- Coryllos E, Watson Genna C, Salloum A. Congenital tongue-tie and its impact on breastfeeding. Breastfeeding: Best for Mother and Baby, American Academy of Pediatrics. 2004 Summer:1-6.

- Coryllos EV, Watson Genna C, LeVan Fram J. Minimally Invasive Treatment for Posterior Tongue-Tie (The Hidden Tongue-Tie). In: Watson Genna C, editor. Supporting Sucking Skills. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2013. p. 243-251.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Infant feeding guidelines: information for health workers. In: Government A, editor. 2012. p. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/n56.

- Watson Genna C, editor. Supporting sucking skills in breastfeeding infants. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2016.

- Griffiths DM. Do tongue ties affect breastfeeding? . Journal of Human Lactation. 2004;20:411.

- Ricke L, Baker N, Madlon-Kay D. Newborn tongue-tie: prevalence and effect on breastfeeding. Journal of American Board of Family Practice. 2005;8:1-8.

- Madlon-Kay D, Ricke L, Baker N, DeFor TA. Case series of 148 tongue-tied newborn babies evaluated with the assessment tool for lingual function. Midwifery. 2008;24:353-357.

- Ballard JL, Auer CE, Khoury JC. Ankyloglossia: assessment, incidence, and effect of frenuloplasty on the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e63.

- Amir L, James JP, Donath SM. Reliability of the Hazelbaker Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2006;1:3.

- Douglas PS. Conclusions of Ghaheri’s study that laser surgery for posterior tongue and lip ties improve breastfeeding are not substantiated. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2017;12(3):DOI: 10.1089/bfm.2017.0008.

Author Bios (in alphabetical order):

Dr. Pamela Douglas is the founder of a charitable organization, the Possums Clinic, a general practitioner since 1987, an IBCLC (1994-2004; 2012-Present) and researcher. She is an Associate Professor (Adjunct) with the Centre for Health Practice Innovation, Griffith University, and a Senior Lecturer with the Discipline of General Practice, The University of Queensland. Pam enjoys working clinically with families across the spectrum of challenges in early life, many complex (including breastfeeding difficulty) unsettled infant behaviors, reflux, allergies, tongue-tie/oral connective tissue problems, and gut problems. She is author of The discontented little baby book: all you need to know about feeds, sleep and crying (UQP) www.possumsonline.com; www.pameladouglas.com.au

Dr. Pamela Douglas is the founder of a charitable organization, the Possums Clinic, a general practitioner since 1987, an IBCLC (1994-2004; 2012-Present) and researcher. She is an Associate Professor (Adjunct) with the Centre for Health Practice Innovation, Griffith University, and a Senior Lecturer with the Discipline of General Practice, The University of Queensland. Pam enjoys working clinically with families across the spectrum of challenges in early life, many complex (including breastfeeding difficulty) unsettled infant behaviors, reflux, allergies, tongue-tie/oral connective tissue problems, and gut problems. She is author of The discontented little baby book: all you need to know about feeds, sleep and crying (UQP) www.possumsonline.com; www.pameladouglas.com.au

Renee Kam qualified with a Bachelor of Physiotherapy from the University of Melbourne in 2000. She then worked as a physiotherapist for 6 years, predominantly in the areas of women’s health, pediatric and musculoskeletal physiotherapy. She became an Australian Breastfeeding Association Breastfeeding (ABA) counselor in 2010 and obtained the credential of International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) in 2012. In 2013, Renee’s book, The Newborn Baby Manual, was published which covers the topics that Renee is passionate about; breastfeeding, baby sleep and baby behavior. These days, Renee spends most of her time being a mother to her two young daughters, writing breastfeeding content for BellyBelly.com.au, fulfilling her role as national breastfeeding information manager with ABA and working as an IBCLC in private practice and at a private hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

Renee Kam qualified with a Bachelor of Physiotherapy from the University of Melbourne in 2000. She then worked as a physiotherapist for 6 years, predominantly in the areas of women’s health, pediatric and musculoskeletal physiotherapy. She became an Australian Breastfeeding Association Breastfeeding (ABA) counselor in 2010 and obtained the credential of International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) in 2012. In 2013, Renee’s book, The Newborn Baby Manual, was published which covers the topics that Renee is passionate about; breastfeeding, baby sleep and baby behavior. These days, Renee spends most of her time being a mother to her two young daughters, writing breastfeeding content for BellyBelly.com.au, fulfilling her role as national breastfeeding information manager with ABA and working as an IBCLC in private practice and at a private hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

Lois Wattis is a Registered Nurse/Midwife, International Board Certified Lactation Consultant and Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives. Working in both hospital and community settings, Lois has enhanced her midwifery skills and expertise by providing women-centred care to thousands of mothers and babies, including more than 50 women who chose to give birth at home. Lois’ qualifications include Bachelor of Nursing Degree (Edith Cowan University, Perth WA), Post Graduate Diploma in Clinical Nursing, Midwifery (Curtin University, Perth WA), accreditation as Independent Practising Midwife by the Australian College of Midwives in 2002 and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant in 2004. Lois was inducted as a Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives (FACM) in 2005 in recognition of her services to women and midwifery in Australia. Lois has authored numerous articles which have been published internationally in parenting and midwifery journals, and shares her broad experience via her creations “New Baby 101” book, smartphone App, on-line videos and Facebook page. www.newbaby101.com.au Lois has worked for the past 10 years in Qld, Australia in a dedicated Lactation Consultant role as well as in private practice www.birthjourney.com

Lois Wattis is a Registered Nurse/Midwife, International Board Certified Lactation Consultant and Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives. Working in both hospital and community settings, Lois has enhanced her midwifery skills and expertise by providing women-centred care to thousands of mothers and babies, including more than 50 women who chose to give birth at home. Lois’ qualifications include Bachelor of Nursing Degree (Edith Cowan University, Perth WA), Post Graduate Diploma in Clinical Nursing, Midwifery (Curtin University, Perth WA), accreditation as Independent Practising Midwife by the Australian College of Midwives in 2002 and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant in 2004. Lois was inducted as a Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives (FACM) in 2005 in recognition of her services to women and midwifery in Australia. Lois has authored numerous articles which have been published internationally in parenting and midwifery journals, and shares her broad experience via her creations “New Baby 101” book, smartphone App, on-line videos and Facebook page. www.newbaby101.com.au Lois has worked for the past 10 years in Qld, Australia in a dedicated Lactation Consultant role as well as in private practice www.birthjourney.com

Several days ago I had a conversation with the Associate Director of Continuing Education at ASHA regarding my significant concerns about the content and quality of some of ASHA approved continuing education courses. For many months before that, numerous discussions took place in a variety of major SLP related Facebook groups, pertaining to the non-EBP content of some of ASHA approved provider coursework, many of which was blatantly pseudoscientific in nature.

Several days ago I had a conversation with the Associate Director of Continuing Education at ASHA regarding my significant concerns about the content and quality of some of ASHA approved continuing education courses. For many months before that, numerous discussions took place in a variety of major SLP related Facebook groups, pertaining to the non-EBP content of some of ASHA approved provider coursework, many of which was blatantly pseudoscientific in nature. Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

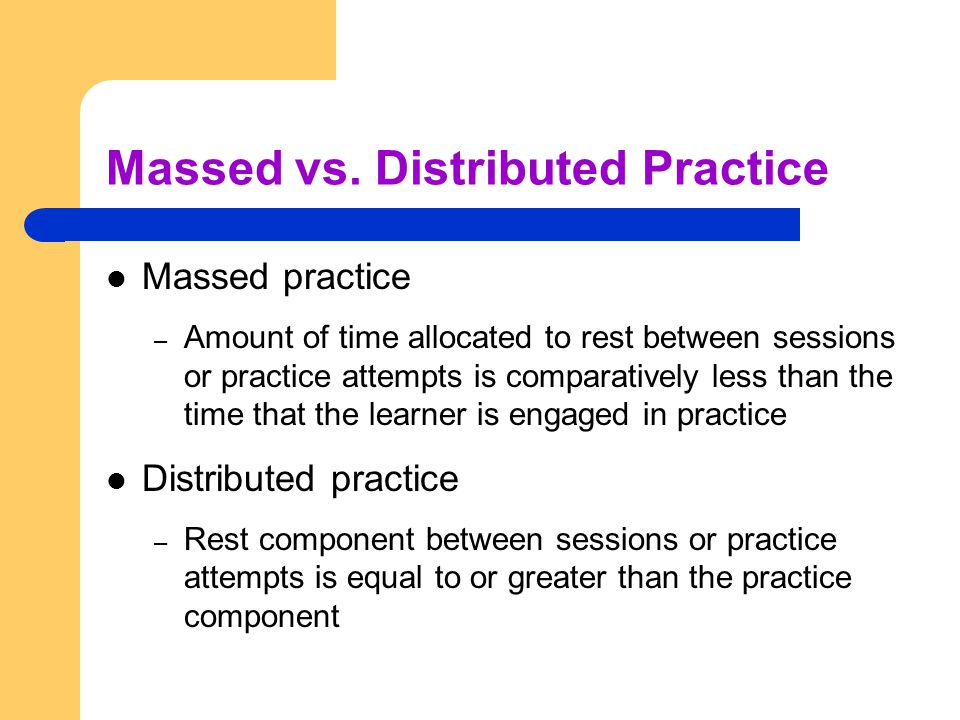

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute. After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than

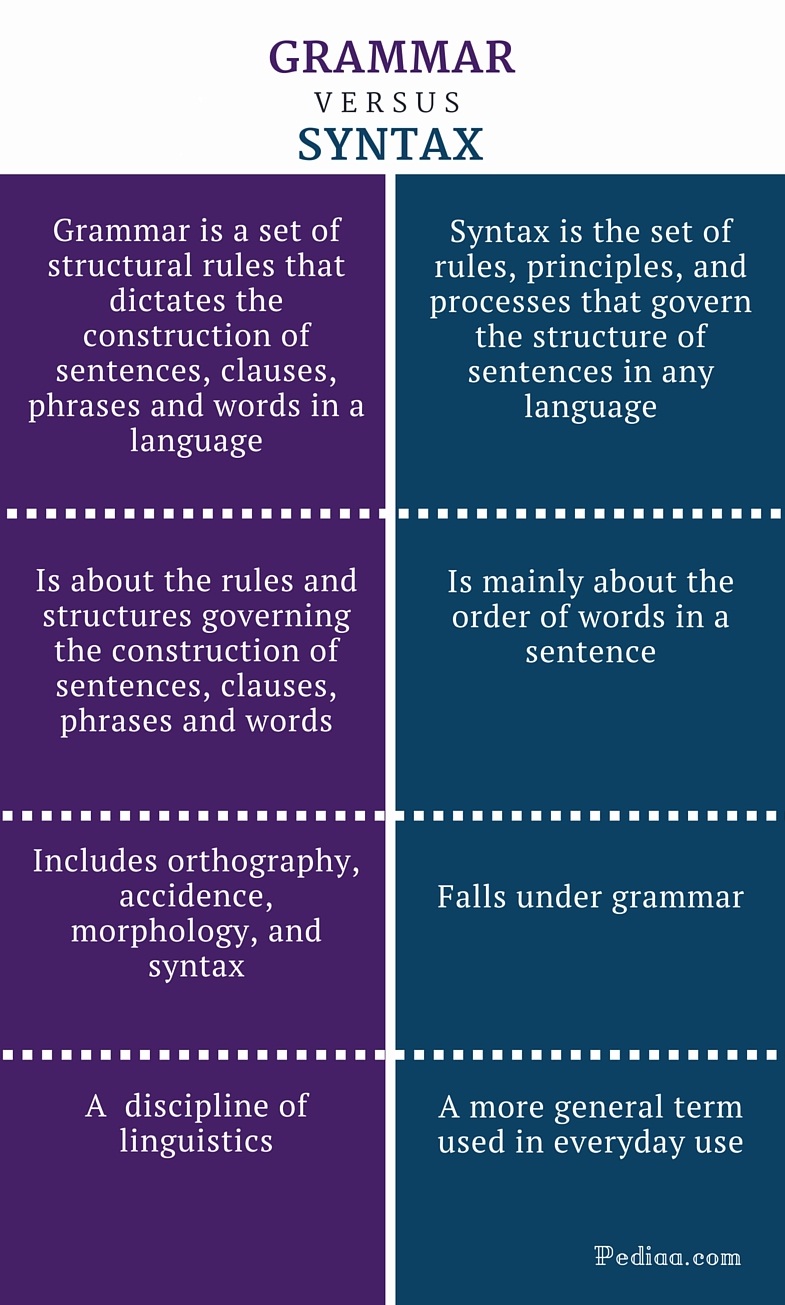

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by  Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements). There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same  Assessment of motor speech disorders in young children requires solid knowledge and expertise. That is because CAS has a number of overlapping symptoms with other speech sound disorders (e.g., severe phonological disorder, dysarthria, etc). Furthermore, symptoms which may initially appear as CAS may change during the course of intervention by the time the child is older (e.g., 3 years of age) which is why diagnosing toddlers under 3 years of age is very problematic and the use of “suspected” or “working” diagnosis is recommended (Davis & Velleman, 2000) in order to avoid misdiagnosis. Finally, the diagnosis of CAS is also problematic due to the fact that there are still to this day no valid or reliable standardized assessments sensitive to CAS detection (McCauley & Strand, 2008).

Assessment of motor speech disorders in young children requires solid knowledge and expertise. That is because CAS has a number of overlapping symptoms with other speech sound disorders (e.g., severe phonological disorder, dysarthria, etc). Furthermore, symptoms which may initially appear as CAS may change during the course of intervention by the time the child is older (e.g., 3 years of age) which is why diagnosing toddlers under 3 years of age is very problematic and the use of “suspected” or “working” diagnosis is recommended (Davis & Velleman, 2000) in order to avoid misdiagnosis. Finally, the diagnosis of CAS is also problematic due to the fact that there are still to this day no valid or reliable standardized assessments sensitive to CAS detection (McCauley & Strand, 2008). Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion.

Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion. TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output.

TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output. I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made.

I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made. *For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the

*For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the  Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of

Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of  Today it is my pleasure and privilege to interview 3 Australian lactation consultations: Lois Wattis, Renee Kam, and Pamela Douglas, the authors of a March 2017 article in the Breastfeeding Review: “Three experienced lactation consultants reflect upon the oral tie phenomenon” (which can be found

Today it is my pleasure and privilege to interview 3 Australian lactation consultations: Lois Wattis, Renee Kam, and Pamela Douglas, the authors of a March 2017 article in the Breastfeeding Review: “Three experienced lactation consultants reflect upon the oral tie phenomenon” (which can be found  Presently, systematic reviews1-3 demonstrate there is insufficient evidence for the above. However, when many professionals including myself, cite reputable research explaining the lack of support of surgical intervention for tongue tie, there has been a pushback on the part of a number of other health professionals including lactation consultants, nurses, dentists, as well as speech-language pathologists stating that in their clinical experience surgical intervention does resolve issues with tongue tie as related to speech and feeding.

Presently, systematic reviews1-3 demonstrate there is insufficient evidence for the above. However, when many professionals including myself, cite reputable research explaining the lack of support of surgical intervention for tongue tie, there has been a pushback on the part of a number of other health professionals including lactation consultants, nurses, dentists, as well as speech-language pathologists stating that in their clinical experience surgical intervention does resolve issues with tongue tie as related to speech and feeding.

Pamela Douglas:

Pamela Douglas:

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you! This is highly relevant information for both health professionals and parents alike. I truly appreciate your clinical expertise on this topic. While we are on the topic of restrictive lingual frenulums can we discuss several recent articles published on surgical interventions for the above? For example (Ghaheri, Cole, Fausel, Chuop & Mace, 2016), recently published the result of their study which concluded that: “Surgical release of tongue-tie/lip-tie results in significant improvement in breastfeeding outcomes”. Can you elucidate upon the study design and its findings?

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you! This is highly relevant information for both health professionals and parents alike. I truly appreciate your clinical expertise on this topic. While we are on the topic of restrictive lingual frenulums can we discuss several recent articles published on surgical interventions for the above? For example (Ghaheri, Cole, Fausel, Chuop & Mace, 2016), recently published the result of their study which concluded that: “Surgical release of tongue-tie/lip-tie results in significant improvement in breastfeeding outcomes”. Can you elucidate upon the study design and its findings? Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for that. In addition to studies on tongue tie revisions and breastfeeding outcomes, there has been an increase in studies, specifically Kotlow (2016) and Siegel (2016), which claimed that surgical intervention improves outcomes for acid reflux and aerophagia in babies”. Can you discuss these studies design and findings?

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for that. In addition to studies on tongue tie revisions and breastfeeding outcomes, there has been an increase in studies, specifically Kotlow (2016) and Siegel (2016), which claimed that surgical intervention improves outcomes for acid reflux and aerophagia in babies”. Can you discuss these studies design and findings? There you have it, readers. Both research and clinical practice align to indicate that:

There you have it, readers. Both research and clinical practice align to indicate that: Since many children with restricted frenulum do not have any speech production difficulties, Dr Kummer explains why that is the case by discussing

Since many children with restricted frenulum do not have any speech production difficulties, Dr Kummer explains why that is the case by discussing

I’ve been meaning to write this post for some time and have finally decided to do it now due to an increased prevalence of “non-traditional” treatment options available to parents of language impaired children.

I’ve been meaning to write this post for some time and have finally decided to do it now due to an increased prevalence of “non-traditional” treatment options available to parents of language impaired children.

There you have it: that’s what the harm is! The toll of these quack practices can be very significant and can go far beyond the financial. So the next time someone utters the statement: “What’s the Harm in That?” consider the above information in order to make the informed decisions regarding the treatment for the most vulnerable parties involved: the children in your care!

There you have it: that’s what the harm is! The toll of these quack practices can be very significant and can go far beyond the financial. So the next time someone utters the statement: “What’s the Harm in That?” consider the above information in order to make the informed decisions regarding the treatment for the most vulnerable parties involved: the children in your care!