![]() Several years ago I began blogging on the subject of independent assessments in speech pathology. First, I wrote a post entitled “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“, in which I used 4 different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Then I wrote about: “What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?” in order to elucidate on what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading Neuropsychological or Language/Literacy: Which Assessment is Right for My Child?

Several years ago I began blogging on the subject of independent assessments in speech pathology. First, I wrote a post entitled “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“, in which I used 4 different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Then I wrote about: “What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?” in order to elucidate on what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading Neuropsychological or Language/Literacy: Which Assessment is Right for My Child?

Category: Developmental Disabilities

Dear SLPs, Try Asking This Instead

I frequently see numerous posts on Facebook that ask group members, “What are your activities/goals for a particular age group (e.g., preschool, middle school, high school, etc.) or a particular disorder (e.g., Down Syndrome)? After seeing these posts appear over and over again in a variety of groups, I decided to write my own post on this topic, explaining why asking such broad questions will not result in optimal therapeutic interventions for the clients in question. Continue reading Dear SLPs, Try Asking This Instead

I frequently see numerous posts on Facebook that ask group members, “What are your activities/goals for a particular age group (e.g., preschool, middle school, high school, etc.) or a particular disorder (e.g., Down Syndrome)? After seeing these posts appear over and over again in a variety of groups, I decided to write my own post on this topic, explaining why asking such broad questions will not result in optimal therapeutic interventions for the clients in question. Continue reading Dear SLPs, Try Asking This Instead

How Early can “Dyslexia” be Diagnosed in Children?

In recent years there has been a substantial rise in awareness pertaining to reading disorders in young school-aged children. Consequently, more and more parents and professionals are asking questions regarding how early can “dyslexia” be diagnosed in children.

In order to adequately answer this question, it is important to understand the trajectory of development of literacy disorders in children. Continue reading How Early can “Dyslexia” be Diagnosed in Children?

Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

Making Our Interventions Count or What’s Research Got To Do With It?

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “What’s Memes Got To Do With It?” which summarized key points of Dr. Alan G. Kamhi’s 2004 article: “A Meme’s Eye View of Speech-Language Pathology“. It delved into answering the following question: “Why do some terms, labels, ideas, and constructs [in our field] prevail whereas others fail to gain acceptance?”.

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “What’s Memes Got To Do With It?” which summarized key points of Dr. Alan G. Kamhi’s 2004 article: “A Meme’s Eye View of Speech-Language Pathology“. It delved into answering the following question: “Why do some terms, labels, ideas, and constructs [in our field] prevail whereas others fail to gain acceptance?”.

Today I would like to reference another article by Dr. Kamhi written in 2014, entitled “Improving Clinical Practices for Children With Language and Learning Disorders“.

This article was written to address the gaps between research and clinical practice with respect to the implementation of EBP for intervention purposes.

Dr. Kamhi begins the article by posing 10 True or False questions for his readers:

- Learning is easier than generalization.

- Instruction that is constant and predictable is more effective than instruction that varies the conditions of learning and practice.

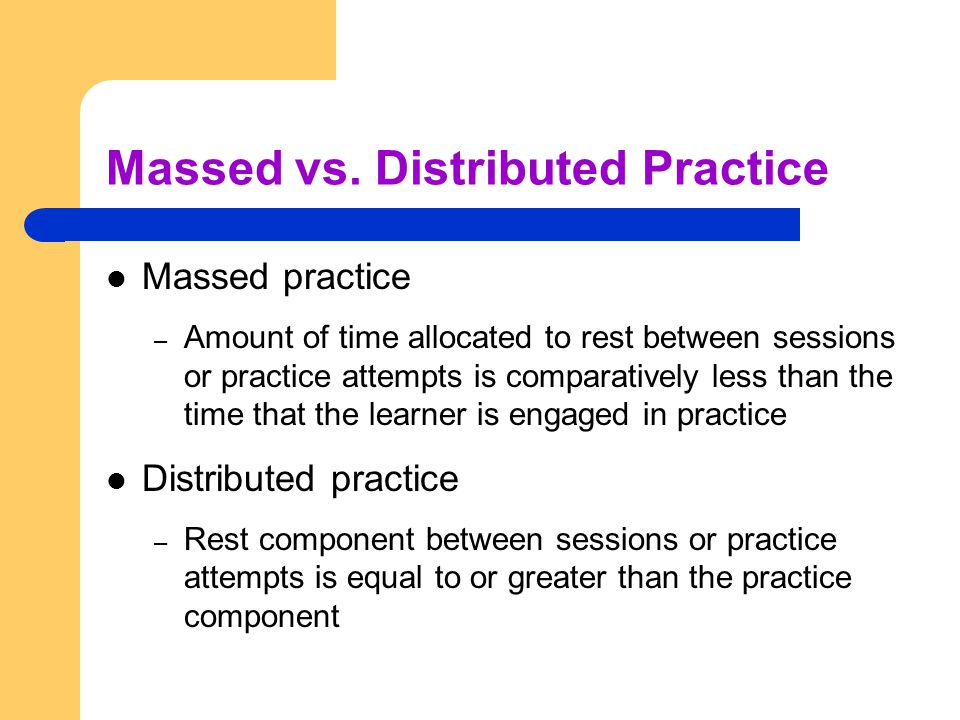

- Focused stimulation (massed practice) is a more effective teaching strategy than varied stimulation (distributed practice).

- The more feedback, the better.

- Repeated reading of passages is the best way to learn text information.

- More therapy is always better.

- The most effective language and literacy interventions target processing limitations rather than knowledge deficits.

- Telegraphic utterances (e.g., push ball, mommy sock) should not be provided as input for children with limited language.

- Appropriate language goals include increasing levels of mean length of utterance (MLU) and targeting Brown’s (1973) 14 grammatical morphemes.

- Sequencing is an important skill for narrative competence.

Guess what? Only statement 8 of the above quiz is True! Every other statement from the above is FALSE!

Now, let’s talk about why that is!

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

Next, Dr. Kamhi addresses the issue of instructional factors, specifically the importance of “varying conditions of instruction and practice“. Here, he addresses the fact that while contextualized instruction is highly beneficial to learners unless we inject variability and modify various aspects of instruction including context, composition, duration, etc., we ran the risk of limiting our students’ long-term outcomes.

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than treatment intensity” (94).

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than treatment intensity” (94).

He also advocates reducing evaluative feedback to learners to “enhance long-term retention and generalization of motor skills“. While he cites research from studies pertaining to speech production, he adds that language learning could also benefit from this practice as it would reduce conversational disruptions and tunning out on the part of the student.

From there he addresses the limitations of repetition for specific tasks (e.g., text rereading). He emphasizes how important it is for students to recall and retrieve text rather than repeatedly reread it (even without correction), as the latter results in a lack of comprehension/retention of read information.

After that, he discusses treatment intensity. Here he emphasizes the fact that higher dose of instruction will not necessarily result in better therapy outcomes due to the research on the effects of “learning plateaus and threshold effects in language and literacy” (95). We have seen research on this with respect to joint book reading, vocabulary words exposure, etc. As such, at a certain point in time increased intensity may actually result in decreased treatment benefits.

His next point against processing interventions is very near and dear to my heart. Those of you familiar with my blog know that I have devoted a substantial number of posts pertaining to the lack of validity of CAPD diagnosis (as a standalone entity) and urged clinicians to provide language based vs. specific auditory interventions which lack treatment utility. Here, Dr. Kamhi makes a great point that: “Interventions that target processing skills are particularly appealing because they offer the promise of improving language and learning deficits without having to directly target the specific knowledge and skills required to be a proficient speaker, listener, reader, and writer.” (95) The problem is that we have numerous studies on the topic of improvement of isolated skills (e.g., auditory skills, working memory, slow processing, etc.) which clearly indicate lack of effectiveness of these interventions. As such, “practitioners should be highly skeptical of interventions that promise quick fixes for language and learning disabilities” (96).

His next point against processing interventions is very near and dear to my heart. Those of you familiar with my blog know that I have devoted a substantial number of posts pertaining to the lack of validity of CAPD diagnosis (as a standalone entity) and urged clinicians to provide language based vs. specific auditory interventions which lack treatment utility. Here, Dr. Kamhi makes a great point that: “Interventions that target processing skills are particularly appealing because they offer the promise of improving language and learning deficits without having to directly target the specific knowledge and skills required to be a proficient speaker, listener, reader, and writer.” (95) The problem is that we have numerous studies on the topic of improvement of isolated skills (e.g., auditory skills, working memory, slow processing, etc.) which clearly indicate lack of effectiveness of these interventions. As such, “practitioners should be highly skeptical of interventions that promise quick fixes for language and learning disabilities” (96).

Now let us move on to language and particularly the models we provide to our clients to encourage greater verbal output. Research indicates that when clinicians are attempting to expand children’s utterances, they need to provide well-formed language models. Studies show that children select strong input when its surrounded by weaker input (the surrounding weaker syllables make stronger syllables stand out). As such, clinicians should expand upon/comment on what clients are saying with grammatically complete models vs. telegraphic productions.

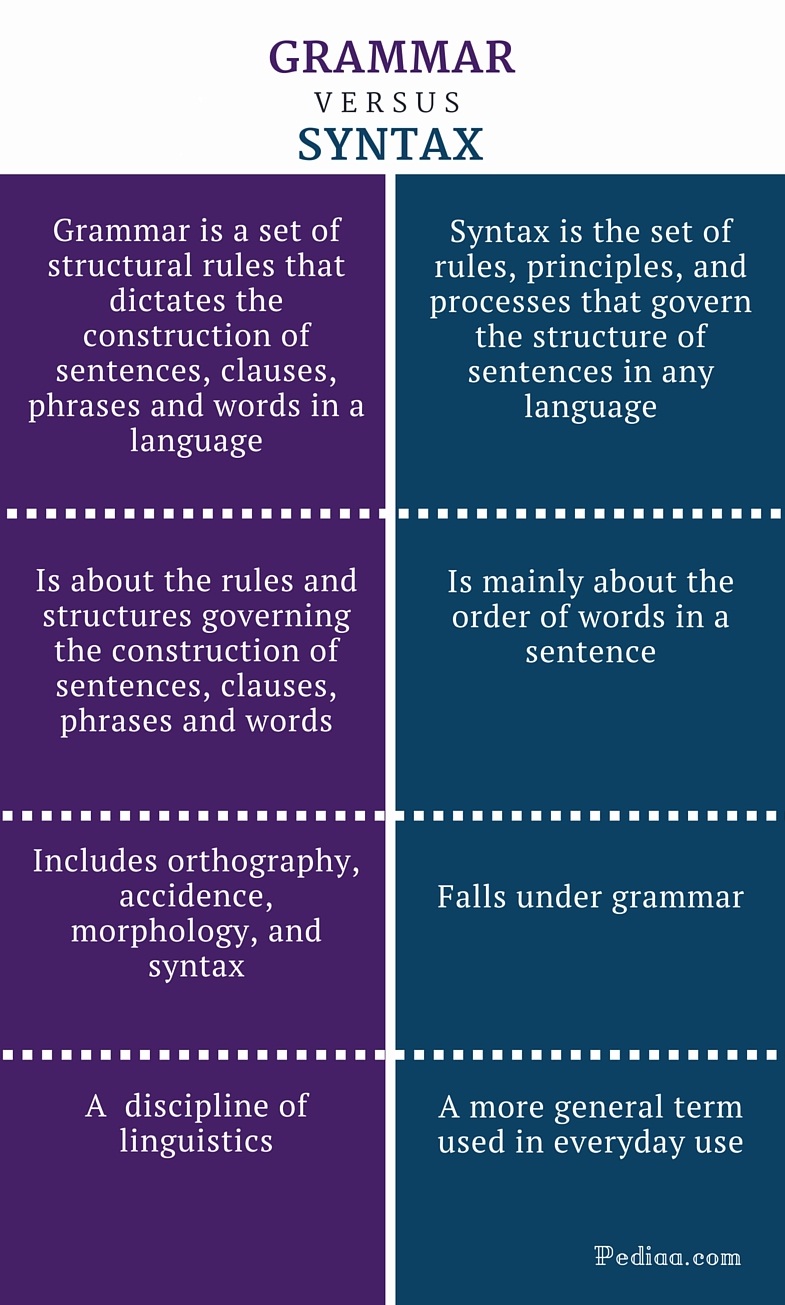

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by Hadley & Holt, 2006; Hadley & Short, 2005 (e.g., Tense Marker Total & Productivity Score) can yield helpful information regarding which grammatical structures to target in therapy.

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by Hadley & Holt, 2006; Hadley & Short, 2005 (e.g., Tense Marker Total & Productivity Score) can yield helpful information regarding which grammatical structures to target in therapy.

With respect to syntax, Dr. Kamhi notes that many clinicians erroneously believe that complex syntax should be targeted when children are much older. The Common Core State Standards do not help this cause further, since according to the CCSS complex syntax should be targeted 2-3 grades, which is far too late. Typically developing children begin developing complex syntax around 2 years of age and begin readily producing it around 3 years of age. As such, clinicians should begin targeting complex syntax in preschool years and not wait until the children have mastered all morphemes and clauses (97)

Finally, Dr. Kamhi wraps up his article by offering suggestions regarding prioritizing intervention goals. Here, he explains that goal prioritization is affected by

- clinician experience and competencies

- the degree of collaboration with other professionals

- type of service delivery model

- client/student factors

He provides a hypothetical case scenario in which the teaching responsibilities are divvied up between three professionals, with SLP in charge of targeting narrative discourse. Here, he explains that targeting narratives does not involve targeting sequencing abilities. “The ability to understand and recall events in a story or script depends on conceptual understanding of the topic and attentional/memory abilities, not sequencing ability.” He emphasizes that sequencing is not a distinct cognitive process that requires isolated treatment. Yet many SLPs “continue to believe that sequencing is a distinct processing skill that needs to be assessed and treated.” (99)

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Furthermore, here it is also important to note that the “sequencing fallacy” affects more than just narratives. It is very prevalent in the intervention process in the form of the ubiquitous “following directions” goal/s. Many clinicians readily create this goal for their clients due to their belief that it will result in functional therapeutic language gains. However, when one really begins to deconstruct this goal, one will realize that it involves a number of discrete abilities including: memory, attention, concept knowledge, inferencing, etc. Consequently, targeting the above goal will not result in any functional gains for the students (their memory abilities will not magically improve as a result of it). Instead, targeting specific language and conceptual goals (e.g., answering questions, producing complex sentences, etc.) and increasing the students’ overall listening comprehension and verbal expression will result in improvements in the areas of attention, memory, and processing, including their ability to follow complex directions.

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same clinical forum, all of which possess highly practical and relevant ideas for therapeutic implementation. They include:

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same clinical forum, all of which possess highly practical and relevant ideas for therapeutic implementation. They include:

- Clinical Scientists Improving Clinical Practices: In Thoughts and Actions

- Approaching Early Grammatical Intervention From a Sentence-Focused Framework

- What Works in Therapy: Further Thoughts on Improving Clinical Practice for Children With Language Disorders

- Improving Clinical Practice: A School-Age and School-Based Perspective

- Improving Clinical Services: Be Aware of Fuzzy Connections Between Principles and Strategies

- One Size Does Not Fit All: Improving Clinical Practice in Older Children and Adolescents With Language and Learning Disorders

- Language Intervention at the Middle School: Complex Talk Reflects Complex Thought

- Using Our Knowledge of Typical Language Development

References:

Kamhi, A. (2014). Improving clinical practices for children with language and learning disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(2), 92-103

Helpful Social Media Resources:

New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

September is quickly approaching and school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) are preparing to go back to work. Many of them are looking to update their arsenal of speech and language materials for the upcoming academic school year.

With that in mind, I wanted to update my readers regarding all the new products I have recently created with a focus on assessment and treatment in speech language pathology. Continue reading New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

Back to School SLP Efficiency Bundles™

September is practically here and many speech language pathologists (SLPs) are looking to efficiently prepare for assessing and treating a variety of clients on their caseloads.

September is practically here and many speech language pathologists (SLPs) are looking to efficiently prepare for assessing and treating a variety of clients on their caseloads.

With that in mind, a few years ago I created SLP Efficiency Bundles™, which are materials highly useful for SLPs working with pediatric clients. These materials are organized by areas of focus for efficient and effective screening, assessment, and treatment of speech and language disorders.

A. General Assessment and Treatment Start-Up Bundle contains 5 downloads for general speech language assessment and treatment planning and includes:

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a Preschool Child

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a School-Aged Child

- Creating a Functional Therapy Plan: Therapy Goals & SOAP Note Documentation

- Selecting Clinical Materials for Pediatric Therapy

- Types and Levels of Cues and Prompts in Speech Language Therapy

B. The Checklists Bundle contains 7 checklists relevant to screening and assessment in speech language pathology

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a Preschool Child 3:00-6:11 years of age

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a School-Aged Child 7:00-11:11 years of age

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents 12-18 years of age

- Language Processing Deficits (LPD) Checklist for School Aged Children 7:00-11:11 years of age

- Language Processing Deficits (LPD) Checklist for Preschool Children 3:00-6:11 years of age

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children 7:00-11:11 years of age

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children 3:00-6:11 years of age

C. Social Pragmatic Assessment and Treatment Bundle contains 6 downloads for social pragmatic assessment and treatment planning (from 18 months through school age) and includes:

- Recognizing the Warning Signs of Social Emotional Difficulties in Language Impaired Toddlers and Preschoolers

- Behavior Management Strategies for Speech Language Pathologists

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children

- Assessing Social Pragmatic Skills of School Aged Children

- Treatment of Social Pragmatic Deficits in School Aged Children

D. Multicultural Assessment and Treatment Bundle contains 2 downloads relevant to assessment and treatment of bilingual/multicultural children

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

E. Narrative Assessment Bundle contains 3 downloads relevant to narrative assessment

- Narrative Assessments of Preschool and School Aged Children

- Understanding Complex Sentences

- Vocabulary Development: Working with Disadvantaged Populations

F. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Assessment and Treatment Bundle contains 3 downloads relevant to FASD assessment and treatment

- Orofacial Observations of At-Risk Children

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: An Overview of Deficits

- Speech Language Assessment and Treatment of Children With Alcohol Related Disorders

G. Psychiatric Disorders Bundle contains 7 downloads relevant to language assessment and treatment in psychiatrically impaired children

- Recognizing the Warning Signs of Social Emotional Difficulties in Language Impaired Toddlers and Preschoolers

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children

- Assessing Social Skills in Children with Psychiatric Disturbances

- Improving Social Skills of Children with Psychiatric Disturbances

- Behavior Management Strategies for Speech Language Pathologists

- Differential Diagnosis Of ADHD In Speech Language Pathology

You can find these bundles on SALE in my online store by clicking on the individual bundle links above. You can also purchase these products individually in my online store by clicking HERE.

Dear SLPs, Here’s What You Need to Know About Internationally Adopted Children

In the past several years there has been a sharp decline in international adoptions. Whereas in 2004, Americans adopted a record high of 22,989 children from overseas, in 2015, only 5,647 children (a record low in 30 years) were adopted from abroad by American citizens.

In the past several years there has been a sharp decline in international adoptions. Whereas in 2004, Americans adopted a record high of 22,989 children from overseas, in 2015, only 5,647 children (a record low in 30 years) were adopted from abroad by American citizens.

Primary Data Source: Data Source: U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

Secondary Data Source: Why Did International Adoption Suddenly End?

Despite a sharp decline in adoptions many SLPs still frequently continue to receive internationally adopted (IA) children for assessment as well as treatment – immediately post adoption as well as a number of years post-institutionalization.

In the age of social media, it may be very easy to pose questions and receive instantaneous responses on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter with respect to assessment and treatment recommendations. However, it is very important to understand that many SLPs, who lack direct clinical experience in international adoptions may chime in with inappropriate recommendations with respect to the assessment or treatment of these children.

Consequently, it is important to identify reputable sources of information when it comes to speech-language assessment of internationally adopted children.

There are a number of researchers in both US and abroad who specialize in speech-language abilities of Internationally Adopted children. This list includes (but is by far not limited to) the following authors:

- Boris Gindis

- Sharon Glennen

- Deborah Hwa-Froelich

- Kathleen A. Scott

- Jenny A. Roberts

- Karen E. Pollock

- M. Gay Masters

- Monica Dalen

The works of these researchers can be readily accessed in the ASHA Journals or via ResearchGate.

Meanwhile, here are some basic facts regarding internationally adopted children that all SLPs and parents need to know.

Demographics:

- A greater number of older, preschool and school-aged children and fewer number of infants and toddlers are placed for adoption (Selman, 2012).

- Significant increase in special needs adoptions from Eastern European countries (e.g., Ukraine, Kazhakstan, etc.) as well as China. The vast majority of Internationally Adopted children arrive to the United States with significant physical, linguistic, and cognitive disabilities as well as mental health problems. Consequently, it is important for schools to immediately provide the children with a host of services including speech-language therapy, immediately post-arrival.

- It is also important to know that in the vast majority of cases the child’s linguistic, cognitive, or mental health deficits may not be documented in the adoption records due to poor record keeping, lack of access to adequate healthcare or often to ensure their “adoptability”. As such, parental interviews and anecdotal evidence become the primary source of information regarding these children’s social and academic functioning in their respective birth countries.

The question of bilingualism:

- Internationally Adopted children are NOT bilingual children! In fact, the vast majority of internationally adopted children will very rapidly lose their birth language, in a period of 2-3 months post arrival (Gindis, 2005), since they are most often adopted by parents who do not speak the child’s birth language and as such are unable/unwilling to maintain it.

- IA children do not need to be placed in ESL classes since they are not bilingual children. Not only are IA children not bilingual, they are also not ‘truly’ monolingual since their first language is lost rather rapidly, while their second language has been gained minimally at the time of loss.

- IA children need to acquire Cognitive Language Mastery (CLM) which is language needed for formal academic learning. This includes listening, speaking, reading, and writing about subject area content material including analyzing, synthesizing, judging and evaluating presented information. This level of language learning is essential for a child to succeed in school. CLM takes years and years to master, especially because, IA children did not have the same foundation of knowledge and stimulation as bilingual children in their birth countries.

Assessment Parameters:

- IA children’s language abilities should be retested and monitored at regular intervals during the first several years post arrival.

- Glennen (2007) recommends 3 evaluations during the first year post arrival, with annual reevaluations thereafter.

- Hough & Kaczmarek (2011) recommend a reevaluation schedule of 3-4 times a year for a period of two years, post arrival because some IA children continue to present with language-based deficits many years (5+) post-adoption.

- If an SLP speaking the child’s first language is available the window of opportunity to assess in the first language is very limited (~2-3 months at most).

- Similarly, an assessment with an interpreter is recommended immediately post arrival from the birth country for a period of approximately the same time.

- If an SLP speaking the child’s first language is not available English-speaking SLP should consider assessing the child in English between 3-6 months post arrival (depending on the child and the situational constraints) in order to determine the speed with which s/he are acquiring English language abilities

- Children should be demonstrating rapid language gains in the areas of receptive language, vocabulary as well as articulation (Glennen 2007, 2009)

- Dynamic assessment is highly recommended

- It is important to remember that language and literacy deficits are not always very apparent and can manifest during any given period post arrival

To treat or NOT to Treat?

- “Any child with a known history of speech and language delays in the sending country should be considered to have true delays or disorders and should receive speech and language services after adoption.” (Glennen, 2009, p.52)

- IA children with medical diagnoses, which impact their speech language abilities should be assessed and considered for S-L therapy services as well (Ladage, 2009).

Helpful Links:

- Elleseff, T (2013) Changing Trends in International Adoption: Implications for Speech-Language Pathologists. Perspectives on Global Issues in Communication Sciences and Related Disorders, 3: 45-53

- Assessing Behaviorally Impaired Students: Why Background History Matters!

- Dear School Professionals Please Be Aware of This

- What parents need to know about speech-language assessment of older internationally adopted children

- Understanding the risks of social pragmatic deficits in post institutionalized internationally adopted (IA) children

- Understanding the extent of speech and language delays in older internationally adopted children

References:

- Gindis, B. (2005). Cognitive, language, and educational issues of children adopted from overseas orphanages. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 4 (3): 290-315.

- Glennen, S (2009) Speech and language guidelines for children adopted from abroad at older ages. Topics in language Disorders 29, 50-64.

- Ladage, J. S. (2009). Medical Issues in International Adoption and Their Influence on Language Development. Topics in Language Disorders , 29 (1), 6-17.

- Selman P. (2012) Global trends in Intercountry Adoption 2000-2010. New York: National Council for Adoption, 2012.

- Selman P. The global decline of intercountry adoption: What lies ahead?. Social Policy and Society 2012, 11(3), 381-397.

Additional Helpful References:

- Abrines, N., Barcons, N., Brun, C., Marre, D., Sartini, C., & Fumadó, V. (2012). Comparing ADHD symptom levels in children adopted from Eastern Europe and from other regions: discussing possible factors involved. Children and Youth Services Review, 34 (9) 1903-1908.

- Balachova, T et al (2010). Changing physicians’ knowledge, skills and attitudes to prevent FASD in Russia: 800. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 34(6) Sup 2:210A.

- Barcons-Castel, N, Fornieles-Deu,A, & Costas-Moragas, C (2011). International adoption: assessment of adaptive and maladaptive behavior of adopted minors in Spain. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14 (1): 123-132.

- Beverly, B., McGuinness, T., & Blanton, D. (2008). Communication challenges for children adopted from the former Soviet Union. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39, 1-11.

- Cohen, N. & Barwick, M. (1996). Comorbidity of language and social-emotional disorders: comparison of psychiatric outpatients and their siblings. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(2), 192-200.

- Croft, C et al, (2007). Early adolescent outcomes of institutionally-deprived and nondeprived adoptees: II. Language as a protective factor and a vulnerable outcome. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 31–44.

- Dalen, M. (2001). School performances among internationally adopted children in Norway. Adoption Quarterly, 5(2), 39-57.

- Dalen, M. (1995). Learning difficulties among inter-country adopted children. Nordisk pedagogikk, 15 (No. 4), 195-208

- Davies, J., & Bledsoe, J. (2005). Prenatal alcohol and drug exposures in adoption. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 1369–1393.

- Desmarais, C., Roeber, B. J., Smith, M. E., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Sentence comprehension in post-institutionalized school-age children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55, 45-54

- Eigsti, I. M., Weitzman, C., Schuh, J. M., de Marchena, A., & Casey, B. J. (2011). Language and cognitive outcomes in internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 629-646.

- Geren, J., Snedeker, J., & Ax, L. (2005). Starting over: a preliminary study of early lexical and syntactic development in internationally-adopted preschoolers. Seminars in Speech & Language, 26:44-54.

- Gindis (2008) Abrupt native language loss in international adoptees. Advance for Speech/Language Pathologists and Audiologists. 18(51): 5.

- Gindis, B. (2005). Cognitive, language, and educational issues of children adopted from overseas orphanages. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 4 (3): 290-315. Gindis, B. (1999) Language-related issues for international adoptees and adoptive families. In: T. Tepper, L. Hannon, D. Sandstrom, Eds. “International Adoption: Challenges and Opportunities.” PNPIC, Meadow Lands , PA. , pp. 98-108

- Glennen, S (2009) Speech and language guidelines for children adopted from abroad at older ages. Topics in language Disorders 29, 50-64.

- Glennen, S. (2007) Speech and language in children adopted internationally at older ages. Perspectives on Communication Disorders in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 14, 17–20.

- Glennen, S., & Bright, B. J. (2005). Five years later: language in school-age internally adopted children. Seminars in Speech and Language, 26, 86-101.

- Glennen, S. & Masters, G. (2002). Typical and atypical language development in infants and toddlers adopted from Eastern Europe. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 44, 417-433

- Gordina, A (2009) Parent Handout: The Dream Referral, Unpublished Manuscript.

- Hough, S., & Kaczmarek, L. (2011). Language and reading outcomes in young children adopted from Eastern European orphanages. Journal of Early Intervention, 33, 51-57.

- Hwa-Froelich, D (2012) Childhood maltreatment and communication development. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 13: 43-53;

- Jacobs, E., Miller, L. C., & Tirella, G. (2010). Developmental and behavioral performance of internationally adopted preschoolers: a pilot study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 15–29.

- Jenista, J., & Chapman, D. (1987). Medical problems of foreign-born adopted children. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 141, 298–302.

- Johnson, D. (2000). Long-term medical issues in international adoptees. Pediatric Annals, 29, 234–241.

- Judge, S. (2003). Developmental recovery and deficit in children adopted from Eastern European orphanages. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 34, 49–62.

- Krakow, R. A., & Roberts, J. (2003). Acquisitions of English vocabulary by young Chinese adoptees. Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders, 1, 169-176

- Ladage, J. S. (2009). Medical issues in international adoption and their influence on language development. Topics in Language Disorders , 29 (1), 6-17.

- Loman, M. M., Wiik, K. L., Frenn, K. A., Pollak, S. D., & Gunnar, M. R. (2009). Post-institutionalized children’s development: growth, cognitive, and language outcomes. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, 30, 426–434.

- McLaughlin, B., Gesi Blanchard, A., & Osanai, Y. (1995). Assessing language development in bilingual preschool children. Washington, D.C.: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education.

- Miller, L., Chan, W., Litvinova, A., Rubin, A., Tirella, L., & Cermak, S. (2007). Medical diagnoses and growth of children residing in Russian orphanages. Acta Paediatrica, 96, 1765–1769.

- Miller, L., Chan, W., Litvinova, A., Rubin, A., Comfort, K., Tirella, L., et al. (2006). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in children residing in Russian orphanages: A phenotypic survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 531–538.

- Miller, L. (2005). Preadoption counseling and evaluation of the referral. In L. Miller (Ed.), The Handbook of International Adoption Medicine (pp. 67-86). NewYork: Oxford.

- Pollock, K. E. (2005) Early language growth in children adopted from China: preliminary normative data. Seminars in Speech and Language, 26, 22-32.

- Roberts, J., Pollock, K., Krakow, R., Price, J., Fulmer, K., & Wang, P. (2005). Language development in preschool-aged children adopted from China. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 93–107.

- Scott, K.A., Roberts, J.A., & Glennen, S. (2011). How well children who are internationally do adopted acquire language? A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 54. 1153-69.

- Scott, K.A., & Roberts, J. (2011). Making evidence-based decisions for children who are internationally adopted. Evidence-Based Practice Briefs. 6(3), 1-16.

- Scott, K.A., & Roberts, J. (2007) language development of internationally adopted children: the school-age years. Perspectives on Communication Disorders in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 14: 12-17.

- Selman P. (2012a) Global trends in intercountry adoption 2000-2010. New York: National Council for Adoption.

- Selman P (2012b). The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century. In: Gibbons, J.L., Rotabi, K.S, ed. Intercountry Adoption: Policies, Practices and Outcomes. London: Ashgate Press.

- Selman, P. (2010) “Intercountry adoption in Europe 1998–2009: patterns, trends and issues,” Adoption & Fostering, 34 (1): 4-19.

- Silliman, E. R., & Scott, C. M. (2009). Research-based oral language intervention routes to the academic language of literacy: Finding the right road. In S. A. Rosenfield & V. Wise Berninger (Eds.), Implementing evidence-based academic interventions in school (pp. 107–145). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tarullo, A. R., Bruce, J., & Gunnar, M. (2007). False belief and emotion understanding in post-institutionalized children. Social Development, 16, 57-78

- Tarullo, A. & Gunnar, M. R. (2005). Institutional rearing and deficits in social relatedness: Possible mechanisms and processes. Cognitie, Creier, Comportament [Cognition, Brain, Behavior], 9, 329-342.

- Varavikova, E. A. & Balachova, T. N. (2010). Strategies to implement physician training in FAS prevention as a part of preventive care in primary health settings: P120.Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 34(8) Sup 3:119A.

- Welsh, J. A., & Viana, A. G. (2012). Developmental outcomes of children adopted internationally. Adoption Quarterly, 15, 241-264.

Why Are My Child’s Test Scores Dropping?

“I just don’t understand,” says a parent bewilderingly, “she’s receiving so many different therapies and tutoring every week, but her scores on educational, speech-language, and psychological testing just keep dropping!”

“I just don’t understand,” says a parent bewilderingly, “she’s receiving so many different therapies and tutoring every week, but her scores on educational, speech-language, and psychological testing just keep dropping!”

I hear a variation of this comment far too frequently in both my private practice as well as outpatient school in hospital setting, from parents looking for an explanation regarding the decline of their children’s standardized test scores in both cognitive (IQ) and linguistic domains. That is why today I wanted to take a moment to write this blog post to explain a few reasons behind this phenomenon.

Children with language impairments represent a highly diverse group, which exists along a continuum. Some children’s deficits may be mild while others far more severe. Some children may receive very little intervention services and thrive academically, while others can receive inordinate amount of interventions and still very limitedly benefit from them. To put it in very simplistic terms, the above is due to two significant influences – the interaction between the child’s (1) genetic makeup and (2) environmental factors.

There is a reason why language disorders are considered developmental. Firstly, these difficulties are apparent from a young age when the child’s language just begins to develop. Secondly, the trajectory of the child’s language deficits also develops along with the child and can progress/lag based on the child’s genetic predisposition, resiliency, parental input, as well as schooling and academically based interventions.

Let us discuss some of the reasons why standardized testing results may decline for select students who are receiving a variety of support services and interventions.

Ineffective Interventions due to Misdiagnosis

Sometimes, lack of appropriate/relevant intervention provision may be responsible for it. Let’s take an example of a misdiagnosis of alcohol related deficits as Autism, which I have frequently encountered in my private practice, when performing second opinion testing and consultations. Unfortunately, the above is not uncommon. Many children with alcohol-related impairments may present with significant social emotional dysregulation coupled with significant externalizing behavior manifestations. As a result, without a thorough differential diagnosis they may be frequently diagnosed with ASD and then provided with ABA therapy services for years with little to no benefit.

Ineffective Interventions due to Lack of Comprehensive Testing

Let us examine another example of a student with average intelligence but poor reading performance. The student may do well in school up to certain grade but then may begin to flounder academically. Because only the student’s reading abilities ‘seem’ to be adversely impacted, no comprehensive language and literacy evaluations are performed. The student may receive undifferentiated extra reading support in school while his scores may continue to drop.

Once the situation ‘gets bad enough’, the student’s language and literacy abilities may be comprehensively assessed. In a vast majority of situations these type of assessments yield the following results:

- The student’s oral language expression as well as higher order language abilities are adversely affected and require targeted language intervention

- The undifferentiated reading intervention provided to the student was NOT targeting actual areas of weaknesses

As can be seen from above examples, targeted intervention is hugely important and, in a number of cases, may be responsible for the student’s declining performance. However, that is not always the case.

What if it was definitively confirmed that the student was indeed diagnosed appropriately and was receiving quality services but still continued to decline academically. What then?

Well, we know that many children with genetic disorders (Down Syndrome, Fragile X, etc.) as well as intellectual disabilities (ID) can make incredibly impressive gains in a variety of developmental areas (e.g., gross/fine motor skills, speech/language, socio-emotional, ADL, etc.) but their gains will not be on par with peers without these diagnoses.

The situation becomes much more complicated when children without ID (or with mild intellectual deficits) and varying degrees of language impairment, receive effective therapies, work very hard in therapy, yet continue to be perpetually behind their peers when it comes to making academic gains. This occurs because of a phenomenon known as Cumulative Cognitive Deficit (CCD).

The Effect of Cumulative Cognitive Deficit (CCD) on Academic Performance

According to Gindis (2005) CCD “refers to a downward trend in the measured intelligence and/or scholastic achievement of culturally/socially disadvantaged children relative to age-appropriate societal norms and expectations” (p. 304). Gindis further elucidates by quoting Satler (1992): “The theory behind cumulative deficit is that children who are deprived of enriching cognitive experiences during their early years are less able to profit from environmental situations because of a mismatch between their cognitive schemata and the requirements of the new (or advanced) learning situation” (pp. 575-576).

So who are the children potentially at risk for CCD?

One such group are internationally (and domestically) adopted as well as foster care children. A number of studies show that due to the early life hardships associated with prenatal trauma (e.g., maternal substance abuse, lack of adequate prenatal care, etc.) as well as postnatal stress (e.g., adverse effect of institutionalization), many of these children have much poorer social and academic outcomes despite being adopted by well-to-do, educated parents who continue to provide them with exceptional care in all aspects of their academic and social development.

Another group, are children with diagnosed/suspected psychiatric impairments and concomitant overt/hidden language deficits. Depending on the degree and persistence of the psychiatric impairment, in addition to having intermittent access to classroom academics and therapy interventions, the quality of their therapy may be affected by the course of their illness. Combined with sporadic nature of interventions this may result in them falling further and further behind their peers with respect to social and academic outcomes.

A third group (as mentioned previously) are children with genetic syndromes, neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., Autism) and intellectual disabilities. Here, it is very important to explicitly state that children with diagnosed or suspected alcohol related deficits (FASD) are particularly at risk due to the lack of consensus/training regarding FAS detection/diagnosis. Consequently, these children may evidence a steady ‘decline’ on standardized testing despite exhibiting steady functional gains in therapy.

Brief Standardized Testing Score Tutorial:

When we look at norm-referenced testing results, score interpretation can be quite daunting. For the sake of simplicity, I’d like to restrict this discussion to two types of scores: raw scores and standard scores.

The raw score is the number of items the child answered correctly on a test or a subtest. However, raw scores need to be interpreted to be meaningful. For example, a 9 year old student can attain a raw score of 12 on a subtest of a particular test (e.g., Listening Comprehension Test-2 or LCT-2). Without more information, the raw score has no meaning. If the test consisted of 15 questions, a raw score of 12 would be an average score. Alternatively, if the subtest had 36 questions, a raw score of 12 would be significantly below-average (e.g., Test of Problem Solving-3 or TOPS-3).

Consequently, the raw score needs to be converted to a standard score. Standard scores compare the student’s performance on a test to the performance of other students his/her age. Many standardized language assessments have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. Thus, scores between 85 and 115 are considered to be in the average range of functioning.

Now lets discuss testing performance variation across time. Let’s say an 8.6 year old student took the above mentioned LCT-2 and attained poor standard scores on all subtests. That student qualifies for services and receives them for a period of one year. At that time the LCT-2 is re-administered once again and much to the parents surprise the student’s standard scores appear to be even lower than when he had taken the test as an eight year old (illustration below).

Results of The Listening Comprehension Test -2 (LCT-2): Age: 8:4

| Subtests | Raw Score | Standard Score | Percentile Rank | Description |

| Main Idea | 5 | 67 | 2 | Severely Impaired |

| Details | 2 | 63 | 1 | Severely Impaired |

| Reasoning | 2 | 69 | 2 | Severely Impaired |

| Vocabulary | 0 | Below Norms | Below Norms | Profoundly Impaired |

| Understanding Messages | 0 | <61 | <1 | Profoundly Impaired |

| Total Test Score | 9 | <63 | 1 | Profoundly Impaired |

(Mean = 100, Standard Deviation = +/-15)

Results of The Listening Comprehension Test -2 (LCT-2): Age: 9.6

| Subtests | Raw Score | Standard Score | Percentile Rank | Description |

| Main Idea | 6 | 60 | 0 | Severely Impaired |

| Details | 5 | 66 | 1 | Severely Impaired |

| Reasoning | 3 | 62 | 1 | Severely Impaired |

| Vocabulary | 4 | 74 | 4 | Moderately Impaired |

| Understanding Messages | 2 | 54 | 0 | Profoundly Impaired |

| Total Test Score | 20 | <64 | 1 | Profoundly Impaired |

(Mean = 100, Standard Deviation = +/-15)

However, if one looks at the raw score column on the far left, one can see that the student as a 9 year old actually answered more questions than as an 8 year old and his total raw test score went up by 11 points.

The above is a perfect illustration of CCD in action. The student was able to answer more questions on the test but because academic, linguistic, and cognitive demands continue to steadily increase with age, this quantitative improvement in performance (increase in total number of questions answered) did not result in qualitative improvement in performance (increase in standard scores).

In the first part of this series I have introduced the concept of Cumulative Cognitive Deficit and its effect on academic performance. Stay tuned for part II of this series which describes what parents and professionals can do to improve functional performance of students with Cumulative Cognitive Deficit.

References:

- Bowers, L., Huisingh, R., & LoGiudice, C. (2006). The Listening Comprehension Test-2 (LCT-2). East Moline, IL: LinguiSystems, Inc.

- Bowers, L., Huisingh, R., & LoGiudice, C. (2005). The Test of Problem Solving 3-Elementary (TOPS-3). East Moline, IL: LinguiSystems.

- Gindis, B. (2005). Cognitive, language, and educational issues of children adopted from overseas orphanages. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 4 (3): 290-315.

- Sattler, J. M. (1992). Assessment of Children. Revised and updated 3rd edition. San Diego: Jerome M. Sattler.

Parent Consultation Services

Today I’d like to officially introduce a new parent consultation service which I had originally initiated with a few out-of-state clients through my practice a few years ago.

Today I’d like to officially introduce a new parent consultation service which I had originally initiated with a few out-of-state clients through my practice a few years ago.

The idea for this service came after numerous parents contacted me and initiated dialogue via email and phone calls regarding the services/assessments needed for their monolingual/bilingual internationally/domestically adopted or biological children with complex communication needs. Here are some details about it.

Parent consultations is a service provided to clients who live outside Smart Speech Therapy LLC geographical area (e.g., non-new Jersey residents) who are interested in comprehensive specialized in-depth consultations and recommendations regarding what type of follow up speech language services they should be seeking/obtaining in their own geographical area for their children as well as what type of carryover activities they should be doing with their children at home.

Consultations are provided with the focus on the following specialization areas with a focus on comprehensive assessment and intervention recommendations:

- Language and Literacy

- Children with Social Communication (Pragmatic) Disorders

- Bilingual and Multicultural Children

- Post-institutionalized Internationally Adopted Children

- Children with Psychiatric and Emotional Disturbances

- Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

The initial consultation length of this service is 1 hour. Clients are asked to forward their child’s records prior to the consultation for review, fill out several relevant intakes and questionnaires, as well as record a short video (3-5 minutes). The instructions regarding video content will be provided to them following session payment.

Upon purchasing a consultation the client will be immediately emailed the necessary paperwork to fill out as well as potential dates and times for the consultation to take place. Afternoon, Evening and Weekend hours are available for the client’s convenience. In cases of emergencies consultations may be rescheduled at the client’s/Smart Speech Therapy’s mutual convenience.

Refunds are available during a 3 day grace period if a mutually convenient time could not be selected for the consultation. Please note that fees will not be refundable from the time the scheduled consultation begins.

Following the consultation the client has the option of requesting a written detailed consultation report at an additional cost, which is determined based on the therapist’s hourly rate. For further information click HERE. You can also call 917-916-7487 or email tatyana.elleseff@smartspeechtherapy.com if you wanted to find out whether this service is right for you.

Below is a past parent consultation testimonial.

International Adoption Consultation Parent Testimonial (11/11/13)

I found Tatyana and Smart Speech Therapy online while searching for information about internationally adopted kids and speech evaluations. We’d already taken our three year old son to a local SLP but were very unsatisfied with her opinion, and we just didn’t know where to turn. Upon finding the articles and blogs written by Tatyana, I felt like I’d finally found someone who understood the language learning process unique to adopted kids, and whose writings could also help me in my meetings with the local school system as I sought special education services for my son.

I could have never predicted then just how much Tatyana and Smart Speech Therapy would help us. I used the online contact form on her website to see if Tatyana could offer us any services or recommendations, even though we are in Virginia and far outside her typical service area. She offered us an in-depth phone consultation that was probably one of the most informative, supportive and helpful phone calls I’ve had in the eight months since adopting my son. Through a series of videos, questionnaires, and emails, she was better able to understand my son’s speech difficulties and background than any of the other sources I’d sought help from. She was able to explain to me, a lay person, exactly what was going on with our son’s speech, comprehension, and learning difficulties in a way that a) added urgency to our situation without causing us to panic, b) provided me with a ton of research-orientated information for our local school system to review, and c) validated all my concerns and gut instincts that had previously been brushed aside by other physicians and professionals who kept telling us to “wait and see”.

After our phone call, we contracted Tatyana to provide us with an in-depth consultation report that we are now using with our local school and child rehab center to get our son the help he needs. Without that report, I don’t think we would have had the access to these services or the backing we needed to get people to seriously listen to us. It’s a terrible place to be in when you think something might be wrong, but you’re not sure and no one around you is listening. Tatyana listened to us, but more importantly, she looked at our son as a specific kid with a specific past and specific needs. We were more than just a number or file to her – and we’ve never even actually met in person! The best move we’ve could’ve made was sending her that email that day. We are so appreciative.

Kristen, P. Charlottesville, VA