Three years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“. In it, I used 4 very different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Today I would like to expound more on that post in order to explain, what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?

Three years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“. In it, I used 4 very different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Today I would like to expound more on that post in order to explain, what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?

Category: Dyslexia

Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Because the children I assess, often require supplementary reading instruction services, many parents frequently ask me how they can best determine if a reading specialist has the right experience to help their child learn how to read. So today’s blog post describes what type of knowledge reading specialists ought to possess and what type of questions parents (and other professionals) can ask them in order to determine their approaches to treating literacy-related difficulties of struggling learners. Continue reading Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Because the children I assess, often require supplementary reading instruction services, many parents frequently ask me how they can best determine if a reading specialist has the right experience to help their child learn how to read. So today’s blog post describes what type of knowledge reading specialists ought to possess and what type of questions parents (and other professionals) can ask them in order to determine their approaches to treating literacy-related difficulties of struggling learners. Continue reading Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Free Literacy Resources for Parents and Professionals

SLPs are constantly on the lookout for good quality affordable materials in the area of literacy. However, what many clinicians may not realize is that there are massive amounts of FREE evidence-based literacy-related resources available online for their use. These materials can be easily adapted or implemented as is, by parents, teachers, speech-language pathologists, as well as other literacy-focused professionals (e.g., tutors, etc.).

SLPs are constantly on the lookout for good quality affordable materials in the area of literacy. However, what many clinicians may not realize is that there are massive amounts of FREE evidence-based literacy-related resources available online for their use. These materials can be easily adapted or implemented as is, by parents, teachers, speech-language pathologists, as well as other literacy-focused professionals (e.g., tutors, etc.).

Below, I have compiled a rather modest list of my preferred resources (including a few articles) for children aged Pre-K-12 grade pertaining to the following literacy-related areas: Continue reading Free Literacy Resources for Parents and Professionals

Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

FREE Resources for Working with Russian Speaking Clients: Part III Introduction to “Dyslexia”

Given the rising interest in recent years in the role of SLPs in the treatment of reading disorders, today I wanted to share with parents and professionals several reputable FREE resources on the subject of “dyslexia” in Russian-speaking children.

Given the rising interest in recent years in the role of SLPs in the treatment of reading disorders, today I wanted to share with parents and professionals several reputable FREE resources on the subject of “dyslexia” in Russian-speaking children.

Now if you already knew that there was a dearth of resources on the topic of treating Russian speaking children with language disorders then it will not come as a complete shock to you that very few legitimate sources exist on this subject.

First up is the Report on the Russian Language for the World Dyslexia Forum 2010 by Dr. Grigorenko, the coauthor of the Dyslexia Debate. This 25-page report contains important information including Reading/Writing Acquisition of Russian in the Context of Typical and Atypical Development as well as on the state of Individuals with Dyslexia in Russia.

First up is the Report on the Russian Language for the World Dyslexia Forum 2010 by Dr. Grigorenko, the coauthor of the Dyslexia Debate. This 25-page report contains important information including Reading/Writing Acquisition of Russian in the Context of Typical and Atypical Development as well as on the state of Individuals with Dyslexia in Russia.

Next up is this delightful presentation entitled: “If John were Ivan: Would he fail in reading? Dyslexia & dysgraphia in Russian“. It is a veritable treasure trove of useful information on the topics of:

Next up is this delightful presentation entitled: “If John were Ivan: Would he fail in reading? Dyslexia & dysgraphia in Russian“. It is a veritable treasure trove of useful information on the topics of:

- The Russian language

- Literacy in Russia (Russian Federation)

- Dyslexia in Russia

- Definition

- Identification

- Policy

- Examples of good practice

- Teaching reading/language arts

• In regular schools

• In specialized settings - Encouraging children to learn

- Teaching reading/language arts

Now let us move on to the “The Role of Phonology, Morphology, and Orthography in English and Russian Spelling” which discusses that “phonology and morphology contribute more for spelling of English words while orthography and morphology contribute more to the spelling of Russian words“. It also provides clinicians with access to the stimuli from the orthographic awareness and spelling tests in both English and Russian, listed in its appendices.

Now let us move on to the “The Role of Phonology, Morphology, and Orthography in English and Russian Spelling” which discusses that “phonology and morphology contribute more for spelling of English words while orthography and morphology contribute more to the spelling of Russian words“. It also provides clinicians with access to the stimuli from the orthographic awareness and spelling tests in both English and Russian, listed in its appendices.

Finally, for parents and Russian speaking professionals, there’s an excellent article entitled, “Дислексия” in which Dr. Grigorenko comprehensively discusses the state of the field in Russian including information on its causes, rehabilitation, etc.

Related Helpful Resources:

- Анализ Нарративов У Детей С Недоразвитием Речи (Narrative Discourse Analysis in Children With Speech Underdevelopment)

- Narrative production weakness in Russian dyslexics: Linguistic or procedural limitations?

It’s All Due to …Language: How Subtle Symptoms Can Cause Serious Academic Deficits

Scenario: Len is a 7-2-year-old, 2nd-grade student who struggles with reading and writing in the classroom. He is very bright and has a high average IQ, yet when he is speaking he frequently can’t get his point across to others due to excessive linguistic reformulations and word-finding difficulties. The problem is that Len passed all the typical educational and language testing with flying colors, receiving average scores across the board on various tests including the Woodcock-Johnson Fourth Edition (WJ-IV) and the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 (CELF-5). Stranger still is the fact that he aced Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Second Edition (CTOPP-2), with flying colors, so he is not even eligible for a “dyslexia” diagnosis. Len is clearly struggling in the classroom with coherently expressing self, telling stories, understanding what he is reading, as well as putting his thoughts on paper. His parents have compiled impressively huge folders containing examples of his struggles. Yet because of his performance on the basic standardized assessment batteries, Len does not qualify for any functional assistance in the school setting, despite being virtually functionally illiterate in second grade.

Scenario: Len is a 7-2-year-old, 2nd-grade student who struggles with reading and writing in the classroom. He is very bright and has a high average IQ, yet when he is speaking he frequently can’t get his point across to others due to excessive linguistic reformulations and word-finding difficulties. The problem is that Len passed all the typical educational and language testing with flying colors, receiving average scores across the board on various tests including the Woodcock-Johnson Fourth Edition (WJ-IV) and the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 (CELF-5). Stranger still is the fact that he aced Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Second Edition (CTOPP-2), with flying colors, so he is not even eligible for a “dyslexia” diagnosis. Len is clearly struggling in the classroom with coherently expressing self, telling stories, understanding what he is reading, as well as putting his thoughts on paper. His parents have compiled impressively huge folders containing examples of his struggles. Yet because of his performance on the basic standardized assessment batteries, Len does not qualify for any functional assistance in the school setting, despite being virtually functionally illiterate in second grade.

The truth is that Len is quite a familiar figure to many SLPs, who at one time or another have encountered such a student and asked for guidance regarding the appropriate accommodations and services for him on various SLP-geared social media forums. But what makes Len such an enigma, one may inquire? Surely if the child had tangible deficits, wouldn’t standardized testing at least partially reveal them?

Well, it all depends really, on what type of testing was administered to Len in the first place. A few years ago I wrote a post entitled: “What Research Shows About the Functional Relevance of Standardized Language Tests“. What researchers found is that there is a “lack of a correlation between frequency of test use and test accuracy, measured both in terms of sensitivity/specificity and mean difference scores” (Betz et al, 2012, 141). Furthermore, they also found that the most frequently used tests were the comprehensive assessments including the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals and the Preschool Language Scale as well as one-word vocabulary tests such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test”. Most damaging finding was the fact that: “frequently SLPs did not follow up the comprehensive standardized testing with domain-specific assessments (critical thinking, social communication, etc.) but instead used the vocabulary testing as a second measure”.(Betz et al, 2012, 140)

In other words, many SLPs only use the tests at hand rather than the RIGHT tests aimed at identifying the student’s specific deficits. But the problem doesn’t actually stop there. Due to the variation in psychometric properties of various tests, many children with language impairment are overlooked by standardized tests by receiving scores within the average range or not receiving low enough scores to qualify for services.

Thus, “the clinical consequence is that a child who truly has a language impairment has a roughly equal chance of being correctly or incorrectly identified, depending on the test that he or she is given.” Furthermore, “even if a child is diagnosed accurately as language impaired at one point in time, future diagnoses may lead to the false perception that the child has recovered, depending on the test(s) that he or she has been given (Spaulding, Plante & Farinella, 2006, 69).”

There’s of course yet another factor affecting our hypothetical client and that is his relatively young age. This is especially evident with many educational and language testing for children in the 5-7 age group. Because the bar is set so low, concept-wise for these age-groups, many children with moderate language and literacy deficits can pass these tests with flying colors, only to be flagged by them literally two years later and be identified with deficits, far too late in the game. Coupled with the fact that many SLPs do not utilize non-standardized measures to supplement their assessments, Len is in a pretty serious predicament.

But what if there was a do-over? What could we do differently for Len to rectify this situation? For starters, we need to pay careful attention to his deficits profile in order to choose appropriate tests to evaluate his areas of needs. The above can be accomplished via a number of ways. The SLP can interview Len’s teacher and his caregiver/s in order to obtain a summary of his pressing deficits. Depending on the extent of the reported deficits the SLP can also provide them with a referral checklist to mark off the most significant areas of need.

In Len’s case, we already have a pretty good idea regarding what’s going on. We know that he passed basic language and educational testing, so in the words of Dr. Geraldine Wallach, we need to keep “peeling the onion” via the administration of more sensitive tests to tap into Len’s reported areas of deficits which include: word-retrieval, narrative production, as well as reading and writing.

For that purpose, Len is a good candidate for the administration of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS), which was developed to identify language and literacy disorders, has good psychometric properties, and contains subtests for assessment of relevant skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school-age children.

For that purpose, Len is a good candidate for the administration of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS), which was developed to identify language and literacy disorders, has good psychometric properties, and contains subtests for assessment of relevant skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school-age children.

Given Len’s reported history of narrative production deficits, Len is also a good candidate for the administration of the Social Language Development Test Elementary (SLDTE). Here’s why. Research indicates that narrative weaknesses significantly correlate with social communication deficits (Norbury, Gemmell & Paul, 2014). As such, it’s not just children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who present with impaired narrative abilities. Many children with developmental language impairment (DLD) (#devlangdis) can present with significant narrative deficits affecting their social and academic functioning, which means that their social communication abilities need to be tested to confirm/rule out presence of these difficulties.

Given Len’s reported history of narrative production deficits, Len is also a good candidate for the administration of the Social Language Development Test Elementary (SLDTE). Here’s why. Research indicates that narrative weaknesses significantly correlate with social communication deficits (Norbury, Gemmell & Paul, 2014). As such, it’s not just children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who present with impaired narrative abilities. Many children with developmental language impairment (DLD) (#devlangdis) can present with significant narrative deficits affecting their social and academic functioning, which means that their social communication abilities need to be tested to confirm/rule out presence of these difficulties.

However, standardized tests are not enough, since even the best-standardized tests have significant limitations. As such, several non-standardized assessments in the areas of narrative production, reading, and writing, may be recommended for Len to meaningfully supplement his testing.

Let’s begin with an informal narrative assessment which provides detailed information regarding microstructural and macrostructural aspects of storytelling as well as child’s thought processes and socio-emotional functioning. My nonstandardized narrative assessments are based on the book elicitation recommendations from the SALT website. For 2nd graders, I use the book by Helen Lester entitled Pookins Gets Her Way. I first read the story to the child, then cover up the words and ask the child to retell the story based on pictures. I read the story first because: “the model narrative presents the events, plot structure, and words that the narrator is to retell, which allows more reliable scoring than a generated story that can go in many directions” (Allen et al, 2012, p. 207).

As the child is retelling his story I digitally record him using the Voice Memos application on my iPhone, for a later transcription and thorough analysis. During storytelling, I only use the prompts: ‘What else can you tell me?’ and ‘Can you tell me more?’ to elicit additional information. I try not to prompt the child excessively since I am interested in cataloging all of his narrative-based deficits. After I transcribe the sample, I analyze it and make sure that I include the transcription and a detailed write-up in the body of my report, so parents and professionals can see and understand the nature of the child’s errors/weaknesses.

Now we are ready to move on to a brief nonstandardized reading assessment. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Reading for Comprehension, which contains books for grades 1-8. After I confirm with either the parent or the child’s teacher that the selected passage is reflective of the complexity of work presented in the classroom for his grade level, I ask the child to read the text. As the child is reading, I calculate the correct number of words he reads per minute as well as what type of errors the child is exhibiting during reading. Then I ask the child to state the main idea of the text, summarize its key points as well as define select text embedded vocabulary words and answer a few, verbally presented reading comprehension questions. After that, I provide the child with accompanying 5 multiple choice question worksheet and ask the child to complete it. I analyze my results in order to determine whether I have accurately captured the child’s reading profile.

Now we are ready to move on to a brief nonstandardized reading assessment. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Reading for Comprehension, which contains books for grades 1-8. After I confirm with either the parent or the child’s teacher that the selected passage is reflective of the complexity of work presented in the classroom for his grade level, I ask the child to read the text. As the child is reading, I calculate the correct number of words he reads per minute as well as what type of errors the child is exhibiting during reading. Then I ask the child to state the main idea of the text, summarize its key points as well as define select text embedded vocabulary words and answer a few, verbally presented reading comprehension questions. After that, I provide the child with accompanying 5 multiple choice question worksheet and ask the child to complete it. I analyze my results in order to determine whether I have accurately captured the child’s reading profile.

Finally, if any additional information is needed, I administer a nonstandardized writing assessment, which I base on the Common Core State Standards for 2nd grade. For this task, I provide a student with a writing prompt common for second grade and give him a period of 15-20 minutes to generate a writing sample. I then analyze the writing sample with respect to contextual conventions (punctuation, capitalization, grammar, and syntax) as well as story composition (overall coherence and cohesion of the written sample).

The above relatively short assessment battery (2 standardized tests and 3 informal assessment tasks) which takes approximately 2-2.5 hours to administer, allows me to create a comprehensive profile of the child’s language and literacy strengths and needs. It also allows me to generate targeted goals in order to begin effective and meaningful remediation of the child’s deficits.

Children like Len will, unfortunately, remain unidentified unless they are administered more sensitive tasks to better understand their subtle pattern of deficits. Consequently, to ensure that they do not fall through the cracks of our educational system due to misguided overreliance on a limited number of standardized assessments, it is very important that professionals select the right assessments, rather than the assessments at hand, in order to accurately determine the child’s areas of needs.

References:

- Allen, M, Ukrainetz, T & Carswell, A (2012) The narrative language performance of three types of at-risk first-grade readers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43(2), 205-221.

- Betz et al. (2013) Factors Influencing the Selection of Standardized Tests for the Diagnosis of Specific Language Impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 44, 133-146.

- Hasbrouck, J. & Tindal, G. A. (2006). Oral reading fluency norms: A valuable assessment tool for reading teachers. The Reading Teacher. 59(7), 636-644.).

- Norbury, C. F., Gemmell, T., & Paul, R. (2014). Pragmatics abilities in narrative production: a cross-disorder comparison. Journal of child language, 41(03), 485-510.

- Peña, E.D., Spaulding, T.J., & Plante, E. (2006). The Composition of Normative Groups and Diagnostic Decision Making: Shooting Ourselves in the Foot. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 247-254.

- Spaulding, Plante & Farinella (2006) Eligibility Criteria for Language Impairment: Is the Low End of Normal Always Appropriate? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37, 61-72.

- Spaulding, Szulga, & Figueria (2012) Using Norm-Referenced Tests to Determine Severity of Language Impairment in Children: Disconnect Between U.S. Policy Makers and Test Developers. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 43, 176-190.

Making Our Interventions Count or What’s Research Got To Do With It?

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “What’s Memes Got To Do With It?” which summarized key points of Dr. Alan G. Kamhi’s 2004 article: “A Meme’s Eye View of Speech-Language Pathology“. It delved into answering the following question: “Why do some terms, labels, ideas, and constructs [in our field] prevail whereas others fail to gain acceptance?”.

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “What’s Memes Got To Do With It?” which summarized key points of Dr. Alan G. Kamhi’s 2004 article: “A Meme’s Eye View of Speech-Language Pathology“. It delved into answering the following question: “Why do some terms, labels, ideas, and constructs [in our field] prevail whereas others fail to gain acceptance?”.

Today I would like to reference another article by Dr. Kamhi written in 2014, entitled “Improving Clinical Practices for Children With Language and Learning Disorders“.

This article was written to address the gaps between research and clinical practice with respect to the implementation of EBP for intervention purposes.

Dr. Kamhi begins the article by posing 10 True or False questions for his readers:

- Learning is easier than generalization.

- Instruction that is constant and predictable is more effective than instruction that varies the conditions of learning and practice.

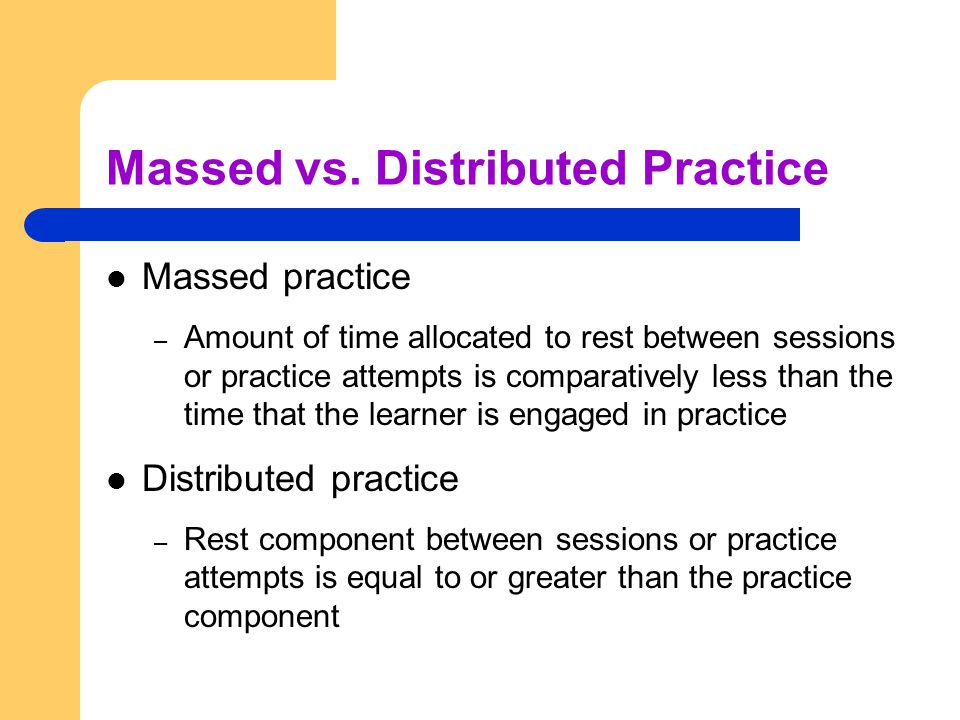

- Focused stimulation (massed practice) is a more effective teaching strategy than varied stimulation (distributed practice).

- The more feedback, the better.

- Repeated reading of passages is the best way to learn text information.

- More therapy is always better.

- The most effective language and literacy interventions target processing limitations rather than knowledge deficits.

- Telegraphic utterances (e.g., push ball, mommy sock) should not be provided as input for children with limited language.

- Appropriate language goals include increasing levels of mean length of utterance (MLU) and targeting Brown’s (1973) 14 grammatical morphemes.

- Sequencing is an important skill for narrative competence.

Guess what? Only statement 8 of the above quiz is True! Every other statement from the above is FALSE!

Now, let’s talk about why that is!

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

Next, Dr. Kamhi addresses the issue of instructional factors, specifically the importance of “varying conditions of instruction and practice“. Here, he addresses the fact that while contextualized instruction is highly beneficial to learners unless we inject variability and modify various aspects of instruction including context, composition, duration, etc., we ran the risk of limiting our students’ long-term outcomes.

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than treatment intensity” (94).

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than treatment intensity” (94).

He also advocates reducing evaluative feedback to learners to “enhance long-term retention and generalization of motor skills“. While he cites research from studies pertaining to speech production, he adds that language learning could also benefit from this practice as it would reduce conversational disruptions and tunning out on the part of the student.

From there he addresses the limitations of repetition for specific tasks (e.g., text rereading). He emphasizes how important it is for students to recall and retrieve text rather than repeatedly reread it (even without correction), as the latter results in a lack of comprehension/retention of read information.

After that, he discusses treatment intensity. Here he emphasizes the fact that higher dose of instruction will not necessarily result in better therapy outcomes due to the research on the effects of “learning plateaus and threshold effects in language and literacy” (95). We have seen research on this with respect to joint book reading, vocabulary words exposure, etc. As such, at a certain point in time increased intensity may actually result in decreased treatment benefits.

His next point against processing interventions is very near and dear to my heart. Those of you familiar with my blog know that I have devoted a substantial number of posts pertaining to the lack of validity of CAPD diagnosis (as a standalone entity) and urged clinicians to provide language based vs. specific auditory interventions which lack treatment utility. Here, Dr. Kamhi makes a great point that: “Interventions that target processing skills are particularly appealing because they offer the promise of improving language and learning deficits without having to directly target the specific knowledge and skills required to be a proficient speaker, listener, reader, and writer.” (95) The problem is that we have numerous studies on the topic of improvement of isolated skills (e.g., auditory skills, working memory, slow processing, etc.) which clearly indicate lack of effectiveness of these interventions. As such, “practitioners should be highly skeptical of interventions that promise quick fixes for language and learning disabilities” (96).

His next point against processing interventions is very near and dear to my heart. Those of you familiar with my blog know that I have devoted a substantial number of posts pertaining to the lack of validity of CAPD diagnosis (as a standalone entity) and urged clinicians to provide language based vs. specific auditory interventions which lack treatment utility. Here, Dr. Kamhi makes a great point that: “Interventions that target processing skills are particularly appealing because they offer the promise of improving language and learning deficits without having to directly target the specific knowledge and skills required to be a proficient speaker, listener, reader, and writer.” (95) The problem is that we have numerous studies on the topic of improvement of isolated skills (e.g., auditory skills, working memory, slow processing, etc.) which clearly indicate lack of effectiveness of these interventions. As such, “practitioners should be highly skeptical of interventions that promise quick fixes for language and learning disabilities” (96).

Now let us move on to language and particularly the models we provide to our clients to encourage greater verbal output. Research indicates that when clinicians are attempting to expand children’s utterances, they need to provide well-formed language models. Studies show that children select strong input when its surrounded by weaker input (the surrounding weaker syllables make stronger syllables stand out). As such, clinicians should expand upon/comment on what clients are saying with grammatically complete models vs. telegraphic productions.

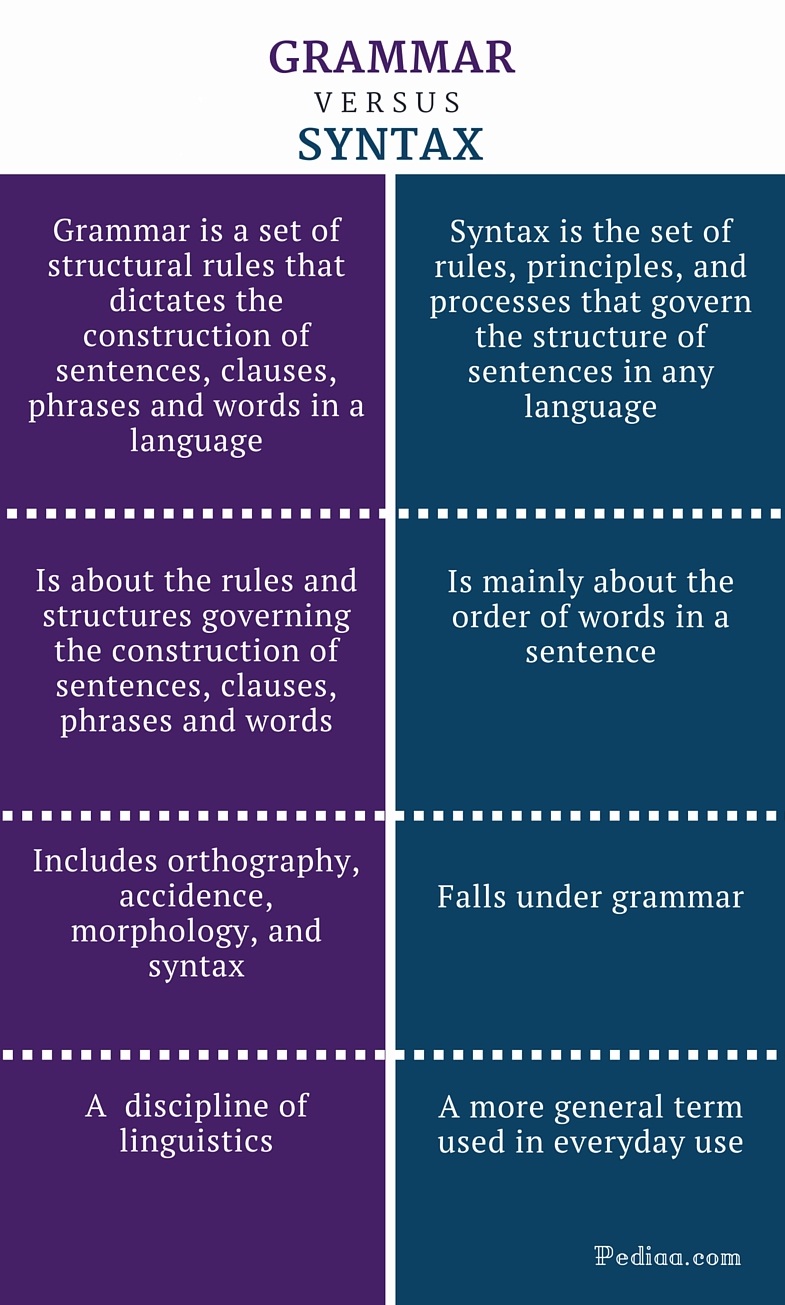

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by Hadley & Holt, 2006; Hadley & Short, 2005 (e.g., Tense Marker Total & Productivity Score) can yield helpful information regarding which grammatical structures to target in therapy.

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by Hadley & Holt, 2006; Hadley & Short, 2005 (e.g., Tense Marker Total & Productivity Score) can yield helpful information regarding which grammatical structures to target in therapy.

With respect to syntax, Dr. Kamhi notes that many clinicians erroneously believe that complex syntax should be targeted when children are much older. The Common Core State Standards do not help this cause further, since according to the CCSS complex syntax should be targeted 2-3 grades, which is far too late. Typically developing children begin developing complex syntax around 2 years of age and begin readily producing it around 3 years of age. As such, clinicians should begin targeting complex syntax in preschool years and not wait until the children have mastered all morphemes and clauses (97)

Finally, Dr. Kamhi wraps up his article by offering suggestions regarding prioritizing intervention goals. Here, he explains that goal prioritization is affected by

- clinician experience and competencies

- the degree of collaboration with other professionals

- type of service delivery model

- client/student factors

He provides a hypothetical case scenario in which the teaching responsibilities are divvied up between three professionals, with SLP in charge of targeting narrative discourse. Here, he explains that targeting narratives does not involve targeting sequencing abilities. “The ability to understand and recall events in a story or script depends on conceptual understanding of the topic and attentional/memory abilities, not sequencing ability.” He emphasizes that sequencing is not a distinct cognitive process that requires isolated treatment. Yet many SLPs “continue to believe that sequencing is a distinct processing skill that needs to be assessed and treated.” (99)

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Furthermore, here it is also important to note that the “sequencing fallacy” affects more than just narratives. It is very prevalent in the intervention process in the form of the ubiquitous “following directions” goal/s. Many clinicians readily create this goal for their clients due to their belief that it will result in functional therapeutic language gains. However, when one really begins to deconstruct this goal, one will realize that it involves a number of discrete abilities including: memory, attention, concept knowledge, inferencing, etc. Consequently, targeting the above goal will not result in any functional gains for the students (their memory abilities will not magically improve as a result of it). Instead, targeting specific language and conceptual goals (e.g., answering questions, producing complex sentences, etc.) and increasing the students’ overall listening comprehension and verbal expression will result in improvements in the areas of attention, memory, and processing, including their ability to follow complex directions.

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same clinical forum, all of which possess highly practical and relevant ideas for therapeutic implementation. They include:

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same clinical forum, all of which possess highly practical and relevant ideas for therapeutic implementation. They include:

- Clinical Scientists Improving Clinical Practices: In Thoughts and Actions

- Approaching Early Grammatical Intervention From a Sentence-Focused Framework

- What Works in Therapy: Further Thoughts on Improving Clinical Practice for Children With Language Disorders

- Improving Clinical Practice: A School-Age and School-Based Perspective

- Improving Clinical Services: Be Aware of Fuzzy Connections Between Principles and Strategies

- One Size Does Not Fit All: Improving Clinical Practice in Older Children and Adolescents With Language and Learning Disorders

- Language Intervention at the Middle School: Complex Talk Reflects Complex Thought

- Using Our Knowledge of Typical Language Development

References:

Kamhi, A. (2014). Improving clinical practices for children with language and learning disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(2), 92-103

Helpful Social Media Resources:

New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

September is quickly approaching and school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) are preparing to go back to work. Many of them are looking to update their arsenal of speech and language materials for the upcoming academic school year.

With that in mind, I wanted to update my readers regarding all the new products I have recently created with a focus on assessment and treatment in speech language pathology. Continue reading New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

Treatment of Children with “APD”: What SLPs Need to Know

In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

More and more studies in the fields of audiology and speech-language pathology began confirming the lack of validity of APD as a standalone (or useful) diagnosis. To illustrate, in June 2015, the American Journal of Audiology published an article by David DeBonis entitled: “It Is Time to Rethink Central Auditory Processing Disorder Protocols for School-Aged Children.” In this article, DeBonis pointed out numerous inconsistencies involved in APD testing and concluded that “routine use of APD test protocols cannot be supported” and that [APD] “intervention needs to be contextualized and functional” (DeBonis, 2015, p. 124) Continue reading Treatment of Children with “APD”: What SLPs Need to Know

A Focus on Literacy

In recent months, I have been focusing more and more on speaking engagements as well as the development of products with an explicit focus on assessment and intervention of literacy in speech-language pathology. Today I’d like to introduce 4 of my recently developed products pertinent to assessment and treatment of literacy in speech-language pathology.

In recent months, I have been focusing more and more on speaking engagements as well as the development of products with an explicit focus on assessment and intervention of literacy in speech-language pathology. Today I’d like to introduce 4 of my recently developed products pertinent to assessment and treatment of literacy in speech-language pathology.

First up is the Comprehensive Assessment and Treatment of Literacy Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

First up is the Comprehensive Assessment and Treatment of Literacy Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

which describes how speech-language pathologists can effectively assess and treat children with literacy disorders, (reading, spelling, and writing deficits including dyslexia) from preschool through adolescence. It explains the impact of language disorders on literacy development, lists formal and informal assessment instruments and procedures, as well as describes the importance of assessing higher order language skills for literacy purposes. It reviews components of effective reading instruction including phonological awareness, orthographic knowledge, vocabulary awareness, morphological awareness, as well as reading fluency and comprehension. Finally, it provides recommendations on how components of effective reading instruction can be cohesively integrated into speech-language therapy sessions in order to improve literacy abilities of children with language disorders and learning disabilities.

Next up is a product entitled From Wordless Picture Books to Reading Instruction: Effective Strategies for SLPs Working with Intellectually Impaired Students. This product discusses how to address the development of critical thinking skills through a variety of picture books utilizing the framework outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy: Cognitive Domain which encompasses the categories of knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in children with intellectual impairments. It shares a number of similarities with the above product as it also reviews components of effective reading instruction for children with language and intellectual disabilities as well as provides recommendations on how to integrate reading instruction effectively into speech-language therapy sessions.

Next up is a product entitled From Wordless Picture Books to Reading Instruction: Effective Strategies for SLPs Working with Intellectually Impaired Students. This product discusses how to address the development of critical thinking skills through a variety of picture books utilizing the framework outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy: Cognitive Domain which encompasses the categories of knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in children with intellectual impairments. It shares a number of similarities with the above product as it also reviews components of effective reading instruction for children with language and intellectual disabilities as well as provides recommendations on how to integrate reading instruction effectively into speech-language therapy sessions.

The product Improving Critical Thinking Skills via Picture Books in Children with Language Disorders is also available for sale on its own with a focus on only teaching critical thinking skills via the use of picture books.

The product Improving Critical Thinking Skills via Picture Books in Children with Language Disorders is also available for sale on its own with a focus on only teaching critical thinking skills via the use of picture books.

Finally, my last product Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions focuses on how bilingual speech-language pathologists (SLPs) can effectively assess and intervene with simultaneously bilingual and multicultural children (with stronger academic English language skills) diagnosed with linguistically-based literacy impairments. Topics include components of effective literacy assessments for simultaneously bilingual children (with stronger English abilities), best instructional literacy practices, translanguaging support strategies, critical questions relevant to the provision of effective interventions, as well as use of accommodations, modifications and compensatory strategies for improvement of bilingual students’ performance in social and academic settings.

Finally, my last product Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions focuses on how bilingual speech-language pathologists (SLPs) can effectively assess and intervene with simultaneously bilingual and multicultural children (with stronger academic English language skills) diagnosed with linguistically-based literacy impairments. Topics include components of effective literacy assessments for simultaneously bilingual children (with stronger English abilities), best instructional literacy practices, translanguaging support strategies, critical questions relevant to the provision of effective interventions, as well as use of accommodations, modifications and compensatory strategies for improvement of bilingual students’ performance in social and academic settings.

You can find these and other products in my online store (HERE).

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Dynamic Assessment of Bilingual and Multicultural Learners in Speech-Language Pathology

- Differential Assessment and Treatment of Processing Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

- Practical Strategies for Monolingual SLPs Assessing and Treating Bilingual Children

- The Checklists Bundle

- General Assessment and Treatment Start Up Bundle

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Narrative Assessment and Treatment Bundle

- Social Pragmatic Assessment and Treatment Bundle

- Psychiatric Disorders Bundle