Today’s post will make a number of people quite angry and is intended to be controversial! Why? Because controversy promotes critical thinking, broadens perspectives, allows to acquire better knowledge of the construct in question as well as ultimately guides better decision making on the part of the parties in question. So why the lengthy disclaimer? Because today via the use of the latest research publications, I would like discuss the fact that the diagnosis of Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) or what some may know as Central Auditory Processing Disorder (CAPD) is NOT valid!

Here are just a few reasons why:

- There is a strong desire for the (C)APD label on the part of those encountering processing difficulties, yet once the label is given no direct/specific auditory interventions are provided by the audiologist. Subsequent to the diagnosis, confusion ensues regarding the type, frequency, and duration of service provision (typically performed by the SLP) as well as what those services should actually constitute

- Recommendations for training deficits specific areas such as working memory, auditory discrimination, auditory sequencing, etc., do not functionally transfer into practice and fail to create generalization affect

- Recommendations for specific costly auditory training programs such Auditory Integration Training (AIT), The Listening Program (TLP), Fast ForWord® (FFW) at the exclusion of all others, without the provision of a detailed breakdown of the child’s deficit areas often cause an incursion of unnecessary expenses for parents and professionals and are found to be INEFFECTIVE or limitedly effective in the long run

- General audiological recommendations for accommodations (e.g., FM systems, etc.) are frequently unnecessary, and may actually exacerbate the isolation effect while in no way alleviating the student’s deficits, which require direct and targeted intervention

- Auditory deficits don’t cause speech, language, and academic learning difficulties

- Numerous non-linguistic based disorders can be misdiagnosed as (C)APD without differential diagnosis

- (C)APD testing is hugely influenced by non-auditory factors grounded in higher order cognitive and linguistic processes

- Presently there’s no no clear performance criteria to make the (C)APD diagnosis

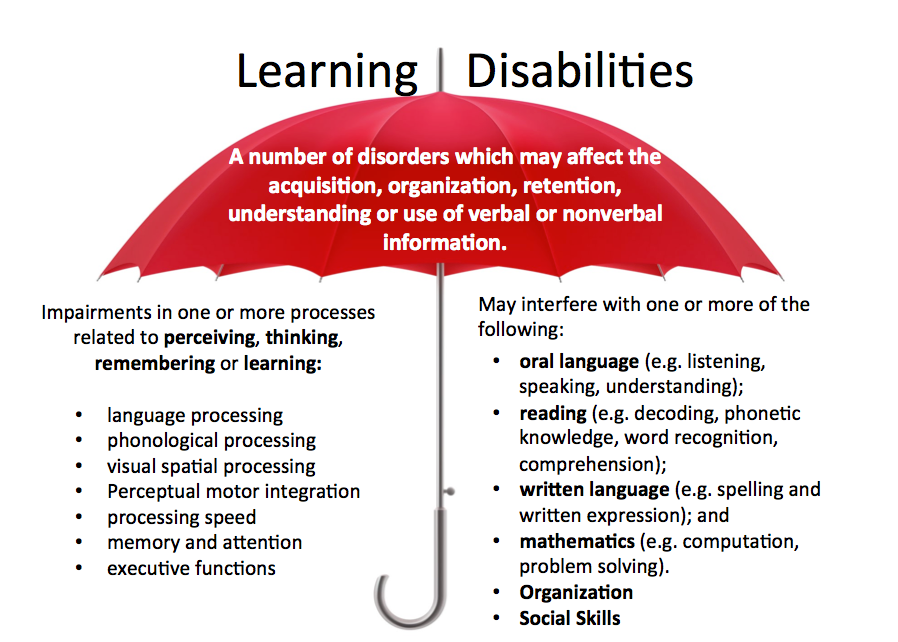

- The diagnosis of (C)APD is appealing because it presents a more attractive explanation than the diagnoses of language and learning disabilities for children with processing deficits

- The diagnosis of (C)APD may often detract from identifying legitimate language based deficits in the areas of comprehension, expression, social communication and literacy development, as the result of which these areas will not get adequate therapeutic attention by relevant professionals

A few words on (C)APD popularity, well sort of:

(C)APD is currently rampantly diagnosed in the United States, Australia and New Zealand, and is even beginning to be diagnosed in the United Kingdom (Dawes & Bishop, 2009). However, presently, (C)APD is not a mainstream diagnostic classifications in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) nor is part of an actual educational classification in United States. Already many of you can see the beginnings of the controversy. If this diagnoses is so popular and so prevalent why is that major psychological and educational governing bodies such as American Psychiatric Association and the US Department of Education still do not officially recognize it?

(C)APD symptomology:

A. Student presents with difficulty processing information efficiently

- Requires increased processing time to respond to questions

- Presents like s/he are ignoring the speaker

- May request frequent repetition of presented information from speakers

- Difficulty following long sentences

- Difficulty keeping up with class discussions in group settings

- Poor listening abilities under noisy conditions may be interpreted as “distractibility”

B. Student has difficulty maintaining attention on presented tasks

- Frequent loss of focus

- Difficulty completing assignments on their own

C. Student has poor short term memory – difficulty remembering instructions and directions or verbally presented information

D.Student has difficulty with phonemic awareness, reading and spelling

- Poor ability to recognize and produce rhyming words

- Poor segmentation abilities (separation of sentences, syllables and sounds)

- Poor sound manipulation abilities (isolation, deletion, substitution, blending, etc)

- Poor sound letter identification abilities

- Poor vowel recognition abilities

- Poor decoding

- Poor comprehension

- Spelling errors

- Limited/disorganized writing

E. The combination of above factors may result in generalized deficits across the board, affecting the child’s social and academic performance:

- Poor reading comprehension

- Poor oral and written expression

- Disorganized thinking (e.g., disjointed narrative production)

- Sequencing errors (recalling/retelling information in order, following recipes, etc)

- Poor message interpretation

- Difficulty making inferences

- Misinterpreting the meaning of abstract information

That is exactly what Dawes & Bishop, stated in 2009, when they asserted that “a child who is regarded as having a specific learning disability by one group of experts may be given an APD diagnosis by another.” They concluded that: “APD, as currently diagnosed, is not a coherent category, but that rather than abandoning the construct, we need to develop improved methods for assessment and diagnosis, with a focus on interdisciplinary evaluation“.

Let us now deconstruct each of the above statements with the assistance of direct quotes from current research.

1. (C)APD – what is it good for? Child goes to an audiologist and receives an ambiguous battery of (C)APD testing with unclear qualification criteria (more on that below). There are some abnormal findings, so the audiologist states that the child has (C)APD, recommends accommodations and modifications, services in the form of speech language therapy with a focus on auditory training (more below) and/or some form of program similar to Fast ForWord®, and doesn’t see the child again for some time (maybe even years). Since the child is now being seen by an SLP, who by the way frequently has no idea what to do with that child based on the ambiguous audiological findings, what exactly did the diagnosis of (C) APD just accomplish?

2. Processing Skills Training – Say What? In 2011 Fey and colleagues (many notable audiologists and speech language pathologists) conducted a systematic review of 25 journal articles on the efficacy of interventions for school-age children with auditory processing disorder (C)APD. Their review found no compelling evidence that auditory interventions provided any unique benefit to auditory, language, or academic outcomes for children with diagnoses of (C)APD or language disorder.

Presently there is no valid evidence that targeting specific processing skills such as auditory discrimination, auditory sequencing, phonological memory, working memory, or rapid serial naming actually improves children’s ‘auditory processing’, language or reading abilities (Fey et al., 2011).

To illustrate further, Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013 performed a meta analysis of 23 working memory training studies. They found no evidence that memory training was an effective intervention for children with ADHD or dyslexia as it did not lead to better performance outside of the tasks presented within the memory tests. They concluded: “In the light of such evidence, it seems very difficult to justify the use of working memory training programs in relation to the treatment of reading and language disorders.” Further adding: “Our findings also cast strong doubt on claims that working memory training is effective in improving cognitive ability and scholastic attainment.” (Melby-Lervåg, 2013, p. 282).

3. The trouble with prescriptive programs. (C)APD assessments often yield recommendations for a number of specific costly prescriptive programs such as AIT, FFW, etc.. As humans we are “attracted to interventions that promise relatively rapid improvements in language and academic skills. Interventions that target processing abilities are appealing because they promise significant improvements in language and reading without having to directly target the specific knowledge and skills required to be a proficient speaker, listener, reader, and writer.” (Kamhi and Wallach, 2012)

These programs claim to improve the child’s processing abilities through music, phonics, hearing distortions, etc. When such recommendations are made parents and professionals are urged to carefully review evidence-based research supported information regarding these prescribed programs in order to determine their effectiveness. Presently, there’s no research to support the use of any of these programs with children presenting with processing difficulties.

Let’s take a look at Fast ForWord®, which is a highly costly program frequently recommended for children with auditory processing deficits. It is designed to help children’s reading and spoken language by training their memory, attention, processing, and sequencing by training 3 to 5 days per week, for 8 to 12 weeks. However, systematic reviews found no sign of a reliable effect of Fast ForWord® on reading or on expressive or receptive spoken language.

Now some of you may legitimately tell me: “How dare you? I’ve tried it with my child and seen great gains”. And that is terrific! However, it is important to note that ANY intervention is better than NO intervention! And there is currently no scientific proof out there that this program works better than other programs aimed directly at improving the children’s reading abilities and listening skills. Furthermore, if the child needs assistance with reading rather than spending the money on Fast ForWord® it would be far more effective to select a systematic Orton-Gillingham (OG) (or similar) reading based program to teach her/him reading!

4. The dreaded FM system! FM systems have become an almost automatic recommendation for children diagnosed with (C)APD but are they actually effective?

Here is what one notable audiologist had to say in the subject. “An FM system brings the speaker’s voice via the mic to the listener via loudspeakers or earphones through an amplifier. Only personal systems appropriate for children with TRUE APD-based auditory distractibility problems (understanding speech in the presence of background noise)”. However, when he did his testing he found that only ~25% of children with (C)APD had issues with hearing speech in noise, the other ~75% didn’t.

Guess what… a recent meta-analysis showed? Lemos et, al, 2009 did a systematic literature review of articles recommending the use of FM systems for APD. They concluded that: “Strong scientific evidence supporting the use of personal FM systems for APD intervention was not found. Since such device is frequently recommended for the treatment of APD, it becomes essential to carry out studies with high scientific evidence that could safely guide clinical decision making on this subject.“

5. (C)APD diagnosis does NOT Language Disorder Make. “There little evidence that auditory perceptual impairments (not referring to hearing deficits) are a significant risk factor for language and academic performance (e.g., Hazan, Messaoud-Galusi, Rosan, Nouwens, & Shakespeare, 2009; Watson & Kidd, 2009)” (Kamhi, 2011, p. 265).

- Watson et al., 2003 found that measures of auditory processing (NOT hearing) had no impact on children’s reading or language abilities in Grades 1 through 4.

- Sharma, Purdy, and Kelly (2009) found that having auditory processing difficulties did not increase the likelihood that a child would have a language or reading disorder.

- Hazan et al., 2009; Ramus et al., 2006) found that despite poor phonological processing abilities, individuals with dyslexia perform within normal limits on measures of speech perception.

(From Kamhi, 2011, p. 268)

6. Are you sure it’s (C)APD?

Without a careful differential diagnosis, numerous non-linguistic based medical, psychiatric neurological, psychological, and cognitive conditions can be misdiagnosed as (C)APD including (but not limited):

- Respiratory Disorders

- Adenoid hypertrophy, asthma, allergic rhinitis

- Metabolic/Endocrine Disorders

- Diabetes hypo/hyperthyroidism

- Hematological Disorders

- Anemia

- Immunological Disorders

- Acquired and congenital immune problems

- Cardiac Disorders

- Congenital and acquired heart disease, syncopy

- Digestive Disorders

- Irritable bowel syndrome, GERD

- Neurological Disorders

- Traumatic Brain Injuries, Tumors, Encephalopathy

- Genetic Disorders

- Fragile X Syndrome

- Toxin Exposure

- Lead, Mercury, Drug Exposure

- Infections and Infestations

- Yeast overgrowth , intestinal worms/parasites

- Sleep Disorders

- Sleep Apnea

- Mental Health Disorders

- Trauma, Anxiety, mood disorders, adjustment disorders

- Sensory Processing Disorders

- Vision, hearing, auditory, tactile

- Acquired Disorders

- FASD

7. (C)APD testing is NOT so PURE

(C)APD testing does not simply consists of pure tone audiometry and is heavily comprised of higher order linguistic and cognitive tasks. Testing requires that the listeners attend to given directions, remember and label the presented auditory sequences, etc, in other words participate in tasks aimed to task their linguistic system and executive functions (DeBonis, 2015)

So what does the research show?

- Wallach (2011) has indicated that (C) APD ‘symptomology’ “reflects broader underlying problems in language comprehension and metalinguistic awareness.

- Dawes and Bishop (2009) compared children with a CAPD to children diagnosed with dyslexia and found similar attention, reading, and language deficits in both groups.

- Kelly et al. (2009) found that 76% of a sample of 68 children with suspected auditory processing disorder also had language impairment with 53% demonstrating decreased auditory attention and 59% demonstrated decreased auditory memory.

- Ferguson et al. (2011) concluded that “the current labels of CAPD and SLI [specific language impairment] may, for all practical purposes, be indistinguishable” (p. 225).

(From DeBonis, 2015 pgs. 126-127)

8. What to Test and How to do it – That IS the Question?

“Despite lofty claims to the contrary, there is no clear consensus concerning the battery of tests that lead to a diagnosis of CAPD.” (Burkard, 2009, p. vii) Presently, neither the American Academy of Audiology nor the American Speech Language Hearing Association have a clear criteria on what testing to administer, how many standard deviations the client has to be in order to qualify, as well as even who is a good candidate for (C)APD testing. (DeBonis, 2015 pg. 125)

As such, presently children diagnosed with (C)APD are diagnosed purely in an arbitrary fashion rather than based on a specific widely accepted standard. To illustrate W. J. Wilson and Arnott (2013) found that “in a sample of records of 150 school-aged children who had completed at least four CAPD tests, rates of diagnosis ranged from 7.3% to 96% depending on the criteria used” (DeBonis, 2015 pg. 125). Are you “processing” what I am saying?

9. Looking for the “Right” Label

As an SLP, I frequently hear the following statement from parents: “We were searching for what was wrong with our child for such a long time; we are so happy that we were finally able to identify that it’s (C)APD.

The above comment is certainly understandable. After all (C)APD sounds manageable! The appeal to it is that presumably if the child undergoes specific auditory interventions to improve deficit areas, s/he will get better and all the problems will go away. In contrast, finding out that the child’s processing difficulties are the result of linguistic deficits in the areas of listening, speaking, reading, and writing can be incredibly overwhelming especially because what we know about the nature of language impairments and that is that more often than not they turn into lifelong learning disabilities.

Some parents and professionals may disagree. They might point out that many children with (C)APD test just fine on generalized language testing and only present with isolated deficits in the areas of attention, memory, as well as phonological processing. Yet here is the problem! General language testing in the form of administration of tests such as the CELF-5 or the CASL does not complete language assessment make!

The same children who test ‘just fine’ on these assessments often test quite poorly on the measures of social communication, executive function, as well as reading. In other words if the professionals dig deep enough they often find out that something which outwardly presents as (C)APD is part of much broader language related issues, which require relevant intervention services. This leads me to my final point below.

10. Missing the Big Picture

“The primacy given to auditory processing abilities has resulted at times in neglect of other cognitive factors” (Cowan et al. 2009, p. 192). Focusing on the diagnosis of (C)APD obscures REAL, language-based deficits in children in question. It forces SLPs to address erroneous therapeutic targets based on AuD recommendations. It makes us ignore the BIG Picture and “Consider non-auditory reasons for listening and comprehension difficulties, such as limitations in working memory, language knowledge, conceptual abilities, attention, and motivation and consequently targeting language, literacy, and knowledge-based goals in therapy.” (Kamhi &Wallach, 2012)

Conclusion:

So what will happen next? Well, I can tell you with certainty that the controversy will certainly not end here! Presently, not only is that there is a fierce academic debate between speech language pathologist and audiologists but there is also a raging debate among audiologists themselves! This controversy will continue for many years among some highly educated people. And SLPs? Well, we will continue seeing numerous children diagnosed with (C)APD. Except, I do hope something will change and that is our collective outlook on how we view ambiguously defined and assessed disorders such as (C)APD.

I sincerely hope that we do not blindly defer to other professions and reject current valid research regarding this controversial diagnosis without first spending some time reflecting and critically reviewing these findings in order to better assist us with making informed and educated decisions regarding our clients’ plan of care.

Click HERE to read the second part of this post, which describes how SLPs SHOULD assess and treat children diagnosed by audiologists with (C)APD.

References:

- Burkard, R. (2009). Foreword. In A. Cacace & D. McFarland (Eds.), Controversies in central auditory processing disorder (pp. vii-viii). San Diego, CA: Plural.

- Cowan, J., Rosen, S., & Moore, D. (2009). Putting the auditory back into auditory processing disorder in children. In Cacace, A., & McFarland, D. (Eds.),Controversies in central auditory processing disorder(pp. 187–197). San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

- Dawes, P., & Bishop, D. (2009). Auditiory processing disorder in relation to developmental disorders of language, communication and attention: A review and critique. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 44, 440–465.

- DeBonis, D. A. (2015) It Is Time to Rethink Central Auditory Processing Disorder Protocols for School-Aged Children. American Journal of Audiology. v. 24, 124-136.

- Ferguson, M. A., Hall, R. L., Moore, D. R., & Riley, A. (2011). Communication, listening, cognitive and speech perception skills in children with auditory processing disorder (APD) or specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54, 211–227.

- Fey, M. E., Richard, G. J., Geffner, D., Kamhi, A. G., Medwetsky, L., Paul, D., Schooling, T. (2011). Auditory processing disorder and auditory/language interventions: An evidence-based systematic review. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 246–264.

- Hazan, V., Messaoud-Galusi, S., Rosen, S., Nouwens, S., Shakespeare, B. (2009). Speech perception abilities of adults with dyslexia: Is there any evidence for a true deficit?. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 52 1510–1529

- Kamhi, A. G. (2011). What speech-language pathologists need to know about auditory processing disorder. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 265–272.

- Kamhi, A & Wallach, G (2012) What Speech-Language Pathologists Need to Know about Auditory Processing Disorders. ASHA Convention Presentation. Atlanta, GA.

- Kelly, A. S., Purdy, S. C., & Sharma, M. (2009). Comorbidity of auditory processing, language, and reading disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 706–722.

- Lemos IC, Jacob RT, Gejao MG, et al. (2009) Frequency modulation (FM) system in auditory processing disorder: An evidence-based practice? Pró-Fono Produtos Especializados para Fonoaudiologia Ltda. 21(3):243-248.

- Melby-Lervåg, M., & Hulme, C. (2013). Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 49, 270–291.

- Ramus, F., White, S., Frith, U. (2006). Weighing the evidence between competing theories of dyslexia.Developmental Science. 9 265–269

- Sharma, M., Purdy, S. C., Kelly, A. S. (2009). Comorbidity of auditory processing, language, and reading disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 52 706–722

- Wallach, G. P. (2011). Peeling the onion of auditory processing disorder: A language/curricular-based perspective. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 273–285.

- Watson, C., Kidd, G. (2009). Associations between auditory abilities, reading, and other language skills in children and adults. Cacace, A., McFarland, D.Controversies in central auditory processing disorder. 218–242 San Diego, CA Plural.

- Wilson, W. J., & Arnott, W. (2013). Using different criteria to diagnose (central) auditory processing disorder: How big a difference does it make? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56, 63–70.

Several years after I started my private speech pathology practice, I began performing comprehensive

Several years after I started my private speech pathology practice, I began performing comprehensive

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for

Recently I read a terrific article written in 2014 by

Recently I read a terrific article written in 2014 by

Need a L

Need a L