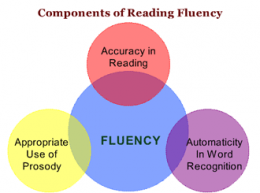

How many parents and professionals have experienced the following scenario? The child in question is reading very fluently (Landi & Ryherd, 2017) but comprehending very little of what s/he is reading. Attempts at remediation follow (oftentimes without the administration of a comprehensive assessment) with a focus on reading texts and answering text-related questions. However, much to everyone’s dismay the problem persists and worsens over time. The child’s mental health suffers as a result since numerous studies show that reading deficits including dyslexia are associated with depression, anxiety, attention, as well as behavioral problems (Arnold et al., 2005; Knivsberg & Andreassen, 2008; Huc-Chabrolle, et al, 2010; Kempe, Gustafson, & Samuelsson, 2011; Boyes, et al, 2016; Livingston et al, 2018). Continue reading Comprehending Reading Comprehension

How many parents and professionals have experienced the following scenario? The child in question is reading very fluently (Landi & Ryherd, 2017) but comprehending very little of what s/he is reading. Attempts at remediation follow (oftentimes without the administration of a comprehensive assessment) with a focus on reading texts and answering text-related questions. However, much to everyone’s dismay the problem persists and worsens over time. The child’s mental health suffers as a result since numerous studies show that reading deficits including dyslexia are associated with depression, anxiety, attention, as well as behavioral problems (Arnold et al., 2005; Knivsberg & Andreassen, 2008; Huc-Chabrolle, et al, 2010; Kempe, Gustafson, & Samuelsson, 2011; Boyes, et al, 2016; Livingston et al, 2018). Continue reading Comprehending Reading Comprehension

Category: Phonological Awareness

But is this the Best Practice Recommendation?

Those of you familiar with my blog, know that a number of my posts take on a form of extended responses to posts and comments on social media which deal with certain questionable speech pathology trends and ongoing issues (e.g., controversial diagnostic labels, questionable recommendations, non-evidence based practices, etc.). So, today, I’d like to talk about sweeping general recommendations as pertaining to literacy interventions. Continue reading But is this the Best Practice Recommendation?

Those of you familiar with my blog, know that a number of my posts take on a form of extended responses to posts and comments on social media which deal with certain questionable speech pathology trends and ongoing issues (e.g., controversial diagnostic labels, questionable recommendations, non-evidence based practices, etc.). So, today, I’d like to talk about sweeping general recommendations as pertaining to literacy interventions. Continue reading But is this the Best Practice Recommendation?

Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Karma Wilson’s “Bear” Books

In my previous posts, I’ve shared my thoughts about picture books being an excellent source of materials for assessment and treatment purposes. They can serve as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages and intellectual abilities, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are also incredibly effective treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Karma Wilson’s “Bear” Books

In my previous posts, I’ve shared my thoughts about picture books being an excellent source of materials for assessment and treatment purposes. They can serve as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages and intellectual abilities, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are also incredibly effective treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Karma Wilson’s “Bear” Books

Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Because the children I assess, often require supplementary reading instruction services, many parents frequently ask me how they can best determine if a reading specialist has the right experience to help their child learn how to read. So today’s blog post describes what type of knowledge reading specialists ought to possess and what type of questions parents (and other professionals) can ask them in order to determine their approaches to treating literacy-related difficulties of struggling learners. Continue reading Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Because the children I assess, often require supplementary reading instruction services, many parents frequently ask me how they can best determine if a reading specialist has the right experience to help their child learn how to read. So today’s blog post describes what type of knowledge reading specialists ought to possess and what type of questions parents (and other professionals) can ask them in order to determine their approaches to treating literacy-related difficulties of struggling learners. Continue reading Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Free Literacy Resources for Parents and Professionals

SLPs are constantly on the lookout for good quality affordable materials in the area of literacy. However, what many clinicians may not realize is that there are massive amounts of FREE evidence-based literacy-related resources available online for their use. These materials can be easily adapted or implemented as is, by parents, teachers, speech-language pathologists, as well as other literacy-focused professionals (e.g., tutors, etc.).

SLPs are constantly on the lookout for good quality affordable materials in the area of literacy. However, what many clinicians may not realize is that there are massive amounts of FREE evidence-based literacy-related resources available online for their use. These materials can be easily adapted or implemented as is, by parents, teachers, speech-language pathologists, as well as other literacy-focused professionals (e.g., tutors, etc.).

Below, I have compiled a rather modest list of my preferred resources (including a few articles) for children aged Pre-K-12 grade pertaining to the following literacy-related areas: Continue reading Free Literacy Resources for Parents and Professionals

Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

Picture books are absolutely wonderful for both assessment and treatment purposes! They are terrific as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are amazing treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

Picture books are absolutely wonderful for both assessment and treatment purposes! They are terrific as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are amazing treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

What Should be Driving Our Treatment?

Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?”

Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?”

Of course, the answer is never that simple. Just because a child has a diagnosis of a social communication disorder, word-finding deficits, or a reading disability does not automatically indicate to the treating clinician, which ‘cookie cutter’ materials and programs are best suited for the child in question. Only a profile of strengths and needs based on a comprehensive language and literacy testing can address this in an adequate and targeted manner.

To illustrate, reading intervention is a much debated and controversial topic nowadays. Everywhere you turn there’s a barrage of advice for clinicians and parents regarding which program/approach to use. Barton, Wilson, OG… the well-intentioned advice just keeps on coming. The problem is that without knowing the child’s specific deficit areas, the application of the above approaches is quite frankly … pointless.

There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader?

There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader?

Let’s a take a look at an example, below. It’s the CTOPP-2 results of a 7-6-year-old female with a documented history of extensive reading difficulties and a significant family history of reading disabilities in the family.

Results of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing-2 (CTOPP-2)

| Subtests | Scaled Scores | Percentile Ranks | Description |

| Elision (EL) | 7 | 16 | Below Average |

| Blending Words (BW) | 13 | 84 | Above Average |

| Phoneme Isolation (PI) | 6 | 9 | Below Average |

| Memory for Digits (MD) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Nonword Repetition (NR) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Rapid Digit Naming (RD) | 10 | 50 | Average |

| Rapid Letter Naming (RL) | 11 | 63 | Average |

| Blending Nonwords (BN) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Segmenting Nonwords (SN) | 8 | 25 | Average |

However, the results of her CTOPP-2 testing clearly indicate that phonological awareness, despite two areas of mild weaknesses, is not really a significant problem for this child. So let’s look at the student’s reading fluency results.

Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

So now we know that despite quite decent phonological awareness abilities, this student presents with quite poor sound-letter correspondence skills and will definitely benefit from explicit phonics instruction addressing the above deficit areas. But that is only the beginning! By looking at the analysis of specific misreadings we next need to determine what other literacy areas need to be addressed. For the sake of brevity, I can specify that further analysis of this child reading abilities revealed that reading comprehension, orthographic knowledge, as well as morphological awareness were definitely areas that also required targeted remediation. The assessment also revealed that the child presented with poor spelling and writing abilities, which also needed to be addressed in the context of therapy.

Now, what if I also told you that this child had already been receiving private, Orton-Gillingham reading instruction for a period of 2 years, 1x per week, at the time the above assessment took place? Would you change your mind about the program in question?

Well, the answer is again not so simple! OG is a fine program, but as you can see from the above example it has definite limitations and is not an exclusive fit for this child, or for any child for that matter. Furthermore, a solidly-trained in literacy clinician DOES NOT need to rely on just one program to address literacy deficits. They simply need solid knowledge of typical and atypical language and literacy development/milestones and know how to create a targeted treatment hierarchy in order to deliver effective intervention services. But for that, they need to first, thoughtfully, construct assessment-based treatment goals by carefully taking into the consideration the child’s strengths and needs.

So let’s stop asking which approach/program we should use and start asking about the child’s profile of strengths and needs in order to create accurate language and literacy goals based on solid evidence and scientifically-guided treatment practices.

Helpful Resources Pertaining to Reading:

- Earle, G. A., Sayeski, K. L (2017) Systematic Instruction in Phoneme-Grapheme Correspondence for Students With Reading Disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic. Vol. 52(5) 262–269

- The Florida Center for Reading Research (FCRR)

- Hasbrouck, J. & Tindal, G. A. (2006). Oral reading fluency norms: A valuable assessment tool for reading teachers. The Reading Teacher. 59(7), 636-644.

- O’Connor, R (2017) Reading Fluency and Students With Reading Disabilities: How Fast Is Fast Enough to Promote Reading Comprehension? Journal of Learning Disabilities

- Tolman, C (2005) Working Smarter, Not Harder: What Teachers of Reading Need to Know and Be Able to Teach IDA Perspectives pp. 15-23.

- Toste et al (2016) Reading Big Words: Instructional Practices to Promote Multisyllabic Word Reading Fluency Intervention in School and Clinic pp. 1–9

- Zipoli, R (2017) Unraveling-Difficult-Sentences: Strategies to Support Reading Comprehension. Intervention in School and Clinic, Vol. 52(4) 218–227. Intervention in School and Clinic, Vol. 52(4) 218–227

New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

September is quickly approaching and school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) are preparing to go back to work. Many of them are looking to update their arsenal of speech and language materials for the upcoming academic school year.

With that in mind, I wanted to update my readers regarding all the new products I have recently created with a focus on assessment and treatment in speech language pathology. Continue reading New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

Phonological Awareness Screening App Review: ProPA

Summer is in full swing and for many SLPs that means a welcome break from work. However, for me, it’s business as usual, since my program is year around, and we have just started our extended school year program.

Summer is in full swing and for many SLPs that means a welcome break from work. However, for me, it’s business as usual, since my program is year around, and we have just started our extended school year program.

Of course, even my program is a bit light on activities during the summer. There are lots of field trips, creative and imaginative play, as well as less focus on academics as compared to during the school year. However, I’m also highly cognizant of summer learning loss, which is the phenomena characterized by the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of summer holidays.

According to Cooper et al, 1996, while generally, typical students lose about one month of learning, there is actually a significant degree of variability of loss based on SES. According to Cooper’s study, low-income students lose approximately two months of achievement. Furthermore, ethnic minorities, twice-exceptional students (2xE), as well as students with language disorders tend to be disproportionately affected (Graham et al, 2011; Kim & Guryan, 2010; Kim, 2004). Finally, it is important to note that according to research, summer loss is particularly prominent in the area of literacy (Graham et al, 2011).

So this summer I have been busy screening the phonological awareness abilities (PA) of an influx of new students (our program enrolls quite a few students during the ESY), as well as rescreening PA abilities of students already on my caseload, who have been receiving services in this area for the past few months.

Why do I intensively focus on phonological awareness (PA)? Because PA is a precursor to emergent reading. It helps children to manipulate sounds in words (see Age of Aquisition of PA Skills). Children need to attain PA mastery (along with a host of a few literacy-related skills) in order to become good readers.

When children exhibit poor PA skills for their age it is a red flag for reading disabilities. Thus it is very important to assess the child’s PA abilities in order to determine their proficiency in this area.

While there are a number of comprehensive tests available in this area, for the purposes of my screening I prefer to use the ProPA app by Smarty Ears.

The Profile of Phonological Awareness (Pro-PA) is an informal phonological awareness screening. According to the developers on average it takes approximately 10 to 20 minutes to administer based on the child’s age and skill levels. In my particular setting (outpatient school based in a psychiatric hospital) it takes approximately 30 minutes to administer to students on the individual basis. It is by no means a comprehensive tool such as the CTOPP-2 or the PAT-2, as there are not enough trials, complexity or PA categories to qualify for a full-blown informal assessment. However, it is a highly useful measure for a quick determination of the students’ strengths and weaknesses with respect to their phonological awareness abilities. Given its current retail price of $29.99 on iTunes, it is a relatively affordable phonological awareness screening option, as the app allows its users to store data, and generates a two-page report at the completion of the screening.

The Pro-PA assesses six different skill areas:

- Rhyming

- Identification

- Production

- Blending

- Syllables

- Sounds

- Sound Isolation

- Initial

- Final

- Medial

- Segmentation

- Words in sentences

- Syllables in words

- Sounds in words

- Words with consonant clusters

- Deletion

- Syllables

- Sounds

- Words with consonant clusters

- Substitution

- Sounds in initial position of words

- Sounds in final position of words

After the completion of the screening, the app generates a two-page report which describes the students’ abilities as:

After the completion of the screening, the app generates a two-page report which describes the students’ abilities as:

- Achieved (80%+ accuracy)

- Not achieved (0-50% accuracy)

- Emerging (~50-79% accuracy)

The above is perfect for quickly tracking progress or for generating phonological awareness goals to target the students’ phonological awareness weaknesses. While the report can certainly be provided as an attachment to parents and teachers, I usually tend to summarize its findings in my own reports for the purpose of brevity. Below is one example of what that looks like:

The Profile of Phonological Awareness (Pro-PA), an informal phonological awareness screening was administered to “Justine” in May 2017 to further determine the extent of her phonological awareness strengths and weaknesses.

The Profile of Phonological Awareness (Pro-PA), an informal phonological awareness screening was administered to “Justine” in May 2017 to further determine the extent of her phonological awareness strengths and weaknesses.

On the Pro-PA, “Justine” evidenced strengths (80-100% accuracy) in the areas of rhyme identification, initial and final sound isolation in words, syllable segmentation, as well as substitution of sounds in initial position in words.

She also evidenced emerging abilities (~60-66% accuracy) in the areas of syllable and sound blending in words, as well as sound segmentation in CVC words,

However, Pro-PA assessment also revealed weaknesses (inability to perform) in the areas of: rhyme production, isolation of medial sounds in words, segmentation of words, segmentation of sounds in words with consonant blends,deletion of first sounds, consonant clusters, as well as substitution of sounds in final position in words. Continuation of therapeutic intervention is recommended in order to improve “Justine’s” abilities in these phonological awareness areas.

Now you know how I quickly screen and rescreen my students’ phonological awareness abilities, I’d love to hear from you! What screening instruments are you using (free or paid) to assess your students’ phonological awareness abilities? Do you feel that they are more or less comprehensive/convenient than ProPA?

References:

- Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J., & Greathouse, S. (1996). “The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: A narrative and meta analytic review.” Review of Educational Research, 66, 227–268.

- Graham, A., McNamara, J. K., & Van Lankveld, J. (2011). Closing the summer learning gap for vulnerable learners: An exploratory study of a summer literacy programme for kindergarten children at-risk for reading difficulties. Early Child Development and Care, 181, 575–585.

- Kim, J. S. (2004). Summer reading and the ethnic achievement gap. Journal of Education for Students Placed

at Risk, 9, 169–188. - Kim, J.,S. & Guryan, J. (2010). The efficacy of a voluntary summer book reading intervention for low-income Latino children from language minority families. Journal of

Educational Psychology, 102(1), 20-31

Treatment of Children with “APD”: What SLPs Need to Know

In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

More and more studies in the fields of audiology and speech-language pathology began confirming the lack of validity of APD as a standalone (or useful) diagnosis. To illustrate, in June 2015, the American Journal of Audiology published an article by David DeBonis entitled: “It Is Time to Rethink Central Auditory Processing Disorder Protocols for School-Aged Children.” In this article, DeBonis pointed out numerous inconsistencies involved in APD testing and concluded that “routine use of APD test protocols cannot be supported” and that [APD] “intervention needs to be contextualized and functional” (DeBonis, 2015, p. 124) Continue reading Treatment of Children with “APD”: What SLPs Need to Know