Several years ago I wrote a post about how to perform clinical reading assessments of adolescent students. Today I am writing a follow-up post with a focus on the clinical reading assessment of elementary-aged students. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 2-7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling elementary-aged readers. Continue reading Clinical Assessment of Reading Abilities of Elementary Aged Children

Category: Report Writing Tips

Neuropsychological or Language/Literacy: Which Assessment is Right for My Child?

![]() Several years ago I began blogging on the subject of independent assessments in speech pathology. First, I wrote a post entitled “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“, in which I used 4 different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Then I wrote about: “What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?” in order to elucidate on what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading Neuropsychological or Language/Literacy: Which Assessment is Right for My Child?

Several years ago I began blogging on the subject of independent assessments in speech pathology. First, I wrote a post entitled “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“, in which I used 4 different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Then I wrote about: “What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?” in order to elucidate on what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading Neuropsychological or Language/Literacy: Which Assessment is Right for My Child?

Test Review: Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs)

Today due to popular demand I am reviewing the Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs) for children and young adults ages 7 – 18, developed by the Lavi Institute and sold by WPS Publishing. Readers of this blog are familiar with the fact that I specialize in working with children diagnosed with psychiatric impairments and behavioral and emotional difficulties. They are also aware that I am constantly on the lookout for good quality social communication assessments due to a notorious dearth of good quality instruments in this area of language. Continue reading Test Review: Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs)

Today due to popular demand I am reviewing the Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs) for children and young adults ages 7 – 18, developed by the Lavi Institute and sold by WPS Publishing. Readers of this blog are familiar with the fact that I specialize in working with children diagnosed with psychiatric impairments and behavioral and emotional difficulties. They are also aware that I am constantly on the lookout for good quality social communication assessments due to a notorious dearth of good quality instruments in this area of language. Continue reading Test Review: Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs)

Editable Report Template and Tutorial for the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy

Today I am introducing my newest report template for the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy.

This 16-page fully editable report template discusses the testing results and includes the following components: Continue reading Editable Report Template and Tutorial for the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy

New Additions to My Comprehensive Report Tutorials and Templates

I have previously written regarding my line of products on the topic of: “Comprehensive Report Tutorials“. I had already added a number of editable comprehensive report templates to my online store.

These templates summarize popular speech-language pathology tests with meticulous detail. Each editable template will contain:

- Formal testing results breakdown in the form of a table

- A detailed overview of each subtest including a variety of hypotheses behind the student errors

- Summary of the students perceived deficits on the test and their correlation with language/literacy based deficits

- Long-term goals and detailed short-term’s objectives

Below is a select list of templates which are already available:

- Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5: Metalinguistics

- Listening Comprehension Tests (Elementary and adolescent versions)

- WORD Tests (Elementary and adolescent versions)

- Tests of Problem Solving (Elementary and Adolescent versions)

- Social Language Development Tests (Elementary and Adolescent versions)

- Executive Functions Test- Elementary

- Tests of Reading Comprehension

- Tests of Written Expression

- Comprehensive Tests of Phonological Processing

Available templates to date:

- TILLS Report Template

- SLDTE Report Template

- SLDTA Report Template

- CELF-5M Report Template

- TOPS-3 Report Template

- TOPS-2 Report Template

Continue reading New Additions to My Comprehensive Report Tutorials and Templates

What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?

Three years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“. In it, I used 4 very different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Today I would like to expound more on that post in order to explain, what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?

Three years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know“. In it, I used 4 very different scenarios to illustrate the importance of comprehensive language evaluations for children with subtle language and learning needs. Today I would like to expound more on that post in order to explain, what actually constitutes a good independent comprehensive assessment. Continue reading What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?

Clinical Assessment of Elementary-Aged Students Writing Abilities : Suggestions for SLPs

Recently I wrote a blog post regarding how SLPs can qualitatively assess writing abilities of adolescent learners. Today due to popular demand, I am offering suggestions regarding how SLPs can assess writing abilities of early-elementary-aged students with suspected learning and literacy deficits. For the purpose of this post, I will focus on assessing writing of second-grade students since by second-grade students are expected to begin producing simple written compositions several sentences in length (CCSS).

Recently I wrote a blog post regarding how SLPs can qualitatively assess writing abilities of adolescent learners. Today due to popular demand, I am offering suggestions regarding how SLPs can assess writing abilities of early-elementary-aged students with suspected learning and literacy deficits. For the purpose of this post, I will focus on assessing writing of second-grade students since by second-grade students are expected to begin producing simple written compositions several sentences in length (CCSS).

So how can we analyze the writing samples of young learners? For starters, it is important to know what the typical writing expectations look like for 2nd-grade students. Here’s is a sampling of typical expectations for second graders as per several sources (e.g., CCSS, Reading Rockets, Time4Writing, etc.)

- With respect to penmanship, students are expected to write legibly.

- With respect to grammar, students are expected to identify and correctly use basic parts of speech such as nouns and verbs.

- With respect to sentence structure students are expected to distinguish between complete and incomplete sentences as well as use correct subject/verb/noun/pronoun agreements and correct verb tenses in simple and compound sentences.

- With respect to punctuation, students are expected to use periods correctly at the end of sentences. They are expected to use commas in sentences with dates and items in a series.

- With respect to capitalization, students are expected to capitalize proper nouns, words at the beginning of sentences, letter salutations, months and days of the week, as well as titles and initials of people.

- With respect to spelling, students are expected to spell CVC (e.g., tap), CVCe (e.g., tape), as well as CCVC words (e.g., trap), high frequency regular and irregular spelled words (e.g., were, said, why, etc), basic inflectional endings (e.g., –ed, -ing, -s, etc), as well as to recognize select orthographic patterns and rules (e.g., when to spell /k/ or /c/ in CVC and CVCe word, how to drop one vowel (e.g., /y/) and replace it with another /i/, etc.)

Now let’s apply the above expectations to a writing sample of a 2nd-grade student whose parents are concerned with her writing abilities in addition to other language and learning concerns. This student was provided with a typical second grade writing prompt: “Imagine you are going to the North Pole. How are you going to get there? What would you bring with you? You have 15 minutes to write your story. Please make your story at least 4 sentences long.”

Now let’s apply the above expectations to a writing sample of a 2nd-grade student whose parents are concerned with her writing abilities in addition to other language and learning concerns. This student was provided with a typical second grade writing prompt: “Imagine you are going to the North Pole. How are you going to get there? What would you bring with you? You have 15 minutes to write your story. Please make your story at least 4 sentences long.”

The following is the transcribed story produced by her. “I am going in the north pole. I am going to bring food my mom toy’s stoft (stuffed) animals. I am so icsited (excited). So we are going in a box. We are going to go done (down) the stars (stairs) with the box and wate (wait) intile (until) the male (mail) is hear (here).”

Analysis: The student’s written composition content (thought formulation and elaboration) was judged to be impaired for her grade level. According to the CCSS, 2d grade students are expected to ‘”write narratives in which recount a well-elaborated event or short sequence of events, include details to describe actions, thoughts, and feelings, use temporal words to signal event order, and provide a sense of closure.” However, the above narrative sample by no means satisfies this requirement. The student’s writing was excessively misspelled, as well as lacked organization and clarity of message. While portions of her narrative appropriately addressed the question with respect to whom and what she was going to bring on her travels, her narrative quickly lost coherence by her 4th sentence, when she wrote: “So we are going in a box” with further elaborations regarding what she meant by that sentence. Second-grade students are expected to engage in basic editing and revision of their work. This student only took four minutes to compose the above-written sample and as such had more than adequate amount of time to review the question as well as her response for spelling and punctuation errors as well as for clarity of message, which she did not do. Furthermore, despite being provided with a written prompt which contained the correct capitalization of a place: “North Pole”, the student was not observed to capitalize it in her writing, which indicates ongoing executive function difficulties with the respect to proofreading and attention to details.

Impressions: Clinical assessment of the student’s writing revealed difficulties in the areas of spelling, capitalization, message clarity as well as lack of basic proofreading and editing, which require therapeutic intervention.

Now let us select a few writing goals for this student.

Now let us select a few writing goals for this student.

Long-Term Goals: Student will improve her writing abilities for academic purposes.

- Short-Term Goals

- Student will label parts of speech (e.g., adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, etc.) in compound sentences.

- Student will use declarative and interrogative sentence types for story composition purposes

- Student will correctly use past, present, and future verb tenses during writing tasks.

- Student will use basic punctuation at the sentence level (e.g., commas, periods, and apostrophes in singular possessives, etc.).

- Student will use basic capitalization at the sentence level (e.g., capitalize proper nouns, words at the beginning of sentences, months and days of the week, etc.).

- Student will proofread her work via reading aloud for clarity

- Student will edit her work for correct grammar, punctuation, and capitalization

Notice the above does not contain any spelling goals. That is because given the complexity of her spelling profile I prefer to tackle her spelling needs in a separate post, which discusses spelling development, assessment, as well as intervention recommendations for students with spelling deficits.

There you have it. A quick and easy qualitative writing assessment for elementary-aged students which can help determine the extent of the student’s writing difficulties as well as establish a few writing remediation targets for intervention purposes.

Using a different type of writing assessment with your students? Please share the details below so we can all benefit from each others knowledge of assessment strategies.

New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

September is quickly approaching and school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) are preparing to go back to work. Many of them are looking to update their arsenal of speech and language materials for the upcoming academic school year.

With that in mind, I wanted to update my readers regarding all the new products I have recently created with a focus on assessment and treatment in speech language pathology. Continue reading New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

Adolescent Assessments in Action: Clinical Reading Evaluation

In the past several years, due to an influx of adolescent students with language and learning difficulties on my caseload, I have begun to research in depth aspects of adolescent language development, assessment, and intervention.

In the past several years, due to an influx of adolescent students with language and learning difficulties on my caseload, I have begun to research in depth aspects of adolescent language development, assessment, and intervention.

While a number of standardized assessments are available to test various components of adolescent language from syntax and semantics to problem-solving and social communication, etc., in my experience with this age group, frequently, clinical assessments (vs. the standardized tests), do a far better job of teasing out language difficulties in adolescents.

Today I wanted to write about the importance of performing a clinical reading assessment as part of select* adolescent language and literacy evaluations.

There are a number of standardized tests on the market, which presently assess reading. However, not all of them by far are as functional as many clinicians would like them to be. To illustrate, one popular reading assessment is the Gray Oral Reading Tests-5 (GORT-5). It assesses the student’s rate, accuracy, fluency, and comprehension abilities. While it’s a useful test to possess in one’s assessment toolbox, it is not without its limitations. In my experience assessing adolescent students with literacy deficits, many can pass this test with average scores, yet still present with pervasive reading comprehension difficulties in the school setting. As such, as part of the assessment process, I like to administer clinical reading assessments to students who pass the standardized reading tests (e.g., GORT-5), in order to ensure that the student does not possess any reading deficits at the grade text level.

So how do I clinically assess the reading abilities of struggling adolescent learners?

First, I select a one-page long grade level/below grade-level text (for very impaired readers). I ask the student to read the text, and I time the first minute of their reading in order to analyze their oral reading fluency or words correctly read per minute (wcpm).

For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 5 – 7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling adolescent readers. In some cases using a below grade level text allows me to starkly illustrate the extent of the student’s reading difficulties. Below is an example of one of such a clinical reading assessments in action.

For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 5 – 7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling adolescent readers. In some cases using a below grade level text allows me to starkly illustrate the extent of the student’s reading difficulties. Below is an example of one of such a clinical reading assessments in action.

CLINICAL READING ASSESSMENT: 8th Grade Male

A clinical reading assessment was administered to TS, a 15-5-year-old male, on a supplementary basis in order to further analyze his reading abilities. Given the fact that TS was reported to present with grade-level reading difficulties, the examiner provided TS a 7th-grade text by Continental Press. TS was asked to read aloud the 7 paragraph long text, and then answer factual and inferential questions, summarize the presented information, define select context embedded vocabulary words as well as draw conclusions based on the presented text. (Please note that in order to protect the client’s privacy some portions of the below assessment questions and responses were changed to be deliberately vague).

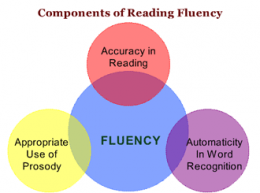

Reading Fluency: TS’s reading fluency (automaticity, prosody, accuracy and speed, expression, intonation, and phrasing) during the reading task was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody.

Reading Fluency: TS’s reading fluency (automaticity, prosody, accuracy and speed, expression, intonation, and phrasing) during the reading task was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody.

With respect to specific errors, TS was observed to occasionally add word fillers to text (e.g., and, a, etc.), change morphological endings of select words (e.g., read /elasticity/ as /elastic/, etc.) as well as substitute similar looking words (e.g., from/for; those/these, etc.) during reading. He occasionally placed stress on the first vs. second syllable in disyllabic words, which resulted in distorted word productions (e.g., products, residual, upward, etc.), as well as inserted extra words into text (e.g., read: “until pressure inside the earth starts to build again” as “until pressure inside the earth starts to build up again”). He also began reading a number of his sentences with false starts (e.g., started reading the word “drinking” as ‘drunk’, etc.) and as a result was observed to make a number of self-corrections during reading.

During reading, TS demonstrated adequate tracking movements for text scanning as well as use of context to aid his decoding. For example, TS was observed to read the phonetic spelling of select unfamiliar words in parenthesis (e.g., equilibrium) and then read them correctly in subsequent sentences. However, he exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies and did not always self-correct misread words; dispute the fact that they did not always make sense in the context of the read sentences.

TS’s oral reading rate during today’s reading was judged to be reduced for his age/grade levels. An average 8th grader is expected to have an oral reading rate between 145 and 160 words per minute. In contrast, TS was only able to read 114 words per minute. However, it is important to note that recent research on reading fluency has indicated that as early as by 4th grade reading faster than 90 wcpm will not generate increases in comprehension for struggling readers. Consequently, TS’s current reading rate of off 114 words per minute was judged to be adequate for reading purposes. Furthermore, given the fact that TS’s reading comprehension is already compromised at this rate (see below for further details) rather than making a recommendation to increase his reading rate further, it is instead recommended that intervention focuses on slowing TS’s rate via relevant strategies as well as improving his reading comprehension abilities. Strategies should focus on increasing his opportunities to learn domain knowledge via use of informational texts; purposeful selection of texts to promote knowledge acquisition and gain of expertise in different domains; teaching morphemic as well as semantic feature analyses (to expand upon already robust vocabulary), increasing discourse and critical thinking with respect to informational text, as well as use of graphic organizers to teach text structure and conceptual frameworks.

Verbal Text Summary: TS’s text summary following his reading was very abbreviated, simplified, and confusing. When asked: “What was this text about?” Rather than stating the main idea, TS nonspecifically provided several vague details and was unable to elaborate further. When asked: “Do you think you can summarize this story for me from beginning to the end?” TS produced the two disjointed statements, which did not adequately address the presented question When asked: “What is the main idea of this text.” TS vaguely responded: “Science,” which was the broad topic rather than the main idea of the story.

Text Vocabulary Comprehension:

Text Vocabulary Comprehension:

After that, TS was asked a number of questions regarding story vocabulary. The first word presented to him was “equilibrium”. When asked: “What does ‘equilibrium’ mean?” TS first incorrectly responded: “temperature”. Then when prompted: “Anything else?” TS correctly replied: “balance.” He was then asked to provide some examples of how nature leans towards equilibrium from the story. TS nonspecifically produced: “Ah, gravity.” When asked to explain how gravity contributes to the process of equilibrium TS again nonspecifically replied: “gravity is part of the planet”, and could not elaborate further. TS was then asked to define another word from the text provided to him in a sentence: “Scientists believe that this is residual heat remaining from the beginnings of the solar system.” What is the meaning of the word: “residual?” TS correctly identified: “remaining.” Then the examiner asked him to define the term found in the last paragraph of the text: “What is thermal equilibrium?” TS nonspecifically responded: “a balance of temperature”, and was unable to elaborate further.

Reading Comprehension (with/out text access):

TS was also asked to respond to a number of factual text questions without the benefit of visual support. However, he presented with significant difficulty recalling text details. TS was asked: When asked, “Why did this story mention ____? What did they have to do with ____?” TS responded nonspecifically, “______.” When prompted to tell more, TS produced a rambling response which did not adequately address the presented question. When asked: “Why did the text talk about bungee jumpers? How are they connected to it?” TS stated, “I am ah, not sure really.”

Finally, TS was provided with a brief worksheet which accompanied the text and asked to complete it given the benefit of written support. While TS’s performance on this task was better, he still achieved only 66% accuracy and was only able to answer 4 out of 6 questions correctly. On this task, TS presented with difficulty identifying the main idea of the third paragraph, even after being provided with multiple choice answers. He also presented with difficulty correctly responding to the question pertaining to the meaning of the last paragraph.

Impressions: Clinical below grade-level reading comprehension assessment reading revealed that TS presents with a number of reading related difficulties. TS’s reading fluency was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody. TS’s understanding as well as his verbal summary of the presented text was immature for his age and was characterized by impaired gestalt processing of information resulting in an ineffective and confusing summarization. While TS’s text-based vocabulary knowledge was deemed to be grossly adequate for his age, his reading comprehension abilities were judged to be impaired for his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve TS’s reading abilities. (See Impressions and Recommendations sections for further details).

Impressions: Clinical below grade-level reading comprehension assessment reading revealed that TS presents with a number of reading related difficulties. TS’s reading fluency was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody. TS’s understanding as well as his verbal summary of the presented text was immature for his age and was characterized by impaired gestalt processing of information resulting in an ineffective and confusing summarization. While TS’s text-based vocabulary knowledge was deemed to be grossly adequate for his age, his reading comprehension abilities were judged to be impaired for his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve TS’s reading abilities. (See Impressions and Recommendations sections for further details).

There you have it! This is just one of many different types of informal reading assessments, which I occasionally conduct with adolescents who attain average scores on reading fluency and reading comprehension tests such as the GORT-5 or the Test of Reading Comprehension -4 (TORC-4), but still present with pervasive reading difficulties working with grade level text.

You can find more information on the topic of adolescent assessments (including other comprehensive informal write-up examples) in this recently developed product entitled: Assessment of Adolescents with Language and Literacy Impairments in Speech Language Pathology currently available in my online store.

What about you? What type of informal tasks and materials are you using to assess your adolescent students’ reading abilities and why do you like using them?

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Adolescent Assessment Resources:

- Assessment of Adolescents with Language and Literacy Impairments in Speech Language Pathology

- Comprehensive Literacy Checklist For School-Aged Children

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents

Early Intervention Evaluations PART III: Assessing Children Under 2 Years of Age

In this post, I am continuing my series of articles on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first installment in this series offered suggestions regarding what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, while my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders.

In this post, I am continuing my series of articles on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first installment in this series offered suggestions regarding what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, while my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders.

Today, I’d like to describe what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age. As I mentioned in my previous posts, the bulk of children I assess under the age of 3, are typically aged 30 months or older. However, a relatively small number of children are brought in for an assessment around an 18-month mark, which is the age group that I would like to discuss today.

Typically, these children are brought in due to a lack of or minimal speech-language production. Interestingly enough, based on the feedback of colleagues, this group is surprisingly hard to report on. While all SLPs will readily state that 18-month-old children are expected to have a verbal vocabulary of at least 50 words and begin to combine them into two-word utterances (e.g., ‘daddy eat’). When prompted: “Well, what else should my child be capable of?” many SLPs draw a blank regarding what else to say to parents on the spot.

As mentioned in my previous post on assessment of children under 3, the following sections should be an integral part of every early intervention speech-language assessment:

As mentioned in my previous post on assessment of children under 3, the following sections should be an integral part of every early intervention speech-language assessment:

- Background History

- Language Development and Use (Free Questionnaires)

- Adaptive Behavior

- Play Assessment (Westby, 2000) (Westby Play Scale-Revised Link)

- Auditory Function

- Oral Motor Exam

- Feeding and Swallowing

- Vocal Parameters

- Fluency and Resonance

- Articulation and Phonology

- Phonetic inventory

- Phonotactic Repertoire

- Speech intelligibility

- Phonological Processes Analysis (Independent and Relational)

- Receptive Language

- Expressive Language

- Social Emotional Development

- Pragmatic Language

- Impressions

- Recommendations

- Suggested Therapy Goals

- References (if pertinent to a particular report)

In my two previous posts, I’ve also offered examples of select section write-ups (e.g., receptive, expressive phonology, etc.). Below a would like to offer a few more for this age group. Below is an example of a write-up on an 18-month-old bilingual child with a very limited verbal output.

RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE:

L’s receptive language skills were solid at 8 months of age (as per clinical observations and REEL-3 findings) which is significantly below age-expectancy for a child her age (18 months). During the assessment L received credit for appropriately reacting to prohibitive verbalizations (e.g., “No”, “Stop”), attending to speaker when her name was spoken, performing a routine activity upon request (when combined with gestures), looking at familiar object when named, finding the aforementioned familiar object when not in sight, as well as pointing to select body parts on Mrs. L and self (though identification on self was limited). L is also reported to be able to respond to yes/no questions by head nods and shakes.

However, during the assessment L was unable to consistently follow 1 and 2 step directions without gestural cues, understand and perform simple actions per clinician’s request, select objects from a group of 3-5 items given a verbal command, select familiar puzzle pieces from a visual field of 2 choices, understand simple ‘wh questions (e.g., “what?”, “where?”), point to objects or pictures when named, identify simple pictures of objects in book, or display the knowledge and understanding of age appropriate content, function and early concept words (in either Russian or English) as is appropriate for a child her age.

EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE and ARTICULATION

L’s expressive language skills were judged to be solid at 7 months of age (as per clinical observations and REEL-3 findings), which is significantly below age-expectancy for a child her age (18 months). L was observed to spontaneously use proto-imperative gestures (eye gaze, reaching, and leading [by hand]), vocalizations, as well waving for the following language functions: requesting, rejecting, regulating own environment as well as providing closure (waving goodbye).

L’s spontaneous vocalizations consisted primarily of reduplicated babbling (with a limited range of phonemes) which is significantly below age-expectancy for a child her age (see below for developmental norms). During the assessment, L was observed to frequently vocalize “da-da-da”. However, it was unclear whether she was vocalizing to request objects (in Russian “dai” means “give”) due to the fact that she was not observed to consistently vocalize the above solely when requesting items. Additionally, L was not observed to engage in reciprocal babbling or syllable/word imitation during today’s assessment, which is a concern for a child her age. When the examiner attempted to engage L in structured imitation tasks by offering and subsequently denying a toy of interest until L attempted to imitate the desired sound, L became easily frustrated and initiated tantrum behavior. During the assessment, L was not observed to imitate any new sounds trialed with her by the examiner.

During today’s assessment, L’s primary means of communication consisted of eye gaze, reaching, crying, gestures, as well as sound and syllable vocalizations. L’s phonetic inventory consisted of the following consonant sounds: plosives (/p/, /b/ as reported by Mrs. L), alveolars (/t/, /d/ as reported and observed), fricative (/v/ as observed), velar (/g/ as observed), as well as nasal (/n/, and /m/ as observed). L was also observed to produce two vowels /a/ and a pharyngeal /u/. L’s phonotactic repertoire was primarily restricted to reported CV(C-consonant; V-vowel) and VCV syllable shapes, which is significantly reduced for a child her age.

According to developmental norms, a child of L’s age (18 months) is expected to produce a wide variety of consonants (e.g., [b, d, m, n, h, w] in initial and [t, h, s] in final position of words) as well as most vowels. (Robb, & Bleile,(1994); Selby, Robb & Gilbert, 2000). During this time the child’s vocabulary size increases to 50+ words at which point children begin to combine these words to produce simple phrases and sentences (as per Russian and English developmental norms). Additionally, an, 18 months old child is expected to begin monitoring and repairing own utterances, adjusting speech to different listeners, as well as practicing sounds, words, and early sentences. (Clark, adapted by Owens, 2015)

Based on the above guidelines L’s receptive and expressive language, as well as articulation abilities, are judged to be significantly below age expectancy at this time. Speech and language therapy is strongly recommended in order to improve L’s speech and language skills.

Typically when the assessed young children exhibit very limited comprehension and expression, I tend to provide their caregivers with a list of developmental expectations for that specific age group (given the range of a few months) along with recommendations of communication facilitation. Below is an example of such a list, pulled a variety of resources.

Developmental Milestones expected of a 16-18 months old toddler:

Developmental Milestones expected of a 16-18 months old toddler:

Attention/Gaze:

- Make frequent spontaneous eye contact with adults during interactions

- Turn head to look towards the new voice, when another person begins to talk

- Make 3-point gaze shifts by 1. looking at a toy in hand, 2. then at an adult, 3. then back to the toy

- Make 4-point gaze shifts if more than one person is in the room – by looking from a toy in hand to one person, then the other person, then back to the toy,

- Spontaneously attend to book, activity for 2-3+ minutes without redirection

Reaching and Gestures:

- Show objects in hand to an adult (without actually giving them)

- Push away items that aren’t wanted

- Engage in give and take games when holding objects with an adult

- Imitate simple gestures such as clapping hands or waving bye-bye

- Hand an object to an adult to ask for help with it

- Shake head “no?”

Play Skills/Routines:

Play Skills/Routines:

- Attempt to actively explore toys (e.g., push or spin parts of toys, turn toys over, roll them back and forth)

- Repeat interesting actions with toys (e.g., make a toy produce an unusual noise, then attempt to make the noise again)

- Imitate simple play activities (adult bangs two blocks together, then child imitates)

- Use objects on daily basis (e.g., when given a spoon or cup the child attempts to feed himself. When putting on clothes the child begins to lift his arms in anticipation of a shirt going on.)

Receptive (Listening Skills):

- Consistently follow 1 and 2 step directions without gestural cues

- Understand and perform simple actions per request (“sit down” or “come here”) without gestures

- Select objects from a group of 3 items given a verbal command

- Select familiar puzzle pieces from a visual field of 2 choices

- Understand simple ‘wh questions (e.g., “what?”, “where?”)

- Point to objects or pictures when named

- Spontaneously and consistently identify simple pictures of objects in book

- Stop momentarily what he is doing if an adult says “no” in a firm voice

- Identify 2-3 common everyday objects or body parts when asked

Expressive (Speaking Skills):

- Produce a wide variety of consonants (e.g., [b, d, m, n, h, w] in initial and [t, h, s] in final position of words) as well as most vowels. (Robb, & Bleile,(1994); Selby, Robb & Gilbert, 2000).

- Have a vocabulary size nearing 50 words (e.g., 35-40)

- Imitate adult words or vocalizations

- Attempt to practice sounds and words (Clark, adapted by Owens, 2015)

- Appropriately label familiar objects (foods, toys, animals)

Materials to use with the child to promote language and play:

Materials to use with the child to promote language and play:

- Bubbles

- Cause and effect toys

- Toys with a variety of textures (soft toys, plastic toys, cardboard blocks, ridged balls)

- Toys with multiple actions

- Toys with special effects: lights, sounds, movement (push and go vehicles)

- Building and linking toys

- Toys with multiple parts

- Balls, cars and trucks, animals, dolls

- Puzzles

- Pop-up picture books

- Toys the child demonstrates an interest in (parents should advise)

Strategies:

- Reduce distractions (noise, clutter etc)

- Provide one on one interaction in a structured space (e.g., sitting at the play table or sitting on parent’s lap) to improve attention

- Offer favorite activities and toys of interest initially before branching out to new materials

- Offer favorite foods/toys as reinforcers to continue working

- Offer choices of two toys, then remove one toy and focus interaction with one toy of interest

- Try to prolong attention to toy for several minutes at a time

- Change activities frequently, HOWEVER, repeat same activities in cycles over and over again during home practice in order to solidify skills

- Label objects and actions in the child’s immediate environment

- Use brief but loud utterances (2-3 words not more) to gain attention and understanding

- Frequently repeat words in order to ensure understanding of what is said/expected of child

- Use combination of gestures, signs, words, and pictures to teach new concepts

- Do not force child to speak if he doesn’t want to rather attempt to facilitate production of gestures/sounds (e.g., use “hand over hand” to show child the desired gesture such as pointing/waving/motioning in order to reduce his/her frustration

- Use play activities as much as possible to improve child’s ability to follow directions and comprehend language

- Doll House (with Little People)

- Garage

- Farm, etc

Core vocabulary categories for listening and speaking:

Core vocabulary categories for listening and speaking:

- Favorite and familiar toys and objects

- Names of people in the child’s life as well as his own name

- Pets

- Favorite or familiar foods

- Clothing

- Body parts

- Names of daily activities and actions (go, fall, drink, eat, walk, wash, open)

- Recurrence (more)

- Names of places (bed, outside)

- Safety words (hot, no, stop, dangerous, hurt, don’t touch, yuck, wait)

- Condition words (boo-boo, sick/hurt, mad, happy)

- Early pronouns (me, mine)

- Social words (hi, bye, please, sorry)

- Early concepts: in, off, on, out, big, hot, one, up, down, yucky, wet, all done)

- Yes/no

Select References:

- Owens, R. E. (2015). Language development: An introduction (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Rescorla, L. (1989). The Language Development Survey: A screening tool for delayed language in toddlers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 587–599.

- Rescorla, L., Hadicke-Wiley, M., & Escarce, E. (1993). Epidemiological investigation of expressive language delay

at age two. First Language, 13, 5–22. - Robb, M. P., & Bleile, K. M. (1994). Consonant inventories of young children from 8 to 25 months. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 8, 295-320.

- Selby, J. C., Robb, M. P., & Gilbert, H. R. (2000). Normal vowel articulations between 15 and 36 months of age. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 14, 255-266.

Click HERE for the Early Intervention Evaluations PART IV: Assessing Pragmatic Abilities of Children Under 3

Stay Tuned for the next installment in this series:

- Early Intervention Evaluations PART V: Assessing Feeding and Swallowing in Children Under Two