Many of my students with Developmental Language Disorders (DLD) lack insight and have poorly developed metalinguistic (the ability to think about and discuss language) and metacognitive (think about and reflect upon own thinking) skills. This, of course, creates a significant challenge for them in both social and academic settings. Not only do they have a poorly developed inner dialogue for critical thinking purposes but they also because they present with significant self-monitoring and self-correcting challenges during speaking and reading tasks. Continue reading Have I Got This Right? Developing Self-Questioning to Improve Metacognitive and Metalinguistic Skills

Many of my students with Developmental Language Disorders (DLD) lack insight and have poorly developed metalinguistic (the ability to think about and discuss language) and metacognitive (think about and reflect upon own thinking) skills. This, of course, creates a significant challenge for them in both social and academic settings. Not only do they have a poorly developed inner dialogue for critical thinking purposes but they also because they present with significant self-monitoring and self-correcting challenges during speaking and reading tasks. Continue reading Have I Got This Right? Developing Self-Questioning to Improve Metacognitive and Metalinguistic Skills

Category: resource websites

Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Because the children I assess, often require supplementary reading instruction services, many parents frequently ask me how they can best determine if a reading specialist has the right experience to help their child learn how to read. So today’s blog post describes what type of knowledge reading specialists ought to possess and what type of questions parents (and other professionals) can ask them in order to determine their approaches to treating literacy-related difficulties of struggling learners. Continue reading Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Because the children I assess, often require supplementary reading instruction services, many parents frequently ask me how they can best determine if a reading specialist has the right experience to help their child learn how to read. So today’s blog post describes what type of knowledge reading specialists ought to possess and what type of questions parents (and other professionals) can ask them in order to determine their approaches to treating literacy-related difficulties of struggling learners. Continue reading Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

The end of the school year is almost near. Soon many of our clients with language and literacy difficulties will be going on summer vacation and enjoying their time outside of school. However, summer is not all fun and games. For children with learning needs, this is also a time of “learning loss”, or the loss of academic skills and knowledge over the course of the summer break. Students diagnosed with language and learning disabilities are at a particularly significant risk of greater learning loss than typically developing students. Continue reading Tips on Reducing ‘Summer Learning Loss’ in Children with Language/Literacy Disorders

Analyzing Narratives of School-Aged Children

As mentioned previously, for elicitation purposes, I frequently use the books recommended by the SALT Software website, which include: ‘Frog Where Are You?’ by Mercer Mayer, ‘Pookins Gets Her Way‘ and ‘A Porcupine Named Fluffy‘ by Helen Lester, as well as ‘Dr. DeSoto‘ by William Steig. Continue reading Analyzing Narratives of School-Aged Children

Creating a Comprehensive Speech Language Therapy Environment

So you’ve completed a thorough evaluation of your student’s speech and language abilities and are in the process of creating goals and objectives to target in sessions. The problem is that many of the students on our caseloads present with pervasive deficits in many areas of language.

So you’ve completed a thorough evaluation of your student’s speech and language abilities and are in the process of creating goals and objectives to target in sessions. The problem is that many of the students on our caseloads present with pervasive deficits in many areas of language.

While it’s perfectly acceptable to target just a few goals per session in order to collect good data, both research and clinical experience indicate that addressing goals comprehensively and thematically (the whole system or multiple goals at once from the areas of content, form, and use) via contextual language intervention vs. in isolation (small parts such as prepositions, pronouns, etc.) will bring about the quickest change and more permanent results.

So how can that be done? Well, for significantly language impaired students it’s very important to integrate semantic language components as well as verbal reasoning tasks into sessions no matter what type of language activity you are working on (such as listening comprehension, auditory processing, social inferencing and so on). The important part is to make sure that the complexity of the task is commensurate with the student’s level of abilities.

Let’s say you are working on a fall themed lesson plans which include topics such as apples and pumpkins. As you are working on targeting different language goals, just throw in a few extra components to the session and ask the child to make, produce, explain, list, describe, identify, or interpret:

- Associations (“We just read a book about pumpkin: What goes with a pumpkin?”)

- Synonyms (“It said the leaves felt rough, what’s another word for rough?”)

- Antonyms (“what is the opposite of rough?”)

- Attributes 5+ (category, function, location, appearance, accessory/necessity, composition) (“Pretend I don’t know what a pumpkin is, tell me everything you can think of about a pumpkin”)

- Multiple Meaning Words (“The word felt has two meanings, it could mean _____ and it could also mean _______”)

- Definitions (“what is a pumpkin”)

- Compare and Contrast (“How are pumpkin and apple alike? How are they different?”)

- Idiomatic expressions (“Do you know what the phrase turn into a pumpkin means?” )

Ask ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions in order to start teaching the student how to justify, rationalize, evaluate, and make judgments regarding presented information (“Why do you think we plant pumpkins in the spring and not in the fall?”)

Don’t forget the inferencing and predicting questions in order to further develop the client’s verbal reasoning abilities (“What do you think will happen if no one picks up the apples from the ground?)

If possible attempt to integrate components of social language into the session such as ask client to relate to a character in a story, interpret the character’s feelings (“How do you think the girl felt when her sisters made fun of her pumpkin?”), ideas and thoughts, or just read nonverbal social cues such as body language or facial expressions of characters in pictures.

Select materials which are both multipurpose and reusable as well as applicable to a variety of therapy goals. For example, let’s take a simple seasonal word wall such as the (free) Fall Word Wall from TPT by Pocketful of Centers. Print it out in color, cut out the word strips and note how many therapy activities you can target for articulation, language, fluency, literacy and phonological awareness, etc.

Language:

Practice Categorization skills via convergent and divergent naming activities: Name Fall words, Name Halloween/Thanksgiving Words, How many trees whose leaves change color can you name?, how many vegetables and fruits do we harvest in the fall? etc.

Practice naming Associations: what goes with a witch (broom), what goes with a squirrel (acorn), etc

Practice providing Attributes via naming category, function, location, parts, size, shape, color, composition, as well as accessory/necessity. For example, (I see a pumpkin. It’s a fruit/vegetable that you can plant, grow and eat. You find it on a farm. It’s round and orange and is the size of a ball. Inside the pumpkin are seeds. You can carve it and make a jack o lantern out of it).

Practice providing Definitions: Tell me what a skeleton is. Tell me what a scarecrow is.

Practice naming Similarities and Differences among semantically related items: How are pumpkin and apple alike? How are they different?

Practice explaining Multiple Meaning words: What are some meanings of the word bat, witch, clown, etc?

Practice Complex Sentence Formulation: what happens in the fall? Make up a sentence with the words scarecrow and unless, make up a sentence with the words skeleton and however, etc

Phonological Awareness:

Practice Rhyming words (you can do discrimination and production activities): cat/bat/ trick/leaf/ rake/moon

Practice Syllable and Phoneme Segmentation (I am going to say a word (e.g., leaf, corn, scarecrow, etc) and I want you to clap one time for each syllable or sound I say)

Practice Isolation of initial, medial, and final phonemes in words ( e.g., What is the beginning/final sound in apple, hay, pumpkin etc?) What is the middle sound in rake etc?

Practice Initial and Final Syllable and Phoneme Deletion in Words (Say spider! Now say it without the der, what do you have left? Say witch, now say it without the /ch/ what is left; say corn, now say it without the /n/, what is left?)

Articulation/Fluency:

Practice production of select sounds/consonant clusters that you are working on or just production at word or sentence levels with those clients who just need a little bit more work in therapy increasing their intelligibility or sentence fluency.

So next time you are targeting your goals, see how you can integrate some of these suggestions into your data collection and let me know whether or not you’ve felt that it has enhanced your therapy sessions.

Happy Speeching!

Helpful Resources:

- Creating Functional Therapy Plan

- Selecting Clinical Materials for Pediatric Therapy

- Vocabulary Development: Working With Disadvantaged Populations

- General Assessment and Treatment Start-Up Bundle

Back to School SLP Efficiency Bundles™

September is practically here and many speech language pathologists (SLPs) are looking to efficiently prepare for assessing and treating a variety of clients on their caseloads.

September is practically here and many speech language pathologists (SLPs) are looking to efficiently prepare for assessing and treating a variety of clients on their caseloads.

With that in mind, a few years ago I created SLP Efficiency Bundles™, which are materials highly useful for SLPs working with pediatric clients. These materials are organized by areas of focus for efficient and effective screening, assessment, and treatment of speech and language disorders.

A. General Assessment and Treatment Start-Up Bundle contains 5 downloads for general speech language assessment and treatment planning and includes:

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a Preschool Child

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a School-Aged Child

- Creating a Functional Therapy Plan: Therapy Goals & SOAP Note Documentation

- Selecting Clinical Materials for Pediatric Therapy

- Types and Levels of Cues and Prompts in Speech Language Therapy

B. The Checklists Bundle contains 7 checklists relevant to screening and assessment in speech language pathology

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a Preschool Child 3:00-6:11 years of age

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for a School-Aged Child 7:00-11:11 years of age

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents 12-18 years of age

- Language Processing Deficits (LPD) Checklist for School Aged Children 7:00-11:11 years of age

- Language Processing Deficits (LPD) Checklist for Preschool Children 3:00-6:11 years of age

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children 7:00-11:11 years of age

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children 3:00-6:11 years of age

C. Social Pragmatic Assessment and Treatment Bundle contains 6 downloads for social pragmatic assessment and treatment planning (from 18 months through school age) and includes:

- Recognizing the Warning Signs of Social Emotional Difficulties in Language Impaired Toddlers and Preschoolers

- Behavior Management Strategies for Speech Language Pathologists

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children

- Assessing Social Pragmatic Skills of School Aged Children

- Treatment of Social Pragmatic Deficits in School Aged Children

D. Multicultural Assessment and Treatment Bundle contains 2 downloads relevant to assessment and treatment of bilingual/multicultural children

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

E. Narrative Assessment Bundle contains 3 downloads relevant to narrative assessment

- Narrative Assessments of Preschool and School Aged Children

- Understanding Complex Sentences

- Vocabulary Development: Working with Disadvantaged Populations

F. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Assessment and Treatment Bundle contains 3 downloads relevant to FASD assessment and treatment

- Orofacial Observations of At-Risk Children

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: An Overview of Deficits

- Speech Language Assessment and Treatment of Children With Alcohol Related Disorders

G. Psychiatric Disorders Bundle contains 7 downloads relevant to language assessment and treatment in psychiatrically impaired children

- Recognizing the Warning Signs of Social Emotional Difficulties in Language Impaired Toddlers and Preschoolers

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children

- Assessing Social Skills in Children with Psychiatric Disturbances

- Improving Social Skills of Children with Psychiatric Disturbances

- Behavior Management Strategies for Speech Language Pathologists

- Differential Diagnosis Of ADHD In Speech Language Pathology

You can find these bundles on SALE in my online store by clicking on the individual bundle links above. You can also purchase these products individually in my online store by clicking HERE.

Early Intervention Evaluations PART I: Assessing 2.5 year olds

Today, I’d like to talk about speech and language assessments of children under three years of age. Namely, the quality of these assessments. Let me be frank, I am not happy with what I am seeing. Often times, when I receive a speech-language report on a child under three years of age, I am struck by how little functional information it contains about the child’s linguistic strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, conversations with parents often reveal that at best the examiner spent no more than half an hour or so playing with the child and performed very limited functional testing of their actual abilities. Instead, they interviewed the parent and based their report on parental feedback alone. Consequently, parents often end up with a report of very limited value, which does not contain any helpful information on how delayed is the child as compared to peers their age.

Today, I’d like to talk about speech and language assessments of children under three years of age. Namely, the quality of these assessments. Let me be frank, I am not happy with what I am seeing. Often times, when I receive a speech-language report on a child under three years of age, I am struck by how little functional information it contains about the child’s linguistic strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, conversations with parents often reveal that at best the examiner spent no more than half an hour or so playing with the child and performed very limited functional testing of their actual abilities. Instead, they interviewed the parent and based their report on parental feedback alone. Consequently, parents often end up with a report of very limited value, which does not contain any helpful information on how delayed is the child as compared to peers their age.

So today I like to talk about what information should such speech-language reports should contain. For the purpose of this particular post, I will choose a particular developmental age at which children at risk of language delay are often assessed by speech-language pathologists. Below you will find what information I typically like to include in these reports as well as developmental milestones for children 30 months or 2.5 years of age.

Why 30 months, you may ask? Well, there isn’t really any hard science to it. It’s just that I noticed that a significant percentage of parents who were already worried about their children’s speech-language abilities when they were younger, begin to act upon those worries as the child is nearing 3 years of age and their abilities are not improving or are not commensurate with other peers their age.

Why 30 months, you may ask? Well, there isn’t really any hard science to it. It’s just that I noticed that a significant percentage of parents who were already worried about their children’s speech-language abilities when they were younger, begin to act upon those worries as the child is nearing 3 years of age and their abilities are not improving or are not commensurate with other peers their age.

So here is the information I include in such reports (after I’ve gathered pertinent background information in the form of relevant intakes and questionnaires, of course). Naturally, detailed BACKGROUND HISTORY section is a must! Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal development should be prominently featured there. All pertinent medical history needs to get documented as well as all of the child’s developmental milestones in the areas of cognition, emotional development, fine and gross motor function, and of course speech and language. Here, I also include a family history of red flags: international or domestic adoption of the child (if relevant) as well as familial speech and language difficulties, intellectual impairment, psychiatric disorders, special education placements, or documented deficits in the areas of literacy (e.g., reading, writing, and spelling). After all, if any of the above issues are present in isolation or in combination, the risk for language and literacy deficits increases exponentially, and services are strongly merited for the child in question.

For bilingual children, the next section will cover LANGUAGE BACKGROUND AND USE. Here, I describe how many and which languages are spoken in the home and how well does the child understand and speak any or all of these languages (as per parental report based on questionnaires).

After that, I move on to describe the child’s ADAPTIVE BEHAVIOR during the assessment. In this section, I cover emotional relatedness, joint attention, social referencing, attention skills, communicative frequency, communicative intent, communicative functions, as well as any and all unusual behaviors noted during the therapy session (e.g., refusal, tantrums, perseverations, echolalia, etc.) Then I move on to PLAY SKILLS. For the purpose of play assessment, I use the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000). In this section, I describe where the child is presently with respect to play skills, and where they actually need to be developmentally (excerpt below).

“During today’s assessment, LS’s play skills were judged to be significantly reduced for his age. A child of LS’s age (30 months) is expected to engage in a number of isolated pretend play activities with realistic props to represent daily experiences (playing house) as well as less frequently experienced events (e.g., reenacting a doctor’s visit, etc.) (corresponds to Stage VI on the Westby Play Scale, Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000)). Contrastingly, LS presented with limited repertoire routines, which were characterized primarily by exploration of toys, such as operating simple cause and effect toys (given modeling) or taking out and then putting back in playhouse toys. LS’s parents confirmed that the above play schemas were representative of play interactions at home as well. Today’s LS’s play skills were judged to be approximately at Stage II (13 – 17 months) on the Westby Play Scale, (Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000)) which is significantly reduced for a child of LS’s age, since it is almost approximately ±15 months behind his peers. Thus, based on today’s play assessment, LS’s play skills require therapeutic intervention. “

Sections on AUDITORY FUNCTION, PERIPHERAL ORAL MOTOR EXAM, VOCAL PARAMETERS, FLUENCY AND RESONANCE (and if pertinent FEEDING and SWALLOWING follow) (more on that in another post).

Now, it’s finally time to get to the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the report ARTICULATION AND PHONOLOGY as well as RECEPTIVE and EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE (more on PRAGMATIC ASSESSMENT in another post).

First, here’s what I include in the ARTICULATION AND PHONOLOGY section of the report.

- Phonetic inventory: all the sounds the child is currently producing including (short excerpt below):

- Consonants: plosive (/p/, /b/, /m/), alveolar (/t/, /d/), velar (/k/, /g/), glide (/w/), nasal (/n/, /m/) glottal (/h/)

- Vowels and diphthongs: ( /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/, /ou/, /ai/)

- Phonotactic repertoire: What type of words comprised of how many syllables and which consonant-vowel variations the child is producing (excerpt below)

- LS primarily produced one syllable words consisting of CV (e.g., ke, di), CVC (e.g., boom), VCV (e.g., apo) syllable shapes, which is reduced for a child his age.

- Speech intelligibility in known and unknown contexts

- Phonological processes analysis

Now that I have described what the child is capable of speech-wise, I discuss where the child needs to be developmentally:

“A child of LS’s age (30 months) is expected to produce additional consonants in initial word position (k, l, s, h), some consonants (t, d, m, n, s, z) in final word position (Watson & Scukanec, 1997b), several consonant clusters (pw, bw, -nd, -ts) (Stoel-Gammon, 1987) as well as evidence a more sophisticated syllable shape structure (e.g., CVCVC) Furthermore, a 30 month old child is expected to begin monitoring and repairing own utterances, adjusting speech to different listeners, as well as practicing sounds, words, and early sentences (Clark, adapted by Owens, 1996, p. 386) all of which LS is not performing at this time. Based on above developmental norms, LS’s phonological abilities are judged to be significantly below age-expectancy at this time. Therapy is recommended in order to improve LS’s phonological skills.”

At this point, I am ready to move on to the language portion of the assessment. Here it is important to note that a number of assessments for toddlers under 3 years of age contain numerous limitations. Some such as REEL-3 or Rosetti (a criterion-referenced vs. normed-referenced instrument) are observational or limitedly interactive in nature, while others such as PLS-5, have a tendency to over inflate scores, resulting in a significant number of children not qualifying for rightfully deserved speech-language therapy services. This is exactly why it’s so important that SLPs have a firm knowledge of developmental milestones! After all, after they finish describing what the child is capable of, they then need to describe what the developmental expectations are for a child this age (excerpts below).

At this point, I am ready to move on to the language portion of the assessment. Here it is important to note that a number of assessments for toddlers under 3 years of age contain numerous limitations. Some such as REEL-3 or Rosetti (a criterion-referenced vs. normed-referenced instrument) are observational or limitedly interactive in nature, while others such as PLS-5, have a tendency to over inflate scores, resulting in a significant number of children not qualifying for rightfully deserved speech-language therapy services. This is exactly why it’s so important that SLPs have a firm knowledge of developmental milestones! After all, after they finish describing what the child is capable of, they then need to describe what the developmental expectations are for a child this age (excerpts below).

RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE

“LS’s receptive language abilities were judged to be scattered between 11-17 months of age (as per clinical observations as well as informal PLS-5 and REEL-3 findings), which is also consistent with his play skills abilities (see above). During the assessment LS was able to appropriately understand prohibitive verbalizations (e.g., “No”, “Stop”), follow simple 1 part directions (when repeated and combined with gestures), selectively attend to speaker when his name was spoken (behavioral), perform a routine activity upon request (when combined with gestures), retrieve familiar objects from nearby (when provided with gestures), identify several major body parts (with prompting) on a doll only, select a familiar object when named given repeated prompting, point to pictures of familiar objects in books when named by adult, as well as respond to yes/no questions by using head shakes and head nods. This is significantly below age-expectancy.

A typically developing child 30 months of age is expected to spontaneously follow (without gestures, cues or prompts) 2+ step directives, follow select commands that require getting objects out of sight, answer simple “wh” questions (what, where, who), understand select spatial concepts, (in, off, out of, etc), understand select pronouns (e.g., me, my, your), identify action words in pictures, understand concept sizes (‘big’, ‘little’), identify simple objects according to their function, identify select clothing items such as shoes, shirt, pants, hat (on self or caregiver) as well as understand names of farm animals, everyday foods, and toys. Therapeutic intervention is recommended in order to increase LS’s receptive language abilities.

EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE:

“During today’s assessment, LS’s expressive language skills were judged to be scattered between 10-15 months of age (as per clinical observations as well as informal PLS-5 and REEL-3 findings). LS was observed to communicate primarily via proto-imperative gestures (requesting and object via eye gaze, reaching) as well as proto-declarative gestures (showing an object via eye gaze, reaching, and pointing). Additionally, LS communicated via vocalizations, head nods, and head shakes. According to parental report, at this time LS’s speaking vocabulary consists of approximately 15-20 words (see word lists below). During the assessment LS was observed to spontaneously produce a number of these words when looking at a picture book, playing with toys, and participating in action based play activities with Mrs. S and clinician. LS was also observed to produce a number of animal sounds when looking at select picture books and puzzles. For therapy planning purposes, it is important to note that LS was observed to imitate more sounds and words, when they were supported by action based play activities (when words and sounds were accompanied by a movement initiated by clinician and then imitated by LS). Today LS was observed to primarily communicate via a very limited number of imitated and spontaneous one word utterances that labeled basic objects and pictures in his environment, which is significantly reduced for his age.

A typically developing child of LS’s chronological age (30 months) is expected to possess a minimum vocabulary of 200+ words (Rescorla, 1989), produce 2-4 word utterance combinations (e.g., noun + verb, verb + noun + location, verb + noun + adjective, etc), in addition to asking 2-3 word questions as well as maintaining a topic for 2+ conversational turns. Therapeutic intervention is recommended in order to increase LS’s expressive language abilities.”

Here you have a few speech-language evaluation excerpts which describe not just what the child is capable of but where the child needs to be developmentally. Now it’s just a matter of summarizing my IMPRESSIONS (child’s strengths and needs), RECOMMENDATIONS as well as SUGGESTED (long and short term) THERAPY GOALS. Now the parents have some understanding regarding their child’s strengths and needs. From here, they can also track their child’s progress in therapy as they now have some idea to what it can be compared to.

Now I know that many of you will tell me, that this is a ‘perfect world’ evaluation conducted by a private therapist with an unlimited amount of time on her hands. And to some extent, many of you will be right! Yes, such an evaluation was a result of more than 30 minutes spent face-to-face with the child. All in all, it took probably closer to 90 minutes of face to face time to complete it and a few hours to write. And yes, this is a luxury only a few possess and many therapists in the early intervention system lack. But in the long run, such evaluations pay dividends not only, obviously, to your clients but to SLPs who perform them. They enhance and grow your reputation as an evaluating therapist. They even make sense from a business perspective. If you are well-known and highly sought after due to your evaluating expertise, you can expect to be compensated for your time, accordingly. This means that if you decide that your time and expertise are worth private pay only (due to poor insurance reimbursement or low EI rates), you can be sure that parents will learn to appreciate your thoroughness and will choose you over other providers.

Now I know that many of you will tell me, that this is a ‘perfect world’ evaluation conducted by a private therapist with an unlimited amount of time on her hands. And to some extent, many of you will be right! Yes, such an evaluation was a result of more than 30 minutes spent face-to-face with the child. All in all, it took probably closer to 90 minutes of face to face time to complete it and a few hours to write. And yes, this is a luxury only a few possess and many therapists in the early intervention system lack. But in the long run, such evaluations pay dividends not only, obviously, to your clients but to SLPs who perform them. They enhance and grow your reputation as an evaluating therapist. They even make sense from a business perspective. If you are well-known and highly sought after due to your evaluating expertise, you can expect to be compensated for your time, accordingly. This means that if you decide that your time and expertise are worth private pay only (due to poor insurance reimbursement or low EI rates), you can be sure that parents will learn to appreciate your thoroughness and will choose you over other providers.

So, how about it? Can you give it a try? Trust me, it’s worth it!

Selected References:

- Owens, R. E. (1996). Language development: An introduction (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Rescorla, L. (1989). The Language Development Survey: A screening tool for delayed language in toddlers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 587–599.

- Selby, J. C., Robb, M. P., & Gilbert, H. R. (2000). Normal vowel articulations between 15 and 36 months of age. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 14, 255-266.

- Stoel-Gammon, C. (1987). Phonological skills of 2-year-olds. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 18, 323-329.

- Watson, M. M., & Scukanec, G. P. (1997b). Profiling the phonological abilities of 2-year-olds: A longitudinal investigation. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 13, 3-14.

For more information on EI Assessments click on any of the below posts:

- Part II: Early Intervention Evaluations PART II: Assessing Suspected Motor Speech Disorders in Children Under 3

- Part III: Early Intervention Evaluations PART III: Assessing Children Under 2 Years of Age

- Part IV: Early Intervention Evaluations PART IV:Assessing Social Pragmatic Abilities of Children Under 3

Is it a Difference or a Disorder? Free Resources for SLPs Working with Bilingual and Multicultural Children

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

However, today the aim of today’s post is not on the above product but rather on the FREE free bilingual and multicultural resources available to SLPs online in their quest of differentiating between a language difference from a language disorder in bilingual and multicultural children.

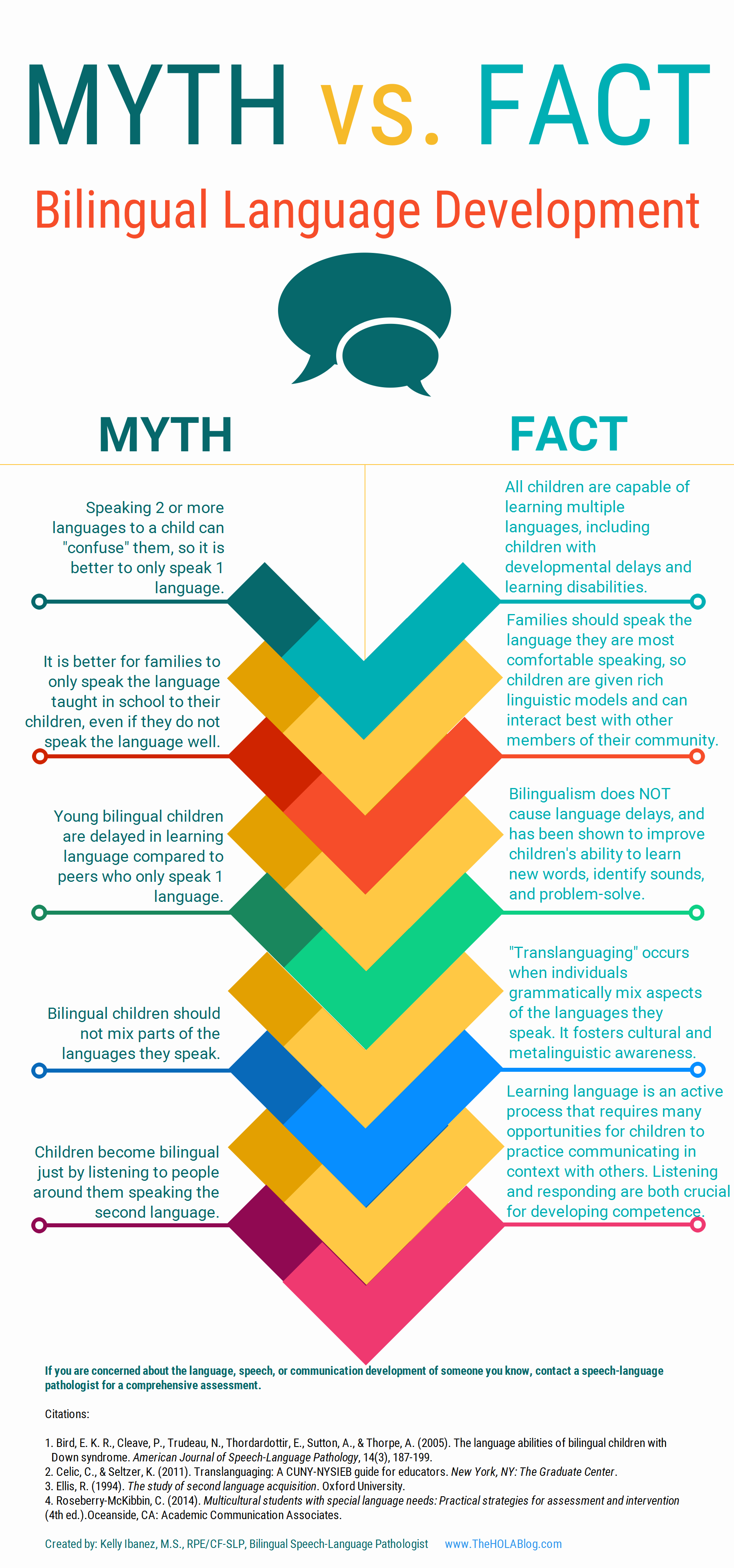

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let us now move on to the typical phonological development of English speaking children. After all, in order to compare other languages to English, SLPs need to be well versed in the acquisition of speech sounds in the English language. Children’s speech acquisition, developed by Sharynne McLeod, Ph.D., of Charles Sturt University, is one such resource. It contains a compilation of data on typical speech development for English speaking children, which is organized according to children’s ages to reflect a typical developmental sequence.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

![]() Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

The Leader’s Project Website is another highly informative source of FREE information on bilingual assessments, intervention, and FREE CEUS.

Now, I’d like to list some resources regarding language transfer errors.

This chart from Cengage Learning contains a nice, concise Language Guide to Transfer Errors. While it is aimed at multilingual/ESL writers, the information contained on the site is highly applicable to multilingual speakers as well.

You can also find a bonus transfer chart HERE. It contains information on specific structures such as articles, nouns, verbs, pronouns, adverbs, adjectives, word order, questions, commands, and negatives on pages 1-6 and phonemes on pages 7-8.

A final bonus chart entitled: Teacher’s Resource Guide of Language Transfer Issues for English Language Learners containing information on grammar and phonics for 10 different languages can be found HERE.

Similarly, this 16-page handout: Language Transfers: The Interaction Between English and Students’ Primary Languages also contains information on phonics and grammar transfers for Spanish, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Hmong Korean, and Khmer languages.

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

- Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment

- Strategies in the acquisition of segments and syllables in Russian-speaking children

- Language Development of Bilingual Russian/ English Speaking Children Living in the United States: A Review of the Literature

- The acquisition of syllable structure by Russian-speaking children with SLI

To determine information about the children’s language development and language environment, in both their first and second language, visit the CHESL Centre website for The Alberta Language Development Questionnaire and The Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire

There you have it! FREE bilingual/multicultural SLP resources compiled for you conveniently in one place. And since there are much more FREE GEMS online, I’d love it if you guys contributed to and expanded this modest list by posting links and title descriptions in the comments section below for others to benefit from!

Together we can deliver the most up to date evidence-based assessment and intervention to bilingual and multicultural students that we serve! Click HERE to check out the FREE Resources in the SLPs for Evidence-Based Practice Group

Helpful Bilingual Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions

- Dynamic Assessment of Bilingual and Multicultural Learners in Speech-Language Pathology

- Practical Strategies for Monolingual SLPs Assessing and Treating Bilingual Children

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian-speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

- Creating Translanguaging Classrooms and Therapy Rooms

APD Update: New Developments on an Old Controversy

In the past two years, I wrote a series of research-based posts (HERE and HERE) regarding the validity of (Central) Auditory Processing Disorder (C/APD) as a standalone diagnosis as well as questioned the utility of it for classification purposes in the school setting.

In the past two years, I wrote a series of research-based posts (HERE and HERE) regarding the validity of (Central) Auditory Processing Disorder (C/APD) as a standalone diagnosis as well as questioned the utility of it for classification purposes in the school setting.

Once again I want to reiterate that I was in no way disputing the legitimate symptoms (e.g., difficulty processing language, difficulty organizing narratives, difficulty decoding text, etc.), which the students diagnosed with “CAPD” were presenting with.

Rather, I was citing research to indicate that these symptoms were indicative of broader linguistic-based deficits, which required targeted linguistic/literacy-based interventions rather than recommendations for specific prescriptive programs (e.g., CAPDOTS, Fast ForWord, etc.), or mere accommodations.

I was also significantly concerned that overfocus on the diagnosis of (C)APD tended to obscure REAL, language-based deficits in children and forced SLPs to address erroneous therapeutic targets based on AuD recommendations or restricted them to a receipt of mere accommodations rather than rightful therapeutic remediation. Continue reading APD Update: New Developments on an Old Controversy

Review and Giveaway of Strategies by Numbers (by SPELL-Links)

Today I am reviewing a fairly recently released (2014) book from the Learning By Design, Inc. team entitled SPELL-Links Strategies by Numbers. This 57 page instructional guide was created to support the implementation of the SPELL-Links to Reading and Writing Word Study Curriculum as well as to help students “use the SPELL-Links strategies anytime in any setting.’ (p. iii) Its purpose is to enable students to strategize their way to writing and reading rather than overrelying on memorization techniques.

SPELL-Links Strategies by Numbers contains in-depth explanations of SPELL-Links’ 14 strategies for spelling and reading, detailed instructions on how to teach the strategies during writing and reading activities, as well as helpful ideas for supporting students as they further acquire literacy skills. It can be used by a wide array of professionals including classroom teachers, speech-language pathologists, reading improvement teachers, learning disabilities teachers, aides, tutors, as well as parents for teaching word study lessons or as carryover and practice during reading and writing tasks.

The author includes a list of key terms used in the book as well as a guide with instructional icons

The goal of the 14 strategies listed in the book is to build vocabulary, improve spelling, word decoding, reading fluency, and reading comprehension as well as improve students’ writing skills. While each strategy is presented in isolation under its own section, the end result is for students to fully integrate and apply multiple strategies when reading or writing.

Here’s the list of the 14 strategies in order of appearance as applied to spelling and reading:

- Sound It Out

- Check the Order

- Catch the Beat

- Listen Up

- A Little Stress Will Help This Mess

- No Fouls

- Play By the Rules

- Use Rhyme This Time

- Spell What You Mean and Mean What You Spell

- Be Smart About Word Parts

- Build on the Base

- Invite the Relatives

- Fix the Funny Stuff

- Look It Up

Each strategy includes highly detailed implementation instructions with students including pictorial support as well as both instructor and student guidance for practice at various levels during writing and reading tasks. At the end of the book all the strategies are succinctly summarized in handy table, which is also provided to the user separately as a double sided one page insert printed on reinforced paper to be used as a guide when the book is not handy.

There are a number of things I like about the book. Firstly, of course it is based on the latest research in reading, writing, and spelling. Secondly, clinicians can use it the absence of SPELL-Links to Reading and Writing Word Study Curriculum since the author’s purpose was to have the students “use the SPELL-Links strategies anytime in any setting.’ (p. iii). Thirdly, I love the fact that the book is based on the connectionist research model, which views spelling and reading as a “dynamic interplay of phonological, orthographic, and semantic knowledge.” (iii). Consequently, the listed strategies focus on simultaneously developing and strengthening phonological, orthographic, semantic and morphological knowledge during reading and writing tasks.

You can find this book for purchase on the Learning By Design, Inc. Store HERE. Finally, due to the generosity of Jan Wasowicz PhD the book’s author, you can enter my Rafflecopter giveaway below for a chance to win your own copy!