In 2020 I reviewed a product kit (instructional guide and cards) from SPELL-Links™ Learning By Design, Inc. entitled Wordtivities: Word Study Instruction for Spelling, Vocabulary, and Reading. Today, I am reviewing a companion to that product kit: SPELL-Links™ Wordtivities Word Lists. This 180-page guide contains sets of pattern-focused word lists for whole class, small group, and 1:1 word study instruction purposes. Each grade-level word list supports the simultaneous development of pattern-specific phonological (sound), orthographic (letter), and semantic morphological (meaning) skills. The aim of this guide is to systematically address spelling, reading, speaking, and listening all together by developing a neural network for literacy and language.

SPELL-Links™ Wordtivities Word Lists are useful for students 5+ years of age who have or are in the process of developing the following knowledge and skills:

- Letter-name knowledge

- Alphabetic letter writing ability

- Mastery of early phonological awareness (PA) skills by being able to segment words into syllables, understand and create rhyming words, and isolate sounds in words

- Basic concept knowledge of directionality (left/right; top/down)

The book is organized by patterns and grade levels (K-6 grade) and by the instructional focus. For each pattern, word lists are organized to support a specific instructional focus: phonological code, orthographic code, morphological code, storage and retrieval of orthographic representations, and writing application.

The Word Lists feature 128 patterns across grades K through 6. The number of patterns taught at each grade level ranges from 9 (K) to 25 (grades 4 and 5).

Here’s an example of a 4th-grade instructional overview:

Overview of Weekly Instruction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88

Pattern: Prefixes pre- (before); mid- (middle); post- (after) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91

Pattern: Prefixes over- (above, more than); super- (superior, exceeding); under- (below, less than);

sub- (under, subordinate) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92

Pattern: ‘l, r’ Clusters ‘lb, ld, lf, lk, lm, lp, lt, lth, lve, lse’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Pattern: ‘l, r’ Clusters ‘rd, rf, rm, rn, rp, rt, rsh, rch, rth, rve, rge’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94

Pattern: ‘l, r’ Clusters ‘rse, rce’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Pattern: Homophones Set 1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

Pattern: Suffixes -ion, -ation, -ition (N) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Pattern: Suffix -ment (N) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98

Pattern: Suffix -en (V, ADJ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 99

Pattern: ‘m, n, ng’ Clusters ‘nd, nt, mp, mph, nth, nch, ngth, nge’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Pattern: ‘m, n, ng’ Clusters ‘nk, nc’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Pattern: ‘m, n, ng’ clusters ‘nce, nse’ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

Pattern: Homophones Set 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

Pattern: Syllabic-r Vowel Sound as in bird, father . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

Pattern: Suffix -ward (ADJ, ADV) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

Pattern: Unstressed Vowels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106

Pattern: Syllabic-l Vowel Sound as in bottle, pencil . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

Pattern: Suffix -al (ADJ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 108

Pattern: Suffixes -able, ible (ADJ) …………………………………………….. 109

Pattern: Suffix -ous (ADJ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110

Pattern: Suffixes -ive, -ative, -itive (N, ADJ)………………………………………. 111

Pattern: Suffix -ure (N) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 112

Pattern: Contractions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 113

Pattern: Prefix tele- (far); micro- (tiny) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

Pattern: Prefixes mono-, uni-, bi-, tri-, quad-, oct- (number affixes) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115

Pattern Review

The weekly instruction will look as follows:

- Monday-Tuesday: Review of Phonological and Orthographic Codes (these word pattern lists are organized into 3 groups to support differentiated instruction)

- Wednesday–Thursday: Morphology

- Friday: Mental Orthographic Representations and Application to Sentence Writing

The book comes with access to digital Materials Library, which contains access to the following materials:

- List of pattern-loaded stories

- SPELL-Links™ Pattern Inventory & Analysis Tool (PIAT)

The appeal of the product for me is that it offers numerous group-based opportunities for the solidification of evidence-based instructional practices. The book comes with very detailed implementation instructions. A variety of daily activities allow students to further advance their abilities in the areas of prefixes and suffixes, numerous homophones and clusters, unstressed vowels and even contractions. The kit also offers several appendices that review the spelling rules for word roots prefixes and suffixes, as well as detailed recommendations for pattern-loaded reading materials. To me, the appeal of this curriculum is rather multifaceted. It continues to be very difficult to find an evidence-based group instruction curriculum, and Wordtivities Word Lists once again fit the bill for it. Because it focuses on skills integration of spelling, reading, speaking, and listening it allows the students to engage in contextually based opportunities to become better listeners, speakers, readers, spellers and writers.

You can find this kit for purchase on the SPELL-Links™ Learning By Design, Inc. Store HERE.

And now for the fun part. Want to win your own copy of SPELL-Links™ Wordtivities Word Lists? Enter to win here: I want to win SPELL-Links Wordtivities Word Lists! | Learning By Design They’ll send one lucky person a copy of SPELL-Links™ Wordtivities Word Lists. Entries are accepted until 3/1/24 at 5 pm CST. The winner will be notified by email.

Today I am reviewing a newly released (2019) kit (instructional guide and cards) from the Learning By Design, Inc. entitled Wordtivities:

Today I am reviewing a newly released (2019) kit (instructional guide and cards) from the Learning By Design, Inc. entitled Wordtivities:

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

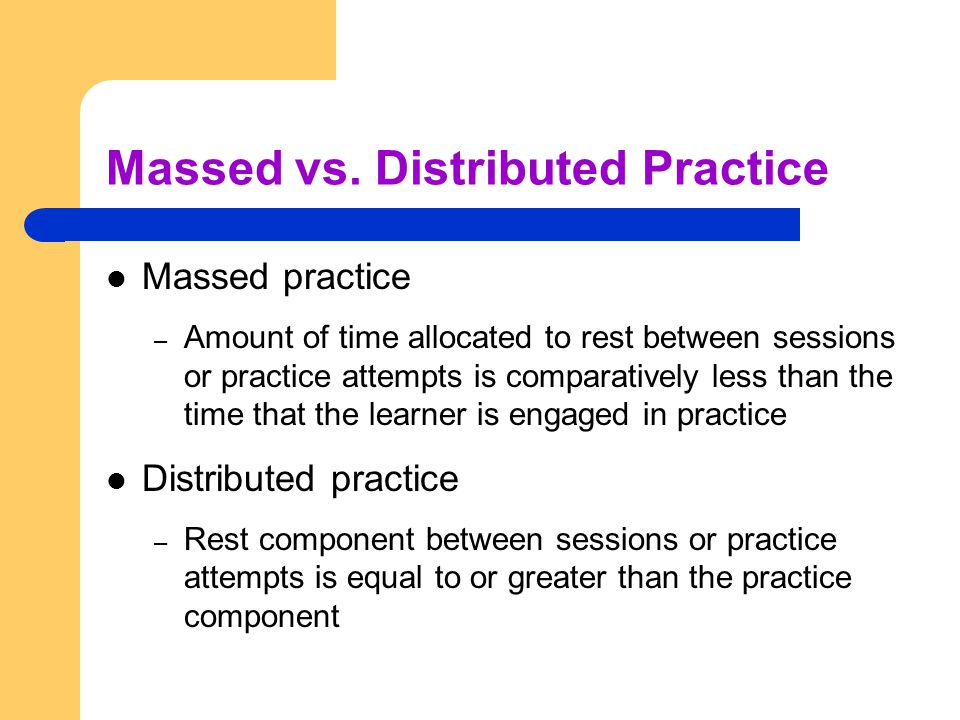

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute. After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than

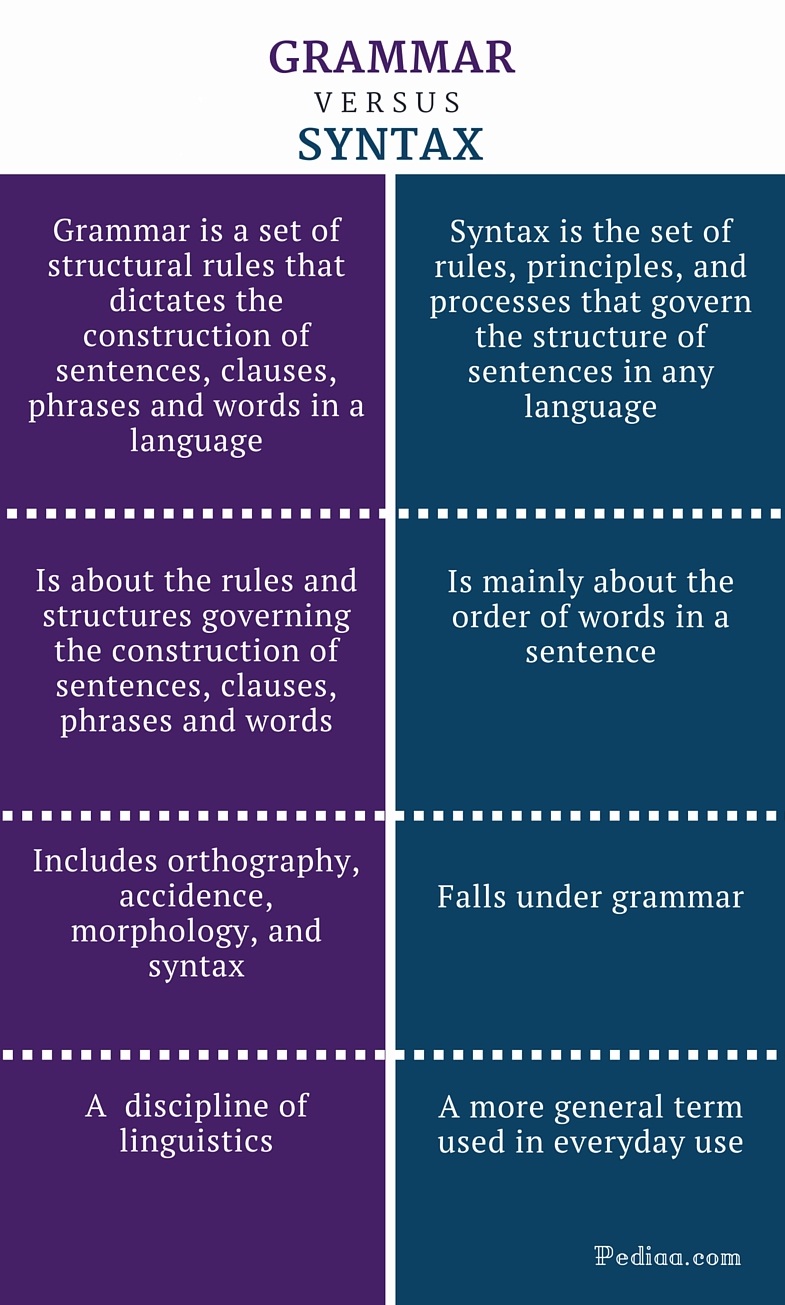

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by  Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements). There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same  Summer is in full swing and for many SLPs that means a welcome break from work. However, for me, it’s business as usual, since my program is year around, and we have just started our extended school year program.

Summer is in full swing and for many SLPs that means a welcome break from work. However, for me, it’s business as usual, since my program is year around, and we have just started our extended school year program.

After the completion of the screening, the app generates a two-page report which describes the students’ abilities as:

After the completion of the screening, the app generates a two-page report which describes the students’ abilities as: The Profile of Phonological Awareness (Pro-PA), an informal phonological awareness screening was administered to “Justine” in May 2017 to further determine the extent of her phonological awareness strengths and weaknesses.

The Profile of Phonological Awareness (Pro-PA), an informal phonological awareness screening was administered to “Justine” in May 2017 to further determine the extent of her phonological awareness strengths and weaknesses. In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

High comorbidity between language and psychiatric disorders has been well documented (Beitchman, Cohen, Konstantaras, & Tannock, 1996; Cohen, Barwick, Horodezky, Vallence, & Im, 1998; Toppelberg & Shapiro, 2000). However, a lesser known fact is that there’s also a significant under-diagnosis of language impairments in children with psychiatric disorders.

High comorbidity between language and psychiatric disorders has been well documented (Beitchman, Cohen, Konstantaras, & Tannock, 1996; Cohen, Barwick, Horodezky, Vallence, & Im, 1998; Toppelberg & Shapiro, 2000). However, a lesser known fact is that there’s also a significant under-diagnosis of language impairments in children with psychiatric disorders.