Several years ago I wrote a post about how to perform clinical reading assessments of adolescent students. Today I am writing a follow-up post with a focus on the clinical reading assessment of elementary-aged students. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 2-7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling elementary-aged readers. Continue reading Clinical Assessment of Reading Abilities of Elementary Aged Children

Category: Speech-Language Report Tutorials

New Additions to My Comprehensive Report Tutorials and Templates

I have previously written regarding my line of products on the topic of: “Comprehensive Report Tutorials“. I had already added a number of editable comprehensive report templates to my online store.

These templates summarize popular speech-language pathology tests with meticulous detail. Each editable template will contain:

- Formal testing results breakdown in the form of a table

- A detailed overview of each subtest including a variety of hypotheses behind the student errors

- Summary of the students perceived deficits on the test and their correlation with language/literacy based deficits

- Long-term goals and detailed short-term’s objectives

Below is a select list of templates which are already available:

- Test of Integrated Language and Literacy Skills

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5: Metalinguistics

- Listening Comprehension Tests (Elementary and adolescent versions)

- WORD Tests (Elementary and adolescent versions)

- Tests of Problem Solving (Elementary and Adolescent versions)

- Social Language Development Tests (Elementary and Adolescent versions)

- Executive Functions Test- Elementary

- Tests of Reading Comprehension

- Tests of Written Expression

- Comprehensive Tests of Phonological Processing

Available templates to date:

- TILLS Report Template

- SLDTE Report Template

- SLDTA Report Template

- CELF-5M Report Template

- TOPS-3 Report Template

- TOPS-2 Report Template

Continue reading New Additions to My Comprehensive Report Tutorials and Templates

On the Limitations of Using Vocabulary Tests with School-Aged Students

Those of you who read my blog on a semi-regular basis, know that I spend a considerable amount of time in both of my work settings (an outpatient school located in a psychiatric hospital as well as private practice), conducting language and literacy evaluations of preschool and school-aged children 3-18 years of age. During that process, I spend a significant amount of time reviewing outside speech and language evaluations. Interestingly, what I have been seeing is that no matter what the child’s age is (7 or 17), invariably some form of receptive and/or expressive vocabulary testing is always mentioned in their language report. Continue reading On the Limitations of Using Vocabulary Tests with School-Aged Students

Analyzing Narratives of School-Aged Children

As mentioned previously, for elicitation purposes, I frequently use the books recommended by the SALT Software website, which include: ‘Frog Where Are You?’ by Mercer Mayer, ‘Pookins Gets Her Way‘ and ‘A Porcupine Named Fluffy‘ by Helen Lester, as well as ‘Dr. DeSoto‘ by William Steig. Continue reading Analyzing Narratives of School-Aged Children

New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

September is quickly approaching and school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) are preparing to go back to work. Many of them are looking to update their arsenal of speech and language materials for the upcoming academic school year.

With that in mind, I wanted to update my readers regarding all the new products I have recently created with a focus on assessment and treatment in speech language pathology. Continue reading New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

Adolescent Assessments in Action: Clinical Reading Evaluation

In the past several years, due to an influx of adolescent students with language and learning difficulties on my caseload, I have begun to research in depth aspects of adolescent language development, assessment, and intervention.

In the past several years, due to an influx of adolescent students with language and learning difficulties on my caseload, I have begun to research in depth aspects of adolescent language development, assessment, and intervention.

While a number of standardized assessments are available to test various components of adolescent language from syntax and semantics to problem-solving and social communication, etc., in my experience with this age group, frequently, clinical assessments (vs. the standardized tests), do a far better job of teasing out language difficulties in adolescents.

Today I wanted to write about the importance of performing a clinical reading assessment as part of select* adolescent language and literacy evaluations.

There are a number of standardized tests on the market, which presently assess reading. However, not all of them by far are as functional as many clinicians would like them to be. To illustrate, one popular reading assessment is the Gray Oral Reading Tests-5 (GORT-5). It assesses the student’s rate, accuracy, fluency, and comprehension abilities. While it’s a useful test to possess in one’s assessment toolbox, it is not without its limitations. In my experience assessing adolescent students with literacy deficits, many can pass this test with average scores, yet still present with pervasive reading comprehension difficulties in the school setting. As such, as part of the assessment process, I like to administer clinical reading assessments to students who pass the standardized reading tests (e.g., GORT-5), in order to ensure that the student does not possess any reading deficits at the grade text level.

So how do I clinically assess the reading abilities of struggling adolescent learners?

First, I select a one-page long grade level/below grade-level text (for very impaired readers). I ask the student to read the text, and I time the first minute of their reading in order to analyze their oral reading fluency or words correctly read per minute (wcpm).

For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 5 – 7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling adolescent readers. In some cases using a below grade level text allows me to starkly illustrate the extent of the student’s reading difficulties. Below is an example of one of such a clinical reading assessments in action.

For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Content Reading for Geography, Social Studies, & Science. Texts for grades 5 – 7 of the series are perfect for assessment of struggling adolescent readers. In some cases using a below grade level text allows me to starkly illustrate the extent of the student’s reading difficulties. Below is an example of one of such a clinical reading assessments in action.

CLINICAL READING ASSESSMENT: 8th Grade Male

A clinical reading assessment was administered to TS, a 15-5-year-old male, on a supplementary basis in order to further analyze his reading abilities. Given the fact that TS was reported to present with grade-level reading difficulties, the examiner provided TS a 7th-grade text by Continental Press. TS was asked to read aloud the 7 paragraph long text, and then answer factual and inferential questions, summarize the presented information, define select context embedded vocabulary words as well as draw conclusions based on the presented text. (Please note that in order to protect the client’s privacy some portions of the below assessment questions and responses were changed to be deliberately vague).

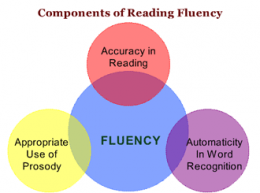

Reading Fluency: TS’s reading fluency (automaticity, prosody, accuracy and speed, expression, intonation, and phrasing) during the reading task was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody.

Reading Fluency: TS’s reading fluency (automaticity, prosody, accuracy and speed, expression, intonation, and phrasing) during the reading task was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody.

With respect to specific errors, TS was observed to occasionally add word fillers to text (e.g., and, a, etc.), change morphological endings of select words (e.g., read /elasticity/ as /elastic/, etc.) as well as substitute similar looking words (e.g., from/for; those/these, etc.) during reading. He occasionally placed stress on the first vs. second syllable in disyllabic words, which resulted in distorted word productions (e.g., products, residual, upward, etc.), as well as inserted extra words into text (e.g., read: “until pressure inside the earth starts to build again” as “until pressure inside the earth starts to build up again”). He also began reading a number of his sentences with false starts (e.g., started reading the word “drinking” as ‘drunk’, etc.) and as a result was observed to make a number of self-corrections during reading.

During reading, TS demonstrated adequate tracking movements for text scanning as well as use of context to aid his decoding. For example, TS was observed to read the phonetic spelling of select unfamiliar words in parenthesis (e.g., equilibrium) and then read them correctly in subsequent sentences. However, he exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies and did not always self-correct misread words; dispute the fact that they did not always make sense in the context of the read sentences.

TS’s oral reading rate during today’s reading was judged to be reduced for his age/grade levels. An average 8th grader is expected to have an oral reading rate between 145 and 160 words per minute. In contrast, TS was only able to read 114 words per minute. However, it is important to note that recent research on reading fluency has indicated that as early as by 4th grade reading faster than 90 wcpm will not generate increases in comprehension for struggling readers. Consequently, TS’s current reading rate of off 114 words per minute was judged to be adequate for reading purposes. Furthermore, given the fact that TS’s reading comprehension is already compromised at this rate (see below for further details) rather than making a recommendation to increase his reading rate further, it is instead recommended that intervention focuses on slowing TS’s rate via relevant strategies as well as improving his reading comprehension abilities. Strategies should focus on increasing his opportunities to learn domain knowledge via use of informational texts; purposeful selection of texts to promote knowledge acquisition and gain of expertise in different domains; teaching morphemic as well as semantic feature analyses (to expand upon already robust vocabulary), increasing discourse and critical thinking with respect to informational text, as well as use of graphic organizers to teach text structure and conceptual frameworks.

Verbal Text Summary: TS’s text summary following his reading was very abbreviated, simplified, and confusing. When asked: “What was this text about?” Rather than stating the main idea, TS nonspecifically provided several vague details and was unable to elaborate further. When asked: “Do you think you can summarize this story for me from beginning to the end?” TS produced the two disjointed statements, which did not adequately address the presented question When asked: “What is the main idea of this text.” TS vaguely responded: “Science,” which was the broad topic rather than the main idea of the story.

Text Vocabulary Comprehension:

Text Vocabulary Comprehension:

After that, TS was asked a number of questions regarding story vocabulary. The first word presented to him was “equilibrium”. When asked: “What does ‘equilibrium’ mean?” TS first incorrectly responded: “temperature”. Then when prompted: “Anything else?” TS correctly replied: “balance.” He was then asked to provide some examples of how nature leans towards equilibrium from the story. TS nonspecifically produced: “Ah, gravity.” When asked to explain how gravity contributes to the process of equilibrium TS again nonspecifically replied: “gravity is part of the planet”, and could not elaborate further. TS was then asked to define another word from the text provided to him in a sentence: “Scientists believe that this is residual heat remaining from the beginnings of the solar system.” What is the meaning of the word: “residual?” TS correctly identified: “remaining.” Then the examiner asked him to define the term found in the last paragraph of the text: “What is thermal equilibrium?” TS nonspecifically responded: “a balance of temperature”, and was unable to elaborate further.

Reading Comprehension (with/out text access):

TS was also asked to respond to a number of factual text questions without the benefit of visual support. However, he presented with significant difficulty recalling text details. TS was asked: When asked, “Why did this story mention ____? What did they have to do with ____?” TS responded nonspecifically, “______.” When prompted to tell more, TS produced a rambling response which did not adequately address the presented question. When asked: “Why did the text talk about bungee jumpers? How are they connected to it?” TS stated, “I am ah, not sure really.”

Finally, TS was provided with a brief worksheet which accompanied the text and asked to complete it given the benefit of written support. While TS’s performance on this task was better, he still achieved only 66% accuracy and was only able to answer 4 out of 6 questions correctly. On this task, TS presented with difficulty identifying the main idea of the third paragraph, even after being provided with multiple choice answers. He also presented with difficulty correctly responding to the question pertaining to the meaning of the last paragraph.

Impressions: Clinical below grade-level reading comprehension assessment reading revealed that TS presents with a number of reading related difficulties. TS’s reading fluency was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody. TS’s understanding as well as his verbal summary of the presented text was immature for his age and was characterized by impaired gestalt processing of information resulting in an ineffective and confusing summarization. While TS’s text-based vocabulary knowledge was deemed to be grossly adequate for his age, his reading comprehension abilities were judged to be impaired for his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve TS’s reading abilities. (See Impressions and Recommendations sections for further details).

Impressions: Clinical below grade-level reading comprehension assessment reading revealed that TS presents with a number of reading related difficulties. TS’s reading fluency was marked by monotone vocal quality, awkward word stress, imprecise articulatory contacts, false-starts, self–revisions, awkward mid-sentential pauses, limited pausing for punctuation, as well as misreadings and word substitutions, all of which resulted in an impaired reading prosody. TS’s understanding as well as his verbal summary of the presented text was immature for his age and was characterized by impaired gestalt processing of information resulting in an ineffective and confusing summarization. While TS’s text-based vocabulary knowledge was deemed to be grossly adequate for his age, his reading comprehension abilities were judged to be impaired for his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve TS’s reading abilities. (See Impressions and Recommendations sections for further details).

There you have it! This is just one of many different types of informal reading assessments, which I occasionally conduct with adolescents who attain average scores on reading fluency and reading comprehension tests such as the GORT-5 or the Test of Reading Comprehension -4 (TORC-4), but still present with pervasive reading difficulties working with grade level text.

You can find more information on the topic of adolescent assessments (including other comprehensive informal write-up examples) in this recently developed product entitled: Assessment of Adolescents with Language and Literacy Impairments in Speech Language Pathology currently available in my online store.

What about you? What type of informal tasks and materials are you using to assess your adolescent students’ reading abilities and why do you like using them?

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Adolescent Assessment Resources:

- Assessment of Adolescents with Language and Literacy Impairments in Speech Language Pathology

- Comprehensive Literacy Checklist For School-Aged Children

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents

The Importance of Narrative Assessments in Speech Language Pathology (Revised)

As SLPs we routinely administer a variety of testing batteries in order to assess our students’ speech-language abilities. Grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and sentence formulation get frequent and thorough attention. But how about narrative production? Does it get its fair share of attention when the clinicians are looking to determine the extent of the child’s language deficits? I was so curious about what the clinicians across the country were doing that in 2013, I created a survey and posted a link to it in several SLP-related FB groups. I wanted to find out how many SLPs were performing narrative assessments, in which settings, and with which populations. From those who were performing these assessments, I wanted to know what type of assessments were they using and how they were recording and documenting their findings. Since the purpose of this survey was non-research based (I wasn’t planning on submitting a research manuscript with my findings), I only analyzed the first 100 responses (the rest were very similar in nature) which came my way, in order to get the general flavor of current trends among clinicians, when it came to narrative assessments. Here’s a brief overview of my [limited] findings. Continue reading The Importance of Narrative Assessments in Speech Language Pathology (Revised)

As SLPs we routinely administer a variety of testing batteries in order to assess our students’ speech-language abilities. Grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and sentence formulation get frequent and thorough attention. But how about narrative production? Does it get its fair share of attention when the clinicians are looking to determine the extent of the child’s language deficits? I was so curious about what the clinicians across the country were doing that in 2013, I created a survey and posted a link to it in several SLP-related FB groups. I wanted to find out how many SLPs were performing narrative assessments, in which settings, and with which populations. From those who were performing these assessments, I wanted to know what type of assessments were they using and how they were recording and documenting their findings. Since the purpose of this survey was non-research based (I wasn’t planning on submitting a research manuscript with my findings), I only analyzed the first 100 responses (the rest were very similar in nature) which came my way, in order to get the general flavor of current trends among clinicians, when it came to narrative assessments. Here’s a brief overview of my [limited] findings. Continue reading The Importance of Narrative Assessments in Speech Language Pathology (Revised)

Early Intervention Evaluations PART IV:Assessing Social Pragmatic Abilities of Children Under 3

To date, I have written 3 posts on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first post offered suggestions on what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders and my third post described what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age.

To date, I have written 3 posts on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first post offered suggestions on what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders and my third post described what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age.

Today, I’d like to offer some suggestions on the assessment of social emotional functioning and pragmatics of children, ages 3 and under.

For starters, below is the information I found compiled by a number of researchers on select social pragmatic milestones for the 0-3 age group:

- Peters, Kimberly (2013) Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function

- Hutchins & Prelock, (2016) Select Social Cognitive Milestones from the Theory of Mind Atlas

3. Development of Theory of Mind (Westby, 2014)

In my social pragmatic assessments of the 0-3 population, in addition, to the child’s adaptive behavior during the assessment, I also describe the child’s joint attention, social emotional reciprocity, as well as social referencing abilities.

Joint attention is the shared focus of two individuals on an object. Responding to joint attention refers to the child’s ability to follow the direction of the gaze and gestures of others in order to share a common point of reference. Initiating joint attention involves child’s use of gestures and eye contact to direct others’ attention to objects, to events, and to themselves. The function of initiating joint attention is to show or spontaneously seek to share interests or pleasurable experience with others. (Mundy, et al, 2007)

Social emotional reciprocity involves being aware of the emotional and interpersonal cues of others, appropriately interpreting those cues, responding appropriately to what is interpreted as well as being motivated to engage in social interactions with others (LaRocque and Leach,2009).

Social referencing refers to a child’s ability to look at a caregiver’s cues such as facial expressions, body language and tone of voice in an ambiguous situation in order to obtain clarifying information. (Walden & Ogan, 1988)

Here’s a brief excerpt from an evaluation of a child ~18 months of age:

“RA’s joint attention skills, social emotional reciprocity as well as social referencing were judged to be appropriate for his age. For example, when Ms. N let in the family dog from the deck into the assessment room, RA immediately noted that the dog wanted to exit the room and go into the hallway. However, the door leading to the hallway was closed. RA came up to the closed door and attempted to reach the doorknob. When RA realized that he cannot reach to the doorknob to let the dog out, he excitedly vocalized to get Ms. N’s attention, and then indicated to her in gestures that the dog wanted to leave the room.”

If I happen to know that a child is highly verbal, I may actually include a narrative assessment, when evaluating toddlers in the 2-3 age group. Now, of course, true narratives do not develop in children until they are bit older. However, it is possible to limitedly assess the narrative abilities of verbal children in this age group. According to Hedberg & Westby (1993) typically developing 2-year-old children are at the Heaps Stage of narrative development characterized by

If I happen to know that a child is highly verbal, I may actually include a narrative assessment, when evaluating toddlers in the 2-3 age group. Now, of course, true narratives do not develop in children until they are bit older. However, it is possible to limitedly assess the narrative abilities of verbal children in this age group. According to Hedberg & Westby (1993) typically developing 2-year-old children are at the Heaps Stage of narrative development characterized by

- Storytelling in the form of a collection of unrelated ideas which consist of labeling and describing events

- Frequent switch of topic is evident with lack of central theme and cohesive devices

- The sentences are usually simple declarations which contain repetitive syntax and use of present or present progressive tenses

- In this stage, children possess limited understanding that the character on the next page is still same as on the previous page

In contrast, though typically developing children between 2-3 years of age in the Sequences Stage of narrative development still arbitrarily link story elements together without transitions, they can:

- Label and describe events about a central theme with stories that may contain a central character, topic, or setting

To illustrate, below is a narrative sample from a typically developing 2-year-old child based on the Mercer Mayer’s classic wordless picture book: “Frog Where Are You?”

To illustrate, below is a narrative sample from a typically developing 2-year-old child based on the Mercer Mayer’s classic wordless picture book: “Frog Where Are You?”

- He put a froggy in there

- He’s sleeping

- Froggy came out

- Where did did froggy go?

- Now the dog fell out

- Then he got him

- You are a silly dog

- And then

- where did froggy go?

- In in there

- Up up into the tree

- Up there an owl

- Froggy

- A reindeer caught him

- Then he dropped him

- Then he went into snow

- And then he cleaned up that

- Then stopped right there and see what wha wha wha what he found

- He found two froggies

- They lived happily ever after

Of course, a play assessment for this age group is a must. Since, in my first post, I offered a play skills excerpt from one of my early intervention assessments and in my third blog post, I included a link to the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), I will now move on to the description of a few formal instruments I find very useful for this age group.

Of course, a play assessment for this age group is a must. Since, in my first post, I offered a play skills excerpt from one of my early intervention assessments and in my third blog post, I included a link to the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), I will now move on to the description of a few formal instruments I find very useful for this age group.

While some criterion-referenced instruments such as the Rossetti, contain sections on Interaction-Attachment and Pragmatics, there are other assessments which I prefer for evaluating social cognition and pragmatic abilities of toddlers.

For toddlers 18+months of age, I like using the Language Use Inventory (LUI) (O’Neill, 2009) which is administered in the form of a parental questionnaire that can be completed in approximately 20 minutes. Aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development it contains 180 questions and divided into 3 parts and 14 subscales including:

For toddlers 18+months of age, I like using the Language Use Inventory (LUI) (O’Neill, 2009) which is administered in the form of a parental questionnaire that can be completed in approximately 20 minutes. Aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development it contains 180 questions and divided into 3 parts and 14 subscales including:

- Communication w/t gestures

- Communication w/t words

- Longer sentences

Therapists can utilize the Automated Score Calculator, which accompanies the LUI in order to generate several pages write up or summarize the main points of the LUI’s findings in their evaluation reports.

Below is an example of a summary I wrote for one of my past clients, 35 months of age.

AN’s ability to use language was assessed via the administration of the Language Use Inventory (LUI). The LUI is a standardized parental questionnaire for children ages 18-47 months aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development. Composed of 3 parts and 14 subscales it focuses on how the child communicates with gestures, words and longer sentences.

On the LUI, AN obtained a raw score of 53 and a percentile rank of <1, indicating profoundly impaired performance in the area of language use. While AN scored in the average range in the area of varied word use, deficits were noted with requesting help, word usage for notice, lack of questions and comments regarding self and others, lack of reciprocal word usage in activities with others, humor relatedness, adapting to conversations to others, as well as difficulties with building longer sentences and stories.

Based on above results AN presents with significant social pragmatic language weaknesses characterized by impaired ability to use language for a variety of language functions (initiate, comment, request, etc), lack of reciprocal word usage in activities with others, humor relatedness, lack of conversational abilities, as well as difficulty with spontaneous sentence and story formulation as is appropriate for a child his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve AN’s social pragmatic abilities.

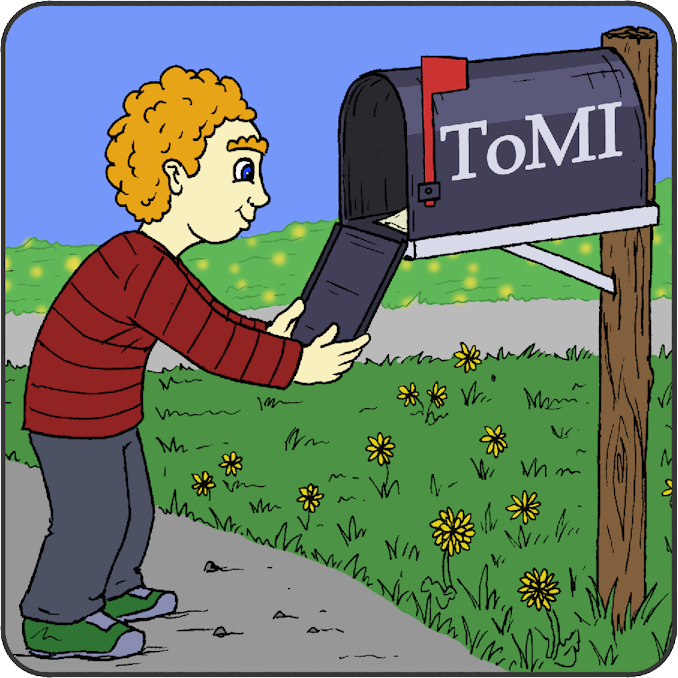

In addition to the LUI, I recently discovered the Theory of Mind Inventory-2. The ToMI-2 was developed on a normative sample of children ages 2 – 13 years. For children between 2-3 years of age, it offers a 14 question Toddler Screen (shared here with author’s permission). While due to the recency of my discovery, I have yet to use it on an actual client, I did have fun creating a report with it on a fake client.

In addition to the LUI, I recently discovered the Theory of Mind Inventory-2. The ToMI-2 was developed on a normative sample of children ages 2 – 13 years. For children between 2-3 years of age, it offers a 14 question Toddler Screen (shared here with author’s permission). While due to the recency of my discovery, I have yet to use it on an actual client, I did have fun creating a report with it on a fake client.

First, I filled out the online version of the 14 question Toddler Screen (paper version embedded in the link above for illustration purposes). Typically the parents are asked to place slashes on the form in relevant areas, however, the online version requested that I use numerals to rate skill acquisition, which is what I had done. After I had entered the data, the system generated a relevant report for my imaginary client. In addition to the demographic section, the report generated the following information (below):

- A bar graph of the client’s skills breakdown in the developed, undecided and undeveloped ranges of the early ToM development scale.

- Percentile scores of how the client did in the each of the 14 early ToM measures

- Median percentiles of scores

- Table for treatment planning broken down into strengths and challenges

I find the information provided to me by the Toddler Screen highly useful for assessment and treatment planning purposes and definitely have plans on using this portion of the TOM-2 Inventory as part of my future toddler evaluations.

Of course, the above instruments are only two of many, aimed at assessing social pragmatic abilities of children under 3 years of age, so I’d like to hear from you! What formal and informal instruments are you using to assess social pragmatic abilities of children under 3 years of age? Do you have a favorite one, and if so, why do you like it?

References:

- Hedberg, N.L., & Westby, C.E. (1993). Analyzing story-telling skills: Theory to practice. AZ: Communication Skill Builders.

- Mundy P, Block J, Delgado C, Pomares Y, Vaughan Van Hecke A, Parlade MV. (2007) Individual Differences and the Development of Joint Attention in Infancy. Child Development. 78:938–954

- LaRocque, M., & Leach, D. (2009). Increasing social reciprocity in young children with Autism. Intervention in School and Clinic, 10(5), 1-7.

- O’Neill, D. (2009). Language Use Inventory: An assessment of young children’s pragmatic language development for 18- to 47-month-old children [Manual]. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Knowledge in Development

- Tomasello, M. (1995). Joint attention as social cognition. In C. Moore, & P. J. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention: It’s origins and role in development (pp. 103–130). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Walden, T., & Ogan, T. (1988). The development of social referencing. Child Development, 59, 1230-1240.

- Westby, C. & Robinson, L. (2014). A developmental perspective for promoting theory of mind. Topics in

Language Disorders, 34(4), 362-383.

Early Intervention Evaluations PART III: Assessing Children Under 2 Years of Age

In this post, I am continuing my series of articles on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first installment in this series offered suggestions regarding what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, while my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders.

In this post, I am continuing my series of articles on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first installment in this series offered suggestions regarding what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, while my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders.

Today, I’d like to describe what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age. As I mentioned in my previous posts, the bulk of children I assess under the age of 3, are typically aged 30 months or older. However, a relatively small number of children are brought in for an assessment around an 18-month mark, which is the age group that I would like to discuss today.

Typically, these children are brought in due to a lack of or minimal speech-language production. Interestingly enough, based on the feedback of colleagues, this group is surprisingly hard to report on. While all SLPs will readily state that 18-month-old children are expected to have a verbal vocabulary of at least 50 words and begin to combine them into two-word utterances (e.g., ‘daddy eat’). When prompted: “Well, what else should my child be capable of?” many SLPs draw a blank regarding what else to say to parents on the spot.

As mentioned in my previous post on assessment of children under 3, the following sections should be an integral part of every early intervention speech-language assessment:

As mentioned in my previous post on assessment of children under 3, the following sections should be an integral part of every early intervention speech-language assessment:

- Background History

- Language Development and Use (Free Questionnaires)

- Adaptive Behavior

- Play Assessment (Westby, 2000) (Westby Play Scale-Revised Link)

- Auditory Function

- Oral Motor Exam

- Feeding and Swallowing

- Vocal Parameters

- Fluency and Resonance

- Articulation and Phonology

- Phonetic inventory

- Phonotactic Repertoire

- Speech intelligibility

- Phonological Processes Analysis (Independent and Relational)

- Receptive Language

- Expressive Language

- Social Emotional Development

- Pragmatic Language

- Impressions

- Recommendations

- Suggested Therapy Goals

- References (if pertinent to a particular report)

In my two previous posts, I’ve also offered examples of select section write-ups (e.g., receptive, expressive phonology, etc.). Below a would like to offer a few more for this age group. Below is an example of a write-up on an 18-month-old bilingual child with a very limited verbal output.

RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE:

L’s receptive language skills were solid at 8 months of age (as per clinical observations and REEL-3 findings) which is significantly below age-expectancy for a child her age (18 months). During the assessment L received credit for appropriately reacting to prohibitive verbalizations (e.g., “No”, “Stop”), attending to speaker when her name was spoken, performing a routine activity upon request (when combined with gestures), looking at familiar object when named, finding the aforementioned familiar object when not in sight, as well as pointing to select body parts on Mrs. L and self (though identification on self was limited). L is also reported to be able to respond to yes/no questions by head nods and shakes.

However, during the assessment L was unable to consistently follow 1 and 2 step directions without gestural cues, understand and perform simple actions per clinician’s request, select objects from a group of 3-5 items given a verbal command, select familiar puzzle pieces from a visual field of 2 choices, understand simple ‘wh questions (e.g., “what?”, “where?”), point to objects or pictures when named, identify simple pictures of objects in book, or display the knowledge and understanding of age appropriate content, function and early concept words (in either Russian or English) as is appropriate for a child her age.

EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE and ARTICULATION

L’s expressive language skills were judged to be solid at 7 months of age (as per clinical observations and REEL-3 findings), which is significantly below age-expectancy for a child her age (18 months). L was observed to spontaneously use proto-imperative gestures (eye gaze, reaching, and leading [by hand]), vocalizations, as well waving for the following language functions: requesting, rejecting, regulating own environment as well as providing closure (waving goodbye).

L’s spontaneous vocalizations consisted primarily of reduplicated babbling (with a limited range of phonemes) which is significantly below age-expectancy for a child her age (see below for developmental norms). During the assessment, L was observed to frequently vocalize “da-da-da”. However, it was unclear whether she was vocalizing to request objects (in Russian “dai” means “give”) due to the fact that she was not observed to consistently vocalize the above solely when requesting items. Additionally, L was not observed to engage in reciprocal babbling or syllable/word imitation during today’s assessment, which is a concern for a child her age. When the examiner attempted to engage L in structured imitation tasks by offering and subsequently denying a toy of interest until L attempted to imitate the desired sound, L became easily frustrated and initiated tantrum behavior. During the assessment, L was not observed to imitate any new sounds trialed with her by the examiner.

During today’s assessment, L’s primary means of communication consisted of eye gaze, reaching, crying, gestures, as well as sound and syllable vocalizations. L’s phonetic inventory consisted of the following consonant sounds: plosives (/p/, /b/ as reported by Mrs. L), alveolars (/t/, /d/ as reported and observed), fricative (/v/ as observed), velar (/g/ as observed), as well as nasal (/n/, and /m/ as observed). L was also observed to produce two vowels /a/ and a pharyngeal /u/. L’s phonotactic repertoire was primarily restricted to reported CV(C-consonant; V-vowel) and VCV syllable shapes, which is significantly reduced for a child her age.

According to developmental norms, a child of L’s age (18 months) is expected to produce a wide variety of consonants (e.g., [b, d, m, n, h, w] in initial and [t, h, s] in final position of words) as well as most vowels. (Robb, & Bleile,(1994); Selby, Robb & Gilbert, 2000). During this time the child’s vocabulary size increases to 50+ words at which point children begin to combine these words to produce simple phrases and sentences (as per Russian and English developmental norms). Additionally, an, 18 months old child is expected to begin monitoring and repairing own utterances, adjusting speech to different listeners, as well as practicing sounds, words, and early sentences. (Clark, adapted by Owens, 2015)

Based on the above guidelines L’s receptive and expressive language, as well as articulation abilities, are judged to be significantly below age expectancy at this time. Speech and language therapy is strongly recommended in order to improve L’s speech and language skills.

Typically when the assessed young children exhibit very limited comprehension and expression, I tend to provide their caregivers with a list of developmental expectations for that specific age group (given the range of a few months) along with recommendations of communication facilitation. Below is an example of such a list, pulled a variety of resources.

Developmental Milestones expected of a 16-18 months old toddler:

Developmental Milestones expected of a 16-18 months old toddler:

Attention/Gaze:

- Make frequent spontaneous eye contact with adults during interactions

- Turn head to look towards the new voice, when another person begins to talk

- Make 3-point gaze shifts by 1. looking at a toy in hand, 2. then at an adult, 3. then back to the toy

- Make 4-point gaze shifts if more than one person is in the room – by looking from a toy in hand to one person, then the other person, then back to the toy,

- Spontaneously attend to book, activity for 2-3+ minutes without redirection

Reaching and Gestures:

- Show objects in hand to an adult (without actually giving them)

- Push away items that aren’t wanted

- Engage in give and take games when holding objects with an adult

- Imitate simple gestures such as clapping hands or waving bye-bye

- Hand an object to an adult to ask for help with it

- Shake head “no?”

Play Skills/Routines:

Play Skills/Routines:

- Attempt to actively explore toys (e.g., push or spin parts of toys, turn toys over, roll them back and forth)

- Repeat interesting actions with toys (e.g., make a toy produce an unusual noise, then attempt to make the noise again)

- Imitate simple play activities (adult bangs two blocks together, then child imitates)

- Use objects on daily basis (e.g., when given a spoon or cup the child attempts to feed himself. When putting on clothes the child begins to lift his arms in anticipation of a shirt going on.)

Receptive (Listening Skills):

- Consistently follow 1 and 2 step directions without gestural cues

- Understand and perform simple actions per request (“sit down” or “come here”) without gestures

- Select objects from a group of 3 items given a verbal command

- Select familiar puzzle pieces from a visual field of 2 choices

- Understand simple ‘wh questions (e.g., “what?”, “where?”)

- Point to objects or pictures when named

- Spontaneously and consistently identify simple pictures of objects in book

- Stop momentarily what he is doing if an adult says “no” in a firm voice

- Identify 2-3 common everyday objects or body parts when asked

Expressive (Speaking Skills):

- Produce a wide variety of consonants (e.g., [b, d, m, n, h, w] in initial and [t, h, s] in final position of words) as well as most vowels. (Robb, & Bleile,(1994); Selby, Robb & Gilbert, 2000).

- Have a vocabulary size nearing 50 words (e.g., 35-40)

- Imitate adult words or vocalizations

- Attempt to practice sounds and words (Clark, adapted by Owens, 2015)

- Appropriately label familiar objects (foods, toys, animals)

Materials to use with the child to promote language and play:

Materials to use with the child to promote language and play:

- Bubbles

- Cause and effect toys

- Toys with a variety of textures (soft toys, plastic toys, cardboard blocks, ridged balls)

- Toys with multiple actions

- Toys with special effects: lights, sounds, movement (push and go vehicles)

- Building and linking toys

- Toys with multiple parts

- Balls, cars and trucks, animals, dolls

- Puzzles

- Pop-up picture books

- Toys the child demonstrates an interest in (parents should advise)

Strategies:

- Reduce distractions (noise, clutter etc)

- Provide one on one interaction in a structured space (e.g., sitting at the play table or sitting on parent’s lap) to improve attention

- Offer favorite activities and toys of interest initially before branching out to new materials

- Offer favorite foods/toys as reinforcers to continue working

- Offer choices of two toys, then remove one toy and focus interaction with one toy of interest

- Try to prolong attention to toy for several minutes at a time

- Change activities frequently, HOWEVER, repeat same activities in cycles over and over again during home practice in order to solidify skills

- Label objects and actions in the child’s immediate environment

- Use brief but loud utterances (2-3 words not more) to gain attention and understanding

- Frequently repeat words in order to ensure understanding of what is said/expected of child

- Use combination of gestures, signs, words, and pictures to teach new concepts

- Do not force child to speak if he doesn’t want to rather attempt to facilitate production of gestures/sounds (e.g., use “hand over hand” to show child the desired gesture such as pointing/waving/motioning in order to reduce his/her frustration

- Use play activities as much as possible to improve child’s ability to follow directions and comprehend language

- Doll House (with Little People)

- Garage

- Farm, etc

Core vocabulary categories for listening and speaking:

Core vocabulary categories for listening and speaking:

- Favorite and familiar toys and objects

- Names of people in the child’s life as well as his own name

- Pets

- Favorite or familiar foods

- Clothing

- Body parts

- Names of daily activities and actions (go, fall, drink, eat, walk, wash, open)

- Recurrence (more)

- Names of places (bed, outside)

- Safety words (hot, no, stop, dangerous, hurt, don’t touch, yuck, wait)

- Condition words (boo-boo, sick/hurt, mad, happy)

- Early pronouns (me, mine)

- Social words (hi, bye, please, sorry)

- Early concepts: in, off, on, out, big, hot, one, up, down, yucky, wet, all done)

- Yes/no

Select References:

- Owens, R. E. (2015). Language development: An introduction (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Rescorla, L. (1989). The Language Development Survey: A screening tool for delayed language in toddlers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 587–599.

- Rescorla, L., Hadicke-Wiley, M., & Escarce, E. (1993). Epidemiological investigation of expressive language delay

at age two. First Language, 13, 5–22. - Robb, M. P., & Bleile, K. M. (1994). Consonant inventories of young children from 8 to 25 months. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 8, 295-320.

- Selby, J. C., Robb, M. P., & Gilbert, H. R. (2000). Normal vowel articulations between 15 and 36 months of age. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 14, 255-266.

Click HERE for the Early Intervention Evaluations PART IV: Assessing Pragmatic Abilities of Children Under 3

Stay Tuned for the next installment in this series:

- Early Intervention Evaluations PART V: Assessing Feeding and Swallowing in Children Under Two

Early Intervention Evaluations PART II: Assessing Suspected Motor Speech Disorders in Children Under 3

In my previous post on this topic, I brought up concerns regarding the paucity of useful information in EI SLP reports for children under 3 years of age and made some constructive suggestions of how that could be rectified. In 2013, I had written about another significant concern, which involved neurodevelopmental pediatricians (rather than SLPs), diagnosing Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS), without the adequate level of training and knowledge regarding motor speech disorders. Today, I wanted to combine both topics and delve deeper into another area of EI SLP evaluations, namely, assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders.

Firstly, it is important to note that CAS is disturbingly overdiagnosed. A cursory review of both parent and professional social media forums quickly reveals that this diagnosis is doled out like candy by both SLPs and medical professionals alike, often without much training and knowledge regarding the disorder in question. The child is under 3, has a limited verbal output coupled with a number of phonological processes, and the next thing you know, s/he is labeled as having Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS). But is this diagnosis truly that straightforward?

Let us begin with the fact that all reputable organizations involved in the dissemination of information on the topic of CAS (e.g., ASHA, CASANA, etc.), strongly discourage the diagnosis of CAS in children under three years of age with limited verbal output, and limited time spent in EBP therapy specifically targeting the remediation of motor speech disorders.

Assessment of motor speech disorders in young children requires solid knowledge and expertise. That is because CAS has a number of overlapping symptoms with other speech sound disorders (e.g., severe phonological disorder, dysarthria, etc). Furthermore, symptoms which may initially appear as CAS may change during the course of intervention by the time the child is older (e.g., 3 years of age) which is why diagnosing toddlers under 3 years of age is very problematic and the use of “suspected” or “working” diagnosis is recommended (Davis & Velleman, 2000) in order to avoid misdiagnosis. Finally, the diagnosis of CAS is also problematic due to the fact that there are still to this day no valid or reliable standardized assessments sensitive to CAS detection (McCauley & Strand, 2008).

Assessment of motor speech disorders in young children requires solid knowledge and expertise. That is because CAS has a number of overlapping symptoms with other speech sound disorders (e.g., severe phonological disorder, dysarthria, etc). Furthermore, symptoms which may initially appear as CAS may change during the course of intervention by the time the child is older (e.g., 3 years of age) which is why diagnosing toddlers under 3 years of age is very problematic and the use of “suspected” or “working” diagnosis is recommended (Davis & Velleman, 2000) in order to avoid misdiagnosis. Finally, the diagnosis of CAS is also problematic due to the fact that there are still to this day no valid or reliable standardized assessments sensitive to CAS detection (McCauley & Strand, 2008).

In March 2017, Dr. Edythe Strand wrote an excellent article for the ASHA Leader entitled: “Appraising Apraxia“, in which she used a case study of a 3-year-old boy to describe how a differential diagnosis for CAS can be performed. She reviewed CAS characteristics, informal assessment protocols, aspects of diagnosis and treatment, and even included ‘Examples of Diagnostic Statements for CAS’ (which illustrate how clinicians can formulate their impressions regarding the child’s strengths and needs without explicitly labeling the child’s diagnosis as CAS).

Today, I’d like to share what information I tend to include in speech-language reports geared towards the assessing motor speech disorders in children under 3 years of age. I have a specific former client in mind for whom a differential diagnosis was particularly needed. Here’s why.

This particular 30-month client, TQ, (I did mention that I get quite a few clients for assessment around that age), was brought in due to parental concerns over her significantly reduced speech and expressive language abilities characterized by unintelligible “babbling-like” utterances and lack of expressive language. All of TQ’s developmental milestones with the exception of speech and language had been achieved grossly at age expectancy. She began limitedly producing word approximations at ~16 months of age but at 30 months of age, her verbal output was still very restricted. She mainly communicated via gestures, pointing, word approximations, and a handful of signs.

Interestingly, as an infant, she had a restricted lingual frenulum. However, since it did not affect her ability to feed, no surgical intervention was needed. Indeed, TQ presented with an adequate lingual movement for both feeding and speech sound production, so her ankyloglossia (or anterior tongue tie) was definitely not the culprit which caused her to have limited speech production.

Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion.

Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion.

Assessment of TQ’s social-emotional functioning, play skills, and receptive language (via a combination of Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), REEL-3, & PLS-5) quickly revealed that she was a very bright little girl who was developing on target in all of the tested areas. Assessment of TQ’s expressive language (via REEL-3, PLS-5 & LUI*), revealed profoundly impaired, expressive language abilities. But due to which cause?

Despite lacking verbal speech, TQ’s communicative frequency (how often she attempted to spontaneously and appropriately initiate interactions with others), as well as her communicative intent (e.g., gaining attention, making requests, indicating protests, etc), were judged to be appropriate for her age. She was highly receptive to language stimulation given tangible reinforcements and as the assessment progressed she was observed to significantly increase the number and variety of vocalizations and word approximations including delayed imitation of words and sounds containing bilabial and alveolar nasal phonemes.

For the purpose of TQ’s speech assessment, I was interested in gaining knowledge regarding the following:

- Automatic vs. volitional control

- Simple vs. complex speech production

- Consistency of productions on repetitions of the same words/word approximations

- Vowel Productions

- Imitation abilities

- Prosody

- Phonetic inventory

- Phonotactic Constraints

- Stimulability

TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output.

TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output.

- Phonetic inventory of all the sounds TQ produced during the assessment is as follows:

- Consonants: plosive nasals (/m/) and alveolars (/t/, /d/, n), as well as a glide (/w/)

- Vowels: (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/)

- TQ’s phonotactic repertoire was primarily comprised of word approximations restricted to specific sounds and consisted of CV (e.g., ne), VCV (e.g., ada), CVC (e.g., nyam), CVCV (e.g., nada), VCVC (e.g., adat), CVCVCV (nadadi), VCVCV(e.g., adada) syllable shapes

- TQ’s speech intelligibility in known and unknown contexts was profoundly reduced to unfamiliar listeners. However, her word approximations were consistent across all productions.

- Due to the above I could not perform an in-depth phonological processes analysis

However, by this time I had already formulated a working hypothesis regarding TQ’s speech production difficulties. Based on her speech sound assessment TQ presented with severe phonological disorder characterized by restricted sound inventory, simplification of sound sequences, as well as patterns of sound use errors (e.g., predominance of alveolar /d/ and nasal /n/ sounds when attempting to produce most word approximations) in speech (Stoel-Gammon, 1987).

TQ’s difficulties were not consistent with the diagnosis Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS) at that time due to the following:

- Adequate and varied production of vowels

- Lack of restricted use of syllables during verbalizations (TQ was observed to make verbalizations up to 3 syllables in length)

- Lack of disruptions in rate, rhythm, and stress of speech

- Frequent and spontaneous use of consistently produced verbalizations

- Lack of verbal groping behaviors when producing word-approximations

- Good control of pitch, loudness and vocal quality during vocalizations

I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made.

I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made.

I still, however, wanted to be cautious as there were a few red flags I had noted which may have potentially indicative of a non-CAS motor speech involvement, due to which I wanted to include some recommendations pertaining to motor speech remediation.

Now it is possible that after 6 months of intensive application of EBP phonological and motor speech approaches TQ would have turned 3 and still presented with highly restricted speech sound inventory and profoundly impaired speech production, making her eligible for the diagnosis of CAS in earnest. However, at the time of my assessment, making such diagnosis in view of all the available evidence would have been both clinically inappropriate and unethical.

So what were my recommendations you may ask? Well, I provisionally diagnosed TQ with a severe phonological disorder and recommended that among a variety of phonologically-based approaches to trial, an EBP approach to the treatment of motor speech disorders be also used with her for a period of 6 months to determine if it would expedite speech gains.

*For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the Rapid Syllable Transition Treatment (ReST). ReST is a free EBP treatment developed by the SLPs at the University of Sydney, which uses nonsense words, designed to help children coordinate movements across syllables in long words and phrases as well as helps them learn new speech movements. It is, however, important to note for young children with highly restricted sound inventories, characterized by a lack of syllable production, ReST will not be applicable. For them, the Integral Stimulation/Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC) approaches do have some limited empirical support.

*For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the Rapid Syllable Transition Treatment (ReST). ReST is a free EBP treatment developed by the SLPs at the University of Sydney, which uses nonsense words, designed to help children coordinate movements across syllables in long words and phrases as well as helps them learn new speech movements. It is, however, important to note for young children with highly restricted sound inventories, characterized by a lack of syllable production, ReST will not be applicable. For them, the Integral Stimulation/Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC) approaches do have some limited empirical support.

I also made sure to make a note in my report regarding the inappropriate use of non-speech oral motor exercises (NSOMEs) in therapy, indicating that there is NO research to support the use of NSOMEs to stimulate speech production (Lof, 2010).

In addition to the trialing of phonological and motor based approaches I also emphasized the need to establish consistent lexicon via development of functional words needed in daily communication and listed a number of examples across several categories. I made recommendations regarding select approaches and treatment techniques to trial in therapy, as well as suggestions for expansion of sounds and structures. Finally, I made suggestions for long and short term therapy goals for a period of 6 months to trial with TQ in therapy and provided relevant references to support the claims I’ve made in my report.

You may be interested in knowing that nowadays TQ is doing quite well, and at this juncture, she is still, ineligible for the diagnosis CAS (although she needs careful ongoing monitoring with respect to the development of reading difficulties when she is older).

Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of questionable and even downright harmful bunk treatments for their children, the treatment may only be limitedly appropriate, and may not result in the best possible outcomes for a particular child. To illustrate, TQ never presented with CAS and as such, while she may have initially limitedly benefited from the application of motor speech principles to address her speech production, shortly thereafter, the application of the principles of the dynamic systems theory is what brought about significant changes in her phonological repertoire.

Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of questionable and even downright harmful bunk treatments for their children, the treatment may only be limitedly appropriate, and may not result in the best possible outcomes for a particular child. To illustrate, TQ never presented with CAS and as such, while she may have initially limitedly benefited from the application of motor speech principles to address her speech production, shortly thereafter, the application of the principles of the dynamic systems theory is what brought about significant changes in her phonological repertoire.

That is why the correct diagnosis is so important for young children under 3 years of age. But before it can be made, extensive (reputable and evidence supported) training and education are needed by evaluating SLPs on the assessment and treatment of motor speech disorders in young children.

References:

- Davis, B & Velleman, S (2000). Differential diagnosis and treatment of developmental apraxia of speech in infants and toddlers”. The Transdisciplinary Journal. 10 (3): 177 – 192.

- Lof, G., & Watson, M. (2010). Five reasons why nonspeech oral-motor exercises do not work. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 11.109-117.

- McCauley RJ, Strand EA. (2008). A Review of Standardized Tests of Nonverbal Oral and Speech Motor Performance in Children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17,81-91.

- McCauley R.J., Strand E., Lof, G.L., Schooling T. & Frymark, T. (2009). Evidence-Based Systematic Review: Effects of Nonspeech Oral Motor Exercises on Speech, American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 343-360.

- Murray, E., McCabe, P. & Ballard, K.J. (2015). A Randomized Control Trial of Treatments for Childhood Apraxia of Speech. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research 58 (3) 669-686.

- Stoel-Gammon, C. (1987). Phonological skills of 2-year-olds. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 18, 323-329.

- Strand, E (2003). Childhood apraxia of speech: suggested diagnostic markers for the young child. In Shriberg, L & Campbell, T (Eds) Proceedings of the 2002 childhood apraxia of speech research symposium. Carlsbad, CA: Hendrix Foundation.

- Strand, E, McCauley, R, Weigand, S, Stoeckel, R & Baas, B (2013) A Motor Speech Assessment for Children with Severe Speech Disorders: Reliability and Validity Evidence. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, vol 56; 505-520.