I’ve been meaning to write this post for some time and have finally decided to do it now due to an increased prevalence of “non-traditional” treatment options available to parents of language impaired children.

I’ve been meaning to write this post for some time and have finally decided to do it now due to an increased prevalence of “non-traditional” treatment options available to parents of language impaired children.

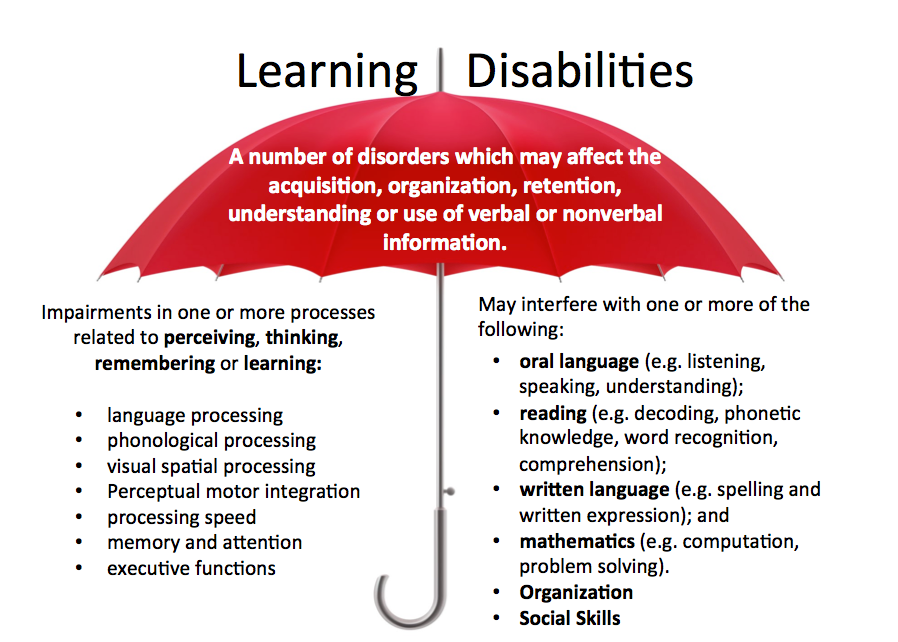

More and more unscrupulous or misguided individuals are offering fantastical cures to children diagnosed with the wide variety of disorders including but not limited to: Autism (ASD), Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS), language disorders, “Auditory Processing Deficits (APD)“, Dyslexia, and much much more.

What are some examples of controversial products and therapies you may ask?

Below I cite several links (which are in no way exhaustive) for your convenience.

Controversial Autism Treatments:

In 2013, Dr. Emily Willingham, guest writer for Forbes magazine wrote a post on the topic of “The 5 Scariest Autism ‘Treatments. In it she described some pretty horrifying methods (e.g., chelation, chemical castration, hyperbaric oxygen therapy) which purportedly promised to “cure” autism. For more information on other controversial treatments in autism click to read this keynote address entitled Evidence-Based Practices for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders by Dr. Tristram Smith for The Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (SCCAP).

Controversial Speech Sound Disorder Treatments

Dr. Caroline Bowen respected Speech Language Researcher from Australia has a delightfully edifying page on her website (http://speech-language-therapy.com/) entitled: “Controversial Practices in Children’s Speech Sound Disorders – Oral Motor Exercises, Dietary Supplements, Auditory Integration Training”. On it she thoroughly reviews non-research supported practices to improve children’s sound production including the use of oral motor/mouth exercises, dietary supplements (Apraxia Diet, Nourish Life Speak, Nutri Veda, etc.), as well as Auditory Integration Training (AIT).

Parent‐Friendly Information about Nonspeech Oral Motor Exercises (HERE)

Controversial Treatments for Children with Developmental and Learning Disabilities

Macquarie University Special Education Centre in Sydney Australia has even developed concise one-page briefings of a vast number of controversial treatments for children with developmental and learning disabilities (selected briefing links are below; the full list of briefings is available HERE):

- Behavioural Optometry

- Learning Styles

- Fast ForWord Language

- Cellfield Program

- The Listening Program

- Irlen Tinted Lenses and Overlays

How to Spot Controversial Practices?

In her 2012 post entitled: “10 Questions To Distinguish Real From Fake Science“, Dr. Emily Willingham wrote that “science consumers need a cheat sheet … when considering a product, book, therapy, or remedy”. She advised consumers to consider some of the following criteria:

- Consider the source

- Determine their agenda

- Do they use highly emotionally charged language or meaningless jargon?

- Are they relying on testimonials vs. evidence?

- Are they claiming to be exclusive?

- Do they mention words like ‘conspiracy’?

- Is their treatment promising to cure multiple unrelated disorders?

- What does the money trail reveal?

The truth is that there’s a lot of pseudoscience out there and as such it is very important for both parents and professionals not to fall into its trap. In 2012, Dr. Gregory Lof presented the following poster at the ASHA’s Atlanta Convention: “Science vs. Pseudoscience in CSD: A Checklist for Skeptical Thinking” to “help clinicians evaluate claims made by promoters of products or services to help determine if they are based on scientific principles or on pseudoscience”. An interactive version of the checklist is available HERE, and for the summary based on the checklist, written by Mary Huston, fellow SLP and author of the Speech Adventures, click HERE.

So what do pseudoscientific practices/claims look like?

- People place heavy emphasis on beliefs and opinions vs. data, when it comes to therapeutic claims

- SLPs: “You are wrong! I’ve seen ________ work with my clients!”

- Parents: “Who cares about your research this _______worked for us so HOW DARE YOU question it?

- The presented data is based on “expert opinions”, testimonials, and isolated case studies

- “These ridiculously expensive ‘speech sticks’ at $120 a pop worked for us, Yay!”

- Data is disseminated via self-published books, popular press, proprietary websites lacking research sections, as well as non-peer reviewed conferences.

- You might want to review the list of predatory publishers HERE, review the guide of how to spot a bogus scientific publication HERE, and if you ever find yourself reading anything on this website, I suggest you close your laptop as fast as you can and possibly put it into another room for a while (Read Why – HERE).

- Treatment sounds like a magic potion since it works on a wide range of disabilities, appeals to fears and wishful thinking, preys on the desperate and uses hyperboles (“miracle cure”)

- Use of disdainful comments against researchers because “only clinicians do real clinical work”coupled with over reliance on clinician’s experience and subjective judgment since it’s the “best way” to determine effectiveness

- “I’ve found ___________ to be highly effective with gazillion clients”.

- Lack of change in practices despite a veritable mountain of evidence to the contrary

- “Your child NEEDS oral-motor exercises, NOW, for his speech to get better”

- New terms are created to mask use of disproven pseudoscientific practices

Why do we keep believing when all the evidence points to the contrary?

Because our brains become emotionally attached to ideas. This is further supported by the construct of two biases.

Confirmation bias – our tendency to look for/interpret information in a way that confirms our beliefs by “cherry picking” the evidence that supports what we believe in and ignoring the evidence that argues against it.

Disconfirmation bias – when facing with evidence which directly contradicts our beliefs we will criticize and reject it because we do not want to be wrong.

So now let’s get back to talk about the title of this post: “What’s the harm in that?”

While I am accustomed to seeing the variation of this statement on parent forums, I was surprised when I learned that it’s popping up quite often in some unexpected places such as during IEP meetings or during doctor visits (as reported to me by some of my client’s parents).

So I wanted to take this opportunity to explicitly point out what the harm in these alternative practices could be, ranging from the obvious to the hidden.

For starters some of these ‘therapies’ could kill!

- Over the years there has been a number of reports regarding deaths from controversial autism treatments including chelation and GcMAF injections.

Even if they don’t kill you they can cause some nasty side effects!

- To illustrate, Nourish Life Speak Nutrients, which were prescribed to children to “increase their language output or to make them speak better”, were so loaded with vitamin E (way above the legal amount), that a number of children who were taking them experienced significant seizure activity.

It’s going to cost you!

- Out of sheer desperation, families will spend tens of thousands of dollars on ‘alternative’ treatments which are ineffective at best and harmful at worst. To illustrate via a fairly benign example. Here’s the typical question that can be seen on a variety of parent forums pertaining to therapies for “(C) APD”: Q: My nine-year-old was diagnosed with mild auditory processing problems and ADHD, inattentive type. It was recommended that she do Fast ForWord. This is very expensive — $3,500 in the office and $1,100 at home. Does this program work and is there a benefit to doing it in the office? I would hate to spend $3,500 for nothing. The problem is that “systematic reviews found no sign of a reliable effect of Fast ForWord® on reading or on expressive or receptive spoken language.” So where does that leave the parents who spend thousands of dollars on this program in hopes that it really will improve oral language and reading abilities of their children? This leads me to my next point.

They create false hope!

- Whether it’s a placebo or the Hawthorne effect, or just a desperate desire to believe that something is working after you have sank so much hope, time, money, and energy into it, it may look like ineffective treatments are working at least for a short period of time. However, sooner or later parents start to notice that the issues whatever they may be continue to persist or even worsen despite the provided treatment. To illustrate, let’s take an example of a child with severe speech delay who is prescribed oral motor exercises to improve their speech production. At first, it appears that doing tongue curls, blowing kazoos, and chewing on bite blocks appears to be working and the child’s speech seems more intelligible. However, soon the parents may realize that while this expensive treatment is taking a significant period of time to complete the child’s speech production did not functionally improve since the therapist did not work directly on increasing the child’s repertoire of sounds and words.

They can create a sense of bitterness and hopelessness!

- Ever spoken to parents who have tried every alternative treatment possible and have subsequently given up? If you haven’t, I assure you it’s not a pleasant or productive conversation. At best you will hear a lot of vitriol and accusations and at worst they may actually start a forum thread or a website bashing effective treatments such as speech language therapy because of their negative experiences. When you believe that you have tried everything and it’s still not helping, you feel defeated and lost and as a result tend to attack blindly anyone who attempts to assist you because you’ve stopped perceiving it as assistance but rather as just another scam.

They delay effective research-proven treatments!

- Last week I wrote a blog post entitled: “Why (C) APD Diagnosis is NOT Valid!” citing the latest research literature to explain that the controversial diagnosis of APD tends to a) detract from understanding that the child presents with legitimate language based deficits in the areas of comprehension, expression, social communication and literacy development and b) may result in the above deficits not getting adequately addressed due to the provision of controversial APD treatments. In other words I was in NO way trying to disprove that the processing deficits exhibited by the children diagnosed with “APD” were not real. Rather I was trying to point out that these processing deficits are due to a different cause – namely a language disorder which has turned into a language disability and as such needed to be addressed by linguistic rather than ‘auditory’ therapies. In other words what research has found you can get auditory therapies indefinitely and with great frequency but they would still NOT generalize to improve the child’s language abilities (including reading) in the affected areas. The problem is that by delaying legitimate therapies (e.g., in the above case evidence-based reading intervention for the student) there is a significant risk of poorer social and academic outcomes as the child grows older.

They affect self-esteem and self-efficacy!

- Now enough about parents and professionals. Let’s actually take a moment to talk about effect of these alternative practices on the most important people in question: the children who are on the receiving end of it! Let’s talk about all the negative effects that can be incurred by them by undergoing these useless treatments time after time. And no I am not actually talking about the hugely dangerous treatments, which can cause physical harm or awful side effects. I am talking about the relatively benign treatments of “vision therapy”, “memory training”, etc.

- To illustrate, I work with are very bright 11-year-old boy with significant reading deficits and an extensive history of reading disabilities in the family. This boy’s deficit is in the area of reading, there is no doubt about it! He knows it and it’s very acutely aware of it. However, at the advice of well-meaning professionals he was taken to a behavioral optometrist, who told his mother that his issues with reading are due to visual processing deficits (despite the fact that his ophthalmologist ruled out any vision difficulties and declared his vision to be 20/20). It was then recommended that he undergo a costly vision therapy program in order to improve his “visual processing”. Guess, what his first words were, when I saw him in my office for reading intervention? ‘I went to the doctor who told me that I have problems in my eyes and that I need to stop reading! So I can’t do any more reading because of my eye problems.’ Imagine how he will feel when after several months of costly therapies there will be no functional improvement in his reading skills, since the only thing which can improve his reading abilities is the actual targeted reading instruction!

- Our students are very acutely aware when something is not working. Just like us they get increasingly frustrated after being dragged from one professional to another, after ‘suffering’ through one controversial treatment after another with no respite in sight. Imagine what havoc it begins to wreak on their self-esteem and their self-efficacy (belief in own abilities to complete tasks and reach goals), when they keep undergoing these treatments without any improvement? All the negative self-talk they will use? Here are just a few statements I’ve heard over the years: “I am so stupid”; “There’s something wrong with my brain”, “I am not good at this, etc.) Instead of building them up these alternative therapies and treatments will not just tear them back down but may potentially cause behavioral and psychiatric effects to boot.

There you have it: that’s what the harm is! The toll of these quack practices can be very significant and can go far beyond the financial. So the next time someone utters the statement: “What’s the Harm in That?” consider the above information in order to make the informed decisions regarding the treatment for the most vulnerable parties involved: the children in your care!

There you have it: that’s what the harm is! The toll of these quack practices can be very significant and can go far beyond the financial. So the next time someone utters the statement: “What’s the Harm in That?” consider the above information in order to make the informed decisions regarding the treatment for the most vulnerable parties involved: the children in your care!

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for

Our ability to recognize our own and other people’s emotions, distinguish between and correctly identify different feelings, as well as use that information to guide our thinking and behavior is called Emotional Intelligence (EI) (Salovey, et al, 2008).

Our ability to recognize our own and other people’s emotions, distinguish between and correctly identify different feelings, as well as use that information to guide our thinking and behavior is called Emotional Intelligence (EI) (Salovey, et al, 2008).

One common difficulty our “higher functioning” (refers to subjective notion of ‘perceived’ functioning in school setting only) language impaired students with social communication and executive function difficulties present with – is lack of insight into own strengths and weaknesses.

One common difficulty our “higher functioning” (refers to subjective notion of ‘perceived’ functioning in school setting only) language impaired students with social communication and executive function difficulties present with – is lack of insight into own strengths and weaknesses.

Recently I read a terrific article written in 2014 by

Recently I read a terrific article written in 2014 by

.JPG)

Frequently, I see a variation of the following scenario on many speech and language forums.

Frequently, I see a variation of the following scenario on many speech and language forums. Let’s begin by answering a few simple questions. Was a thorough language evaluation with an emphasis on the child’s social pragmatic language abilities been completed? And by thorough, I am not referring to general language tests but to a variety of formal and informal social pragmatic language testing (read more

Let’s begin by answering a few simple questions. Was a thorough language evaluation with an emphasis on the child’s social pragmatic language abilities been completed? And by thorough, I am not referring to general language tests but to a variety of formal and informal social pragmatic language testing (read more  Please note that none of the general language tests such as the Preschool Language Scale-5 (PLS-5), Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL-2), the Test of Language Development-4 (TOLD-4) or even the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals Tests (CELF-P2)/ (CELF-5) tap into the child’s social language competence because they do NOT directly test the child’s social language skills (e.g., CELF-5 assesses them via a parental/teachers questionnaire). Thus, many children can attain average scores on these tests yet still present with pervasive social language deficits. That is why it’s very important to thoroughly assess social pragmatic language abilities of all children (no matter what their age is) presenting with behavioral deficits.

Please note that none of the general language tests such as the Preschool Language Scale-5 (PLS-5), Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (CASL-2), the Test of Language Development-4 (TOLD-4) or even the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals Tests (CELF-P2)/ (CELF-5) tap into the child’s social language competence because they do NOT directly test the child’s social language skills (e.g., CELF-5 assesses them via a parental/teachers questionnaire). Thus, many children can attain average scores on these tests yet still present with pervasive social language deficits. That is why it’s very important to thoroughly assess social pragmatic language abilities of all children (no matter what their age is) presenting with behavioral deficits.