As a speech-language pathologist (SLP) working with school-age children, I frequently assess students whose language and literacy abilities adversely impact their academic functioning. For the parents of school-aged children with suspected language and literacy deficits as well as for the SLPs tasked with screening and evaluating them, the concept of ‘academic impact’ comes up on daily basis. In fact, not a day goes by when I do not see a variation of the following question: “Is there evidence of academic impact?”, being discussed in a variety of Facebook groups dedicated to speech pathology issues.

As a speech-language pathologist (SLP) working with school-age children, I frequently assess students whose language and literacy abilities adversely impact their academic functioning. For the parents of school-aged children with suspected language and literacy deficits as well as for the SLPs tasked with screening and evaluating them, the concept of ‘academic impact’ comes up on daily basis. In fact, not a day goes by when I do not see a variation of the following question: “Is there evidence of academic impact?”, being discussed in a variety of Facebook groups dedicated to speech pathology issues.

At first glance, the issue of academic impact appears to be rather straightforward. For example, many SLPs will readily assert that if a child is receiving good grades (A’s and B’s) in the school setting and is not exhibiting any “significant” maladaptive and challenging behaviors, then there is no evidence of adverse academic impact, and screening/evaluation/intervention services are unnecessary.

Unfortunately, things are not as “crystal clear” as they appear. That is because of the relative subjectivity pertaining to the grading practices of the students’ work in the school setting. Now, before you accuse me of inventing a problem where there is none, please hear me out.

In this post, I would like to illustrate how the subjectivity of grading practices can obfuscate the issue of academic impact to such an extent that students with significant language and learning needs may not be identified as being in need of help until it’s far too late – if identified at Let’s begin with reading, an incredibly complex and deeply misunderstood process, especially in settings which do not utilize scientifically informed practices (e.g., synthetic phonics) when teaching young children to read. When it comes to the teaching and assessment of reading, it is an absolute Wild West out there! And no one is more familiar with it, than parents of reading impaired children.

One of the first things these parents notice about their children in the early grades is that their reading abilities are highly inconsistent and are not commensurate with those of their peers. These parents will notice that it takes their kids an extraordinary amount of time to master the alphabetic principle (remember the letters of the alphabet, match letters to sounds, etc.). They will notice that their children have an extraordinarily difficult time blending simple three letter words involving initial and final consonants with a medial vowel (e.g., “nob”). They will complain that their children display inconsistent knowledge of “sight words” from day to day, as well as misread and skip words when reading.

Here is the problem though, unless objective measures are used to test their children’s phonemic awareness and phonics abilities, there is a very strong possibility that these issues will persist well into upper elementary years, completely unnoticed in the school system, given the subjectivity involved in assessing reading mastery.

Indeed, numerous studies highlight the lack of efficacy of build-in assessments in programs such as Fountas and Pinnell, Reading Recovery, as well as the utility of utilizing Running Records, for reading assessment purposes. My clinical observations of struggling readers in a variety of school settings, as part of the independent evaluation process, certainly support and corroborate available research on the subject. Namely, in many educational disputes, there’s a significant mismatch between teacher claims “S/he is reading at grade level as per (insert subjective method here)” and observed student’s abilities (child is functionally illiterate) during reading tasks in the classroom.

Now, let’s move on to discuss the subjectivity of the weekly spelling test. A number of scientific studies on this subject have shown that spelling instruction needs to be direct, explicit and systematic in order to be effective for struggling learners. When teaching spelling, best instruction practices involve consistently addressing and grouping words according to specific spelling patterns rather than teaching random “grade level” or topically related words. However, in the vast majority of instances, the weekly spelling test continues to consist of random words which are expected to be memorized by students. As a result of these memorization practices, numerous students will attain high marks on spelling tests but will be absolutely unable to correctly spell these words in a variety of writing assignments even a week later.

Now, let’s move on to discuss the subjectivity of the weekly spelling test. A number of scientific studies on this subject have shown that spelling instruction needs to be direct, explicit and systematic in order to be effective for struggling learners. When teaching spelling, best instruction practices involve consistently addressing and grouping words according to specific spelling patterns rather than teaching random “grade level” or topically related words. However, in the vast majority of instances, the weekly spelling test continues to consist of random words which are expected to be memorized by students. As a result of these memorization practices, numerous students will attain high marks on spelling tests but will be absolutely unable to correctly spell these words in a variety of writing assignments even a week later.

The practice of teaching to the test is certainly not restricted to spelling. I have also seen similar practices pertaining to the subjects of science and social studies, whereas children are provided with specific handouts pertaining to a particular topic to memorize for the test. While this allows these children to perform well on such tests, unfortunately, their topic knowledge remains minimal to nonexistent given the fact that the memorized information will be long forgotten in a period of just a few weeks, if not sooner.

The practice of teaching to the test is certainly not restricted to spelling. I have also seen similar practices pertaining to the subjects of science and social studies, whereas children are provided with specific handouts pertaining to a particular topic to memorize for the test. While this allows these children to perform well on such tests, unfortunately, their topic knowledge remains minimal to nonexistent given the fact that the memorized information will be long forgotten in a period of just a few weeks, if not sooner.

Similarly, science projects and social studies book reports may not even be necessarily completed by the children themselves. Many parents of struggling learners will readily acknowledge the mammoth work they had contributed to such projects just so their children could attain good marks which were worth a significant percentage of the overall class grade.

Many parents of struggling learners will also readily admit their significant involvement in the homework process and how stressful and frustrating it is on the students. They report spending numerous hours each day explaining information, their children’s tears of frustration and rage, significant tantrum behavior, and in some extreme cases even visits to a hospital, subsequent to accidental injuries stemming from challenging behaviors.

Many parents of struggling learners will also readily admit their significant involvement in the homework process and how stressful and frustrating it is on the students. They report spending numerous hours each day explaining information, their children’s tears of frustration and rage, significant tantrum behavior, and in some extreme cases even visits to a hospital, subsequent to accidental injuries stemming from challenging behaviors.

Finally, the subjectivity of grading written assignments is another important factor that needs to be explicitly acknowledged. Many parents and professionals tasked with the evaluation of the students’ spontaneous written work will readily confirm that oftentimes the grades some struggling learners receive on written assignments appear to be almost ridiculously overinflated. Despite seemingly clear rubrics provided to the students explaining the breakdown of points for a particular written composition, many students end up receiving much higher marks than they deserve. I myself have observed this phenomenon firsthand by reviewing the written work of my clients in private practice following parental complaints of grade inflation.

We’re talking essays, blatantly lacking in coherence and cohesion, peppered with run-on and fragmented sentences, lacking subject-verb agreement, and full of grammatical errors, given A- and B+ grades, when the grading rubrics which came with the assignment, clearly indicate that the work is at the best deserving of a C- or a D+ grade.

We’re talking essays, blatantly lacking in coherence and cohesion, peppered with run-on and fragmented sentences, lacking subject-verb agreement, and full of grammatical errors, given A- and B+ grades, when the grading rubrics which came with the assignment, clearly indicate that the work is at the best deserving of a C- or a D+ grade.

These are just some of the many reasons why students of all ages with very noticeable language and learning needs, may end up being denied much-needed language and literacy assessments to determine the extent of their difficulties in order to receive targeted assistance.

Further complicating this issue is the fact that even when these students are finally tested in the school setting, due to the relative “mildness” of their deficits, coupled with the use of general (vs. targeted), often psychometrically weak tests, a lack of or under-identification of their deficit areas often occurs.

So what can parents and professionals do with this information? For starters, all are encouraged to examine the available information through a critical lens, albeit in different ways. Parents are encouraged to collect the samples of the child’s work (independent writing and spelling, audio samples of their reading, etc.) highlighting the discrepancies between the grades they receive and their actual abilities. They should absolutely request child study team assessments and if they are unsatisfied with the results of those tests they can seek out independent evaluations pertaining to the child’s areas of concern.

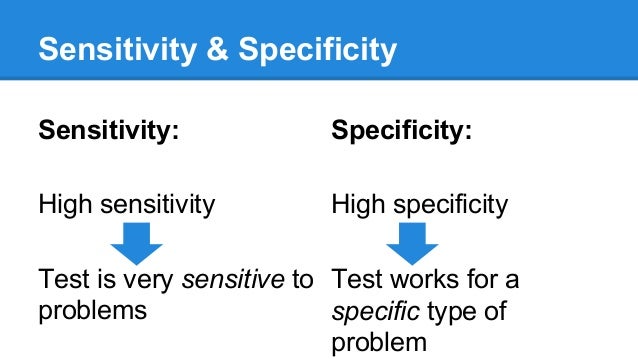

Similarly, SLPs are encouraged to review their testing practices to ensure that they accurately reflect the students’ deficit areas. They are also strongly encouraged to review the psychometric properties of the tests they are using to better understand the sensitivity and specificity of these instruments with respect to the appropriate identification of language disorders. Finally, SLPs are strongly encouraged to familiarize themselves with the language and literacy expectations of older students and utilize clinical assessment procedures which reflect more sensitive assessment practices.

Similarly, SLPs are encouraged to review their testing practices to ensure that they accurately reflect the students’ deficit areas. They are also strongly encouraged to review the psychometric properties of the tests they are using to better understand the sensitivity and specificity of these instruments with respect to the appropriate identification of language disorders. Finally, SLPs are strongly encouraged to familiarize themselves with the language and literacy expectations of older students and utilize clinical assessment procedures which reflect more sensitive assessment practices.

So the next time someone has concerns regarding the language and literacy abilities of students with seemingly good grades, do not be so hasty in dismissing their worries due to a “lack of academic impact”. Depending on the setting and testing in question, that impact may be far greater than you know!

Helpful Related Posts:

- Special Education Disputes and Comprehensive Language Testing: What Parents, Attorneys, and Advocates Need to Know

- What Makes an Independent Speech-Language-Literacy Evaluation a GOOD Evaluation?

- What Research Shows About the Functional Relevance of Standardized Language Tests

- Part II: Components of Comprehensive Dyslexia Testing – Phonological Awareness and Word Fluency Assessment

- On the Limitations of Using Vocabulary Tests with School-Aged Students

- It’s All Due to …Language: How Subtle Symptoms Can Cause Serious Academic Deficits

- Dear Reading Specialist, May I Ask You a Few Questions?

- Help, My Student has a Huge Score Discrepancy Between Tests and I Don’t Know Why?

- The Reign of the Problematic PLS-5 and the Rise of the Hyperintelligent Potato

- Components of Qualitative Writing Assessments: What Exactly are We Trying to Measure?

Very true! In my district we always talk about “educational impact” and are quick to think there is no adverse impact when there really might be. Great post!

[…] Lately, I’ve been seeing more and more posts on social media asking for testing suggestions for students who exhibit subtle language-based difficulties. Many of these children are typically referred for initial assessments or reassessments as part of advocate/attorney involved cases, while others are being assessed due to the parental insistence that something “is not quite right” with their language and literacy abilities, even in the presence of “good grades.” […]