Speech Language Assessment Checklist Sample for Adolescents

Information Collection, Use, and Sharing

We are the sole owners of the information collected on this site. We only have access to/collect information that you voluntarily give us via email or another direct contact from you. We will not sell or rent this information to anyone.

We will use your information to respond to you, regarding the reason you contacted us. We will not share your information with any third party outside of our organization, other than as necessary to fulfill your request, e.g. to ship an order.

Unless you ask us not to, we may contact you via email in the future to tell you about specials, new products or services, or changes to this privacy policy.

Your Access to and Control Over Information

You may opt out of any future contacts from us at any time. You can do the following at any time by contacting us via the email address or phone number given on our website:

Security

We take precautions to protect your information. When you submit sensitive information via the website, your information is protected both online and offline.

Wherever we collect sensitive information, that information is encrypted and transmitted to us in a secure way. You can verify this by looking for a lock icon in the address bar and looking for “https” at the beginning of the address of the Web page.

While we use encryption to protect sensitive information transmitted online, we also protect your information offline. Only employees who need the information to perform a specific job (for example, billing or customer service) are granted access to personally identifiable information. The computers/servers in which we store personally identifiable information are kept in a secure environment.

Cookies

We use “cookies” on this site. A cookie is a piece of data stored on a site visitor’s hard drive to help us improve your access to our site and identify repeat visitors to our site. For instance, when we use a cookie to identify you, you would not have to log in a password more than once, thereby saving time while on our site. Cookies can also enable us to track and target the interests of our users to enhance the experience on our site. Usage of a cookie is in no way linked to any personally identifiable information on our site.

If you feel that we are not abiding by this privacy policy, you should contact us immediately via our Contact Form

When many of us think of such labels as “language disorder” or “learning disability”, very infrequently do adolescents (students 13-18 years of age) come to mind. Even today, much of the research in the field of pediatric speech pathology involves preschool and school-aged children under 12 years of age.

When many of us think of such labels as “language disorder” or “learning disability”, very infrequently do adolescents (students 13-18 years of age) come to mind. Even today, much of the research in the field of pediatric speech pathology involves preschool and school-aged children under 12 years of age.

The prevalence and incidence of language disorders in adolescents is very difficult to estimate due to which some authors even referred to them as a Neglected Group with Significant Problems having an “invisible disability“.

Far fewer speech language therapists work with middle-schoolers vs. preschoolers and elementary aged kids, while the numbers of SLPs working with high-school aged students is frequently in single digits in some districts while being completely absent in others. In fact, I am frequently told (and often see it firsthand) that some administrators try to cut costs by attempting to dictate a discontinuation of speech-language services on the grounds that adolescents “are far too old for services” or can “no longer benefit from services”.

But of course the above is blatantly false. Undetected language deficits don’t resolve with age! They simply exacerbate and turn into learning disabilities. Similarly, lack of necessary and appropriate service provision to children with diagnosed language impairments at the middle-school and high-school levels will strongly affect their academic functioning and hinder their future vocational outcomes.

A cursory look at the Speech Pathology Related Facebook Groups as well as ASHA forums reveals numerous SLPs in a continual search for best methods of assessment and treatment of older students (~12-18 years of age).

Consequently, today I wanted to dedicate this post to a review of standardized assessments options available for students 12-18 years of age with suspected language and literacy deficits.

Most comprehensive standardized assessments, “typically focus on semantics, syntax, morphology, and phonology, as these are the performance areas in which specific skill development can be most objectively measured” (Hill & Coufal, 2005, p 35). Very few of them actually incorporate aspects of literacy into its subtests in a meaningful way. Yet by the time students reach adolescence literacy begins to play an incredibly critical role not just in all the aspects of academics but also social communication.

So when it comes to comprehensive general language testing I highly recommended that SLPs select standardized measures with a focus on not language but also literacy. Presently of all the comprehensive assessment tools I highly prefer the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS) for students up to 18 years of age, (see a comprehensive review HERE), which covers such literacy areas as phonological awareness, reading fluency, reading comprehension, writing and spelling in addition to traditional language areas as as vocabulary awareness, following directions, story recall, etc. However, while comprehensive tests have numerous uses, their sole administration will not constitute an adequate assessment.

So what areas should be assessed during language and literacy testing? Below are a few suggestions of standardized testing measures (and informal procedures) aimed at exploring the student abilities in particular areas pertaining to language and literacy.

TESTS OF LANGUAGE

It is understandable how given the sheer amount of assessment choices some clinicians may feel overwhelmed and be unsure regarding the starting point of an adolescent evaluation. Consequently, the use the checklist prior to the initiation of assessment may be highly useful in order to identify potential language weaknesses/deficits the students might experience. It will also allow clinicians to prioritize the hierarchy of testing instruments to use during the assessment.

While clinicians are encouraged to develop such checklists for their personal use, those who lack time and opportunity can locate a number of already available checklists on the market.

For example, the comprehensive 6-page Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents (below) can be given to caregivers, classroom teachers, and even older students in order to check off the most pressing difficulties the student is experiencing in an academic setting.

It is important for several individuals to fill out this checklist to ensure consistency of deficits, prior to determining whether an assessment is warranted in the first place and if so, which assessment areas need to be targeted.

Checklist Categories:

Based on the checklist administration SLPs can reliably pinpoint the student’s areas of deficits without needless administration of unrelated/unnecessary testing instruments. For example, if a student presents with deficits in the areas of problem solving and social pragmatic functioning the administration of a general language test such as the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals® – Fifth Edition (CELF-5) would NOT be functional (especially if the previous administration of educational testing did not reveal any red flags). In contrast, the administration of such tests as Test Of Problem Solving 2 Adolescent and Social Language Development Test Adolescent would be better reflective of the student’s deficits in the above areas. (Checklist HERE; checklist sample HERE).

It is very important to understand that students presenting with language and literacy deficits will not outgrow these deficits on their own. While there may be “a time period when the students with early language disorders seem to catch up with their typically developing peers” (e.g., illusory recovery) by undergoing a “spurt” in language learning”(Sun & Wallach, 2014). These spurts are typically followed by a “post-spurt plateau”. This is because due to the ongoing challenges and an increase in academic demands “many children with early language disorders fail to “outgrow” these difficulties or catch up with their typically developing peers”(Sun & Wallach, 2014). As such many adolescents “may not show academic or language-related learning difficulties until linguistic and cognitive demands of the task increase and exceed their limited abilities” (Sun & Wallach, 2014). Consequently, SLPs must consider the “underlying deficits that may be masked by early oral language development” and “evaluate a child’s language abilities in all modalities, including pre-literacy, literacy, and metalinguistic skills” (Sun & Wallach, 2014).

References:

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Resources

Recently, I’ve participated in various on-line and in-person discussions with both school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) as well as medical health professionals (e.g., neurologists, pediatricians, etc.) regarding their views on the need of formal diagnosis for school aged children with suspected alcohol related deficits. While their responses differed considerably from: “we do not base intervention on diagnosis, but rather on demonstrated student need” to “with a diagnosis of ASD ‘these children’ would get the same level of services“, the message I was receiving loud and clear was: “Why? What would be the point?” So today I decided to share my views on this matter and explain why I think the diagnosis matters.

Recently, I’ve participated in various on-line and in-person discussions with both school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) as well as medical health professionals (e.g., neurologists, pediatricians, etc.) regarding their views on the need of formal diagnosis for school aged children with suspected alcohol related deficits. While their responses differed considerably from: “we do not base intervention on diagnosis, but rather on demonstrated student need” to “with a diagnosis of ASD ‘these children’ would get the same level of services“, the message I was receiving loud and clear was: “Why? What would be the point?” So today I decided to share my views on this matter and explain why I think the diagnosis matters.

Continue reading Why is FASD diagnosis so important?

Smart Speech Therapy (SST) LLC Receives ASHA Approved Continuing Education (CE) Provider Recognition

ASHA Approved CE Provider Status Demonstrates Commitment to High-Quality CE Programming for Audiologists and Speech-Language Pathologists Continue reading Smart Speech Therapy LLC Receives ASHA Approved Continuing Education (CE) Provider Recognition

Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?”

Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?”

Of course, the answer is never that simple. Just because a child has a diagnosis of a social communication disorder, word-finding deficits, or a reading disability does not automatically indicate to the treating clinician, which ‘cookie cutter’ materials and programs are best suited for the child in question. Only a profile of strengths and needs based on a comprehensive language and literacy testing can address this in an adequate and targeted manner.

To illustrate, reading intervention is a much debated and controversial topic nowadays. Everywhere you turn there’s a barrage of advice for clinicians and parents regarding which program/approach to use. Barton, Wilson, OG… the well-intentioned advice just keeps on coming. The problem is that without knowing the child’s specific deficit areas, the application of the above approaches is quite frankly … pointless.

There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader?

There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader?

Let’s a take a look at an example, below. It’s the CTOPP-2 results of a 7-6-year-old female with a documented history of extensive reading difficulties and a significant family history of reading disabilities in the family.

Results of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing-2 (CTOPP-2)

| Subtests | Scaled Scores | Percentile Ranks | Description |

| Elision (EL) | 7 | 16 | Below Average |

| Blending Words (BW) | 13 | 84 | Above Average |

| Phoneme Isolation (PI) | 6 | 9 | Below Average |

| Memory for Digits (MD) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Nonword Repetition (NR) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Rapid Digit Naming (RD) | 10 | 50 | Average |

| Rapid Letter Naming (RL) | 11 | 63 | Average |

| Blending Nonwords (BN) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Segmenting Nonwords (SN) | 8 | 25 | Average |

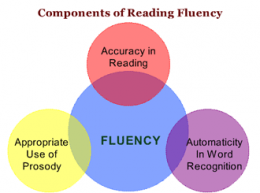

However, the results of her CTOPP-2 testing clearly indicate that phonological awareness, despite two areas of mild weaknesses, is not really a significant problem for this child. So let’s look at the student’s reading fluency results.

Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

So now we know that despite quite decent phonological awareness abilities, this student presents with quite poor sound-letter correspondence skills and will definitely benefit from explicit phonics instruction addressing the above deficit areas. But that is only the beginning! By looking at the analysis of specific misreadings we next need to determine what other literacy areas need to be addressed. For the sake of brevity, I can specify that further analysis of this child reading abilities revealed that reading comprehension, orthographic knowledge, as well as morphological awareness were definitely areas that also required targeted remediation. The assessment also revealed that the child presented with poor spelling and writing abilities, which also needed to be addressed in the context of therapy.

Now, what if I also told you that this child had already been receiving private, Orton-Gillingham reading instruction for a period of 2 years, 1x per week, at the time the above assessment took place? Would you change your mind about the program in question?

Well, the answer is again not so simple! OG is a fine program, but as you can see from the above example it has definite limitations and is not an exclusive fit for this child, or for any child for that matter. Furthermore, a solidly-trained in literacy clinician DOES NOT need to rely on just one program to address literacy deficits. They simply need solid knowledge of typical and atypical language and literacy development/milestones and know how to create a targeted treatment hierarchy in order to deliver effective intervention services. But for that, they need to first, thoughtfully, construct assessment-based treatment goals by carefully taking into the consideration the child’s strengths and needs.

So let’s stop asking which approach/program we should use and start asking about the child’s profile of strengths and needs in order to create accurate language and literacy goals based on solid evidence and scientifically-guided treatment practices.

Helpful Resources Pertaining to Reading:

Today I am very excited to introduce my new product “Pediatric Background History Questionnaire”. I’ve been blogging quite a bit lately on the topic of obtaining a thorough developmental client history in order to make an appropriate and accurate diagnosis of the child’s difficulties for relevant classroom placement, appropriate accommodations and modifications as well as targeted and relevant therapeutic services.

Today I am very excited to introduce my new product “Pediatric Background History Questionnaire”. I’ve been blogging quite a bit lately on the topic of obtaining a thorough developmental client history in order to make an appropriate and accurate diagnosis of the child’s difficulties for relevant classroom placement, appropriate accommodations and modifications as well as targeted and relevant therapeutic services.

Continue reading Pediatric Background History Questionnaire Giveaway

Recently, I’ve published an article in SIG 16 Perspectives on School Based Issues discussing the importance of social communication assessments of school aged children 2-18 years of age. Below I would like to summarize article highlights.

Recently, I’ve published an article in SIG 16 Perspectives on School Based Issues discussing the importance of social communication assessments of school aged children 2-18 years of age. Below I would like to summarize article highlights.

First, I summarize the effect of social communication on academic abilities and review the notion of the “academic impact”. Then, I go over important changes in terminology and definitions as well as explain the “anatomy of social communication”.

Next I suggest a sample social communication skill hierarchy to adequately determine assessment needs (assess only those abilities suspected of deficits and exclude the skills the student has already mastered).

After that I go over pre-assessment considerations as well as review standardized testing and its limitations from 3-18 years of age.

Finally I review a host of informal social communication procedures and address their utility.

What is the away message?

When evaluating social communication, clinicians need to use multiple assessment tasks to create a balanced assessment. We need to chose testing instruments that will help us formulate clear goals. We also need to add descriptive portions to our reports in order to “personalize” the student’s deficit areas. Our assessments need to be functional and meaningful for the student. This means determining the student’s strengths and not just weaknesses as a starting point of intervention initiation.

Is this an article which you might find interesting? If so, you can access full article HERE free of charge.

Helpful Smart Speech Resources Related to Assessment and Treatment of Social Communication