Improving Social Communication Abilities in Children with Psychiatric Impairments

One common difficulty our “higher functioning” (refers to subjective notion of ‘perceived’ functioning in school setting only) language impaired students with social communication and executive function difficulties present with – is lack of insight into own strengths and weaknesses.

One common difficulty our “higher functioning” (refers to subjective notion of ‘perceived’ functioning in school setting only) language impaired students with social communication and executive function difficulties present with – is lack of insight into own strengths and weaknesses.

Yet insight is a very important skill, which most typically developing students exhibit without consciously thinking about it. Having insight allows students to review work for errors, compensate for any perceived weaknesses effectively, and succeed with efficient juggling of academic workload.

In contrast, lack of insight in students with language deficits further compounds their difficulties, as they lack realization into own weaknesses and as a result are unable to effectively compensate for them.

That is why I started to explicitly teach the students on my caseload in both psychiatric hospital and private practice the concept of insight.

Now some of you may have some legitimate concerns. You may ask: “How can one teach such an abstract concept to students who are already impaired in their comprehension of language?” The answer to that is – I teach this concept through a series of concrete steps as well as through the introduction of abstract definitions, simplified for the purpose of my sessions into concrete terms.

Furthermore, it is important to understand that the acquisition of “insight” cannot be accomplished in one or even several sessions. Rather after this concept is introduced and the related vocabulary has been ‘internalized’ by the student, thematic therapy sessions can be used to continue the acquisition of “insight” for months and even years to come.

How do we begin?

When I first started teaching this concept I used to explain the terminology related to “insight” verbally to students. However, as my own ‘insight’ developed in response to the students’ performance, I created a product to assist them with the acquisition of insight (See HERE).

Intended Audiences:

This thematic 10 page packet targets the development of “insight” in students with average IQ, 8+ years of age, presenting with social pragmatic and executive function difficulties.

The packet contains 1 page text explaining the concept of insight to students.

It also contains 11 Tier II vocabulary words relevant to the discussion of insight and their simplified definitions. The words were selected based on course curriculum standards for several grade levels (fourth through seventh) due to their wide usage in a variety of subjects (social studies, science, math, etc.)

Language activities in this packet include:

And now a few words regarding the lesson structure…

I introduce the concept of “insight” to clients by writing down the word and asking them to identify its parts: ‘in‘ and ‘sight‘. Depending on the student’s level of abilities I either get to the students to explain it to me or explain it myself that it is a compound word made up of two other words.

I then ask the students to interpret what the word could potentially mean. After I hear their responses I either confirm the correct one or end up explaining that this word refers to “looking into one’s brain” for answers related to how well someone understands information.

I have the students read the text located on the first page of my packet going over the concept of insight and some of its associated vocabulary words. I ask the students to tell me the main idea of each paragraph as well as answer questions regarding supporting text details.

Once I am confident that the students have a fairly good grasp of the presented text I move on to the definitions page. There are actually two definition pages in the lesson: one at the beginning and one at the end of the packet. The first definitions page also contains word meaning and what parts of speech the definitions belong to. The definition page at the end of the packet contains only the targeted words. It is now the students responsibility to write down the definition of all the vocabulary words and phrases in order for me to see how well they remember the meanings of pertinent words.

The packet also includes comprehension questions, a section on sentence construction several morphological awareness activities, a crossword puzzle and a self-reflection page.

The final activity in the packet requires the student to judge their own work performance during this activity. I ask students questions such as:

If a student responds “I know I did well because I understood everything”, I typically ask them to prove their comprehension to me, verbally. Here the goal is to have the student provide concrete verbal examples supporting their insight of their performance.

This may include statements such as:

As mentioned above this activity is only the beginning. After I ensure that the students have a decent grasp of this concept I continue working on it indirectly by having the students continuously judge their own performance on a variety of other therapy related activities and assignments.

You can find the complete packet on teaching “insight” in my online store (HERE). Also, stay tuned for Part II of this series, which will describe how to continue solidifying the concept of “insight” in the context of therapy sessions for students with social pragmatic and executive function deficits.

Helpful Smart Speech Resources:

I have been using Social Language Development Tests (SLDT) from Linguisystems since they were first published a number of years ago and I like them a great deal. For those of you unfamiliar with them – there are two versions of SLDT, elementary (for children 6-12 years of age) and adolescent (for children 12-18 years of age). These are tests of social language competence, which assess such skills as taking on first person perspective, making correct inferences, negotiating conflicts with peers, being flexible in interpreting situations and supporting friends diplomatically (SLDT-E). Continue reading Spotlight on Social Language Competence: When is a high subtest score a cause for concern?

I have been using Social Language Development Tests (SLDT) from Linguisystems since they were first published a number of years ago and I like them a great deal. For those of you unfamiliar with them – there are two versions of SLDT, elementary (for children 6-12 years of age) and adolescent (for children 12-18 years of age). These are tests of social language competence, which assess such skills as taking on first person perspective, making correct inferences, negotiating conflicts with peers, being flexible in interpreting situations and supporting friends diplomatically (SLDT-E). Continue reading Spotlight on Social Language Competence: When is a high subtest score a cause for concern?

Scenario: Len is a 7-2-year-old, 2nd-grade student who struggles with reading and writing in the classroom. He is very bright and has a high average IQ, yet when he is speaking he frequently can’t get his point across to others due to excessive linguistic reformulations and word-finding difficulties. The problem is that Len passed all the typical educational and language testing with flying colors, receiving average scores across the board on various tests including the Woodcock-Johnson Fourth Edition (WJ-IV) and the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 (CELF-5). Stranger still is the fact that he aced Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Second Edition (CTOPP-2), with flying colors, so he is not even eligible for a “dyslexia” diagnosis. Len is clearly struggling in the classroom with coherently expressing self, telling stories, understanding what he is reading, as well as putting his thoughts on paper. His parents have compiled impressively huge folders containing examples of his struggles. Yet because of his performance on the basic standardized assessment batteries, Len does not qualify for any functional assistance in the school setting, despite being virtually functionally illiterate in second grade.

Scenario: Len is a 7-2-year-old, 2nd-grade student who struggles with reading and writing in the classroom. He is very bright and has a high average IQ, yet when he is speaking he frequently can’t get his point across to others due to excessive linguistic reformulations and word-finding difficulties. The problem is that Len passed all the typical educational and language testing with flying colors, receiving average scores across the board on various tests including the Woodcock-Johnson Fourth Edition (WJ-IV) and the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 (CELF-5). Stranger still is the fact that he aced Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Second Edition (CTOPP-2), with flying colors, so he is not even eligible for a “dyslexia” diagnosis. Len is clearly struggling in the classroom with coherently expressing self, telling stories, understanding what he is reading, as well as putting his thoughts on paper. His parents have compiled impressively huge folders containing examples of his struggles. Yet because of his performance on the basic standardized assessment batteries, Len does not qualify for any functional assistance in the school setting, despite being virtually functionally illiterate in second grade.

The truth is that Len is quite a familiar figure to many SLPs, who at one time or another have encountered such a student and asked for guidance regarding the appropriate accommodations and services for him on various SLP-geared social media forums. But what makes Len such an enigma, one may inquire? Surely if the child had tangible deficits, wouldn’t standardized testing at least partially reveal them?

Well, it all depends really, on what type of testing was administered to Len in the first place. A few years ago I wrote a post entitled: “What Research Shows About the Functional Relevance of Standardized Language Tests“. What researchers found is that there is a “lack of a correlation between frequency of test use and test accuracy, measured both in terms of sensitivity/specificity and mean difference scores” (Betz et al, 2012, 141). Furthermore, they also found that the most frequently used tests were the comprehensive assessments including the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals and the Preschool Language Scale as well as one-word vocabulary tests such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test”. Most damaging finding was the fact that: “frequently SLPs did not follow up the comprehensive standardized testing with domain-specific assessments (critical thinking, social communication, etc.) but instead used the vocabulary testing as a second measure”.(Betz et al, 2012, 140)

In other words, many SLPs only use the tests at hand rather than the RIGHT tests aimed at identifying the student’s specific deficits. But the problem doesn’t actually stop there. Due to the variation in psychometric properties of various tests, many children with language impairment are overlooked by standardized tests by receiving scores within the average range or not receiving low enough scores to qualify for services.

Thus, “the clinical consequence is that a child who truly has a language impairment has a roughly equal chance of being correctly or incorrectly identified, depending on the test that he or she is given.” Furthermore, “even if a child is diagnosed accurately as language impaired at one point in time, future diagnoses may lead to the false perception that the child has recovered, depending on the test(s) that he or she has been given (Spaulding, Plante & Farinella, 2006, 69).”

There’s of course yet another factor affecting our hypothetical client and that is his relatively young age. This is especially evident with many educational and language testing for children in the 5-7 age group. Because the bar is set so low, concept-wise for these age-groups, many children with moderate language and literacy deficits can pass these tests with flying colors, only to be flagged by them literally two years later and be identified with deficits, far too late in the game. Coupled with the fact that many SLPs do not utilize non-standardized measures to supplement their assessments, Len is in a pretty serious predicament.

But what if there was a do-over? What could we do differently for Len to rectify this situation? For starters, we need to pay careful attention to his deficits profile in order to choose appropriate tests to evaluate his areas of needs. The above can be accomplished via a number of ways. The SLP can interview Len’s teacher and his caregiver/s in order to obtain a summary of his pressing deficits. Depending on the extent of the reported deficits the SLP can also provide them with a referral checklist to mark off the most significant areas of need.

In Len’s case, we already have a pretty good idea regarding what’s going on. We know that he passed basic language and educational testing, so in the words of Dr. Geraldine Wallach, we need to keep “peeling the onion” via the administration of more sensitive tests to tap into Len’s reported areas of deficits which include: word-retrieval, narrative production, as well as reading and writing.

For that purpose, Len is a good candidate for the administration of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS), which was developed to identify language and literacy disorders, has good psychometric properties, and contains subtests for assessment of relevant skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school-age children.

For that purpose, Len is a good candidate for the administration of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS), which was developed to identify language and literacy disorders, has good psychometric properties, and contains subtests for assessment of relevant skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school-age children.

Given Len’s reported history of narrative production deficits, Len is also a good candidate for the administration of the Social Language Development Test Elementary (SLDTE). Here’s why. Research indicates that narrative weaknesses significantly correlate with social communication deficits (Norbury, Gemmell & Paul, 2014). As such, it’s not just children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who present with impaired narrative abilities. Many children with developmental language impairment (DLD) (#devlangdis) can present with significant narrative deficits affecting their social and academic functioning, which means that their social communication abilities need to be tested to confirm/rule out presence of these difficulties.

Given Len’s reported history of narrative production deficits, Len is also a good candidate for the administration of the Social Language Development Test Elementary (SLDTE). Here’s why. Research indicates that narrative weaknesses significantly correlate with social communication deficits (Norbury, Gemmell & Paul, 2014). As such, it’s not just children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who present with impaired narrative abilities. Many children with developmental language impairment (DLD) (#devlangdis) can present with significant narrative deficits affecting their social and academic functioning, which means that their social communication abilities need to be tested to confirm/rule out presence of these difficulties.

However, standardized tests are not enough, since even the best-standardized tests have significant limitations. As such, several non-standardized assessments in the areas of narrative production, reading, and writing, may be recommended for Len to meaningfully supplement his testing.

Let’s begin with an informal narrative assessment which provides detailed information regarding microstructural and macrostructural aspects of storytelling as well as child’s thought processes and socio-emotional functioning. My nonstandardized narrative assessments are based on the book elicitation recommendations from the SALT website. For 2nd graders, I use the book by Helen Lester entitled Pookins Gets Her Way. I first read the story to the child, then cover up the words and ask the child to retell the story based on pictures. I read the story first because: “the model narrative presents the events, plot structure, and words that the narrator is to retell, which allows more reliable scoring than a generated story that can go in many directions” (Allen et al, 2012, p. 207).

As the child is retelling his story I digitally record him using the Voice Memos application on my iPhone, for a later transcription and thorough analysis. During storytelling, I only use the prompts: ‘What else can you tell me?’ and ‘Can you tell me more?’ to elicit additional information. I try not to prompt the child excessively since I am interested in cataloging all of his narrative-based deficits. After I transcribe the sample, I analyze it and make sure that I include the transcription and a detailed write-up in the body of my report, so parents and professionals can see and understand the nature of the child’s errors/weaknesses.

Now we are ready to move on to a brief nonstandardized reading assessment. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Reading for Comprehension, which contains books for grades 1-8. After I confirm with either the parent or the child’s teacher that the selected passage is reflective of the complexity of work presented in the classroom for his grade level, I ask the child to read the text. As the child is reading, I calculate the correct number of words he reads per minute as well as what type of errors the child is exhibiting during reading. Then I ask the child to state the main idea of the text, summarize its key points as well as define select text embedded vocabulary words and answer a few, verbally presented reading comprehension questions. After that, I provide the child with accompanying 5 multiple choice question worksheet and ask the child to complete it. I analyze my results in order to determine whether I have accurately captured the child’s reading profile.

Now we are ready to move on to a brief nonstandardized reading assessment. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Reading for Comprehension, which contains books for grades 1-8. After I confirm with either the parent or the child’s teacher that the selected passage is reflective of the complexity of work presented in the classroom for his grade level, I ask the child to read the text. As the child is reading, I calculate the correct number of words he reads per minute as well as what type of errors the child is exhibiting during reading. Then I ask the child to state the main idea of the text, summarize its key points as well as define select text embedded vocabulary words and answer a few, verbally presented reading comprehension questions. After that, I provide the child with accompanying 5 multiple choice question worksheet and ask the child to complete it. I analyze my results in order to determine whether I have accurately captured the child’s reading profile.

Finally, if any additional information is needed, I administer a nonstandardized writing assessment, which I base on the Common Core State Standards for 2nd grade. For this task, I provide a student with a writing prompt common for second grade and give him a period of 15-20 minutes to generate a writing sample. I then analyze the writing sample with respect to contextual conventions (punctuation, capitalization, grammar, and syntax) as well as story composition (overall coherence and cohesion of the written sample).

The above relatively short assessment battery (2 standardized tests and 3 informal assessment tasks) which takes approximately 2-2.5 hours to administer, allows me to create a comprehensive profile of the child’s language and literacy strengths and needs. It also allows me to generate targeted goals in order to begin effective and meaningful remediation of the child’s deficits.

Children like Len will, unfortunately, remain unidentified unless they are administered more sensitive tasks to better understand their subtle pattern of deficits. Consequently, to ensure that they do not fall through the cracks of our educational system due to misguided overreliance on a limited number of standardized assessments, it is very important that professionals select the right assessments, rather than the assessments at hand, in order to accurately determine the child’s areas of needs.

References:

Social media forums have long been subject to a variety of criticism related to trustworthiness, reliability, and commercialization of content. However, in recent years the spread of misinformation has been steadily increasing in disproportionate amounts as compared to the objective consumption of evidence. Facebook, for example, has long been criticized, for the ease with which its members can actively promote and rampantly encourage the spread of misinformation on its platform.

To illustrate, one study found that “from August 2020 to January 2021, misinformation got six times more clicks on Facebook than posts containing factual news. Misinformation also accounted for the vast majority of engagement with far-right posts — 68% — compared to 36% of posts coming from the far-left.” Facebook has even admitted in the past that its platform is actually hardwired for misinformation. Nowhere is it easier to spread misinformation than in Facebook groups. In contrast to someone’s personal account, a dubious claim made even in a relatively small group has a far wider audience than a claim made from one’s personal account. In the words of Nina Jankowicz, the disinformation fellow at the Wilson Center, “Facebook groups are ripe targets for bad actors, for people who want to spread misleading, wrong or dangerous information. “

Continue reading In Search of Evidence in the Era of Social Media Misinformation Several years after I started my private speech pathology practice, I began performing comprehensive independent speech and language evaluations (IEEs).

Several years after I started my private speech pathology practice, I began performing comprehensive independent speech and language evaluations (IEEs).

For those of you who may be hearing the term IEE for the first time, an Independent Educational Evaluation is “an evaluation conducted by a qualified examiner who is not employed by the public agency responsible for the education of the child in question.” 34 C.F.R. 300.503. IEE’s can evaluate a broad range of functioning outside of cognitive or academic performance and may include neurological, occupational, speech language, or any other type of evaluations as long as they bear direct impact on the child’s educational performance.

Independent evaluations can be performed for a wide variety of reasons, including but not limited to:

Why can’t similar assessments be performed in school settings?

There are several reasons for that.

Why are IEE’s Needed?

The answer to that is simple: “To strengthen the role of parents in the educational decision-making process.” According to one Disability Rights site: “Many disagreements between parents and school staff concerning IEP services and placement involve, at some stage, the interpretation of evaluation findings and recommendations. When disagreements occur, the Independent Educational Evaluation (IEE) is one option lawmakers make available to parents, to help answer questions about appropriate special education services and placement“.

Indeed, many of the clients who retain my services also retain the services of educational advocates as well as special education lawyers. Many of them work on determining appropriate level of services as well as an out of district placement for the children with a variety of special education needs. However, one interesting reoccurring phenomenon I’ve noted over the years is that only a small percentage of special education lawyers, educational advocates, and even parents believed that children with autism spectrum disorders, genetic syndromes, social pragmatic deficits, emotional disturbances, or reading disabilities required a comprehensive language evaluation/reevaluation prior to determining an appropriate out of district placement or an in-district change of service provision.

So today I would like to make a case, in favor of comprehensive independent language evaluations being a routine component of every special education dispute involving a child with impaired academic performance. I will do so through the illustration of past case scenarios that clearly show that comprehensive independent language evaluations do matter, even when it doesn’t look like they may be needed.

Case A: “He is just a weak student”.

Several years ago I was contacted by a parent of a 12 year old boy, who was concerned with his son’s continuously failing academic performance. The child had not qualified for an IEP but was receiving 504 plan in school setting and was reported to significantly struggle due to continuous increase of academic demands with each passing school year. An in-district language evaluation had been preformed several years prior. It showed that the student’s general language abilities were in the low average range of functioning due to which he did not qualify for speech language services in school setting. However, based on the review of available records it very quickly became apparent that many of the academic areas in which the student struggled (e.g., reading comprehension, social pragmatic ability, critical thinking skills, etc) were simply not assessed by the general language testing. I had suggested to the parent a comprehensive language evaluation and explained to him on what grounds I was recommending this course of action. That comprehensive 4 hour assessment broken into several testing sessions revealed that the student presented with severe receptive, expressive, problem solving and social pragmatic language deficits, as well as moderate executive function deficits, which required therapeutic intervention.

Prior to that assessment the parent, reinforced by the feedback from his child’s educational staff believed his son to be an unmotivated student who failed to apply himself in school setting. However, after the completion of that assessment, the parent clearly understood that it wasn’t his child’s lack of motivation which was impeding his academic performance but rather a true learning disability was making it very difficult for his son to learn without the necessary related services and support. Several months after the appropriate related services were made available to the child in school setting on the basis of the performed IEE, the parent reported significant progress in his child academic performance.

Case B: “She’s just not learning because of her behavior, so there’s nothing we can do”.

This case involved a six year old girl who presented with a severe speech – language disorder and behavioral deficits in school setting secondary to an intellectual disability of an unspecified origin.

In contrast to Case A scenario, this child had received a variety of assessments and therapies since a very early age; however, her parents were becoming significantly concerned regarding her regression of academic functioning in school setting and felt that a more specialized out of district program with a focus on multiple disabilities would be better suitable to her needs. Unfortunately the school disagreed with them and believed that she could be successfully educated in an in-district setting (despite evidence to the contrary). Interestingly, an in-depth comprehensive speech language assessment had never been performed on this child because her functioning was considered to be “too low” for such an assessment.

Comprehensive assessment of this little girl’s abilities revealed that via an application of a variety of behavioral management techniques (of non-ABA origin), and highly structured language input, she was indeed capable of significantly better performance then she had exhibited in school setting. It stood to reason that if she were placed in a specialized school setting composed of educational professionals who were trained in dealing with her complex behavioral and communication needs, her performance would continue to steadily improve. Indeed, six months following a transfer in schools her parents reported a “drastic” change pertaining to a significant reduction in challenging behavioral manifestations as well as significant increase in her linguistic output.

Case C: “Your child can only learn so much because of his genetic syndrome”.

This case scenario does not technically involve just one child but rather three different male students between 9 and 11 years of age with several ‘common’ genetic syndromes: Down, Fragile X, and Klinefelter. All three were different ages, came from completely different school districts, and were seen by me in different calendar years.

However, all three boys had one thing in common, because of their genetic syndromes, which were marked by varying degrees of intellectual disability as well as speech language weaknesses, their parents were collectively told that there could be very little done for them with regards to expanding their expressive language as well as literacy development.

Similarly to the above scenarios, none of the children had undergone comprehensive language testing to determine their strengths, weaknesses, and learning styles. Comprehensive assessment of each student revealed that each had the potential to improve their expressive abilities to speak in compound and complex sentences. Dynamic assessment of literacy also revealed that it was possible to teach each of them how to read.

Following the respective assessments, some of these students had became my private clients, while others’s parents have periodically written to me, detailing their children’s successes over the years. Each parent had conveyed to me how “life-changing”a comprehensive IEE was to their child.

Case D: “Their behavior is just out of control”

The final case scenario I would like to discuss today involves several students with an educational classification of “Emotionally Disturbed” (pg 71). Those of you who are familiar with my blog and my work know that my main area of specialty is working with school age students with psychiatric impairments and emotional behavioral disturbances. There are a number of reasons why I work with this challenging pediatric population. One very important reason is that these students continue to be grossly underserved in school setting. Over the years I have written a variety of articles and blog posts citing a number of research studies, which found that a significant number of students with psychiatric impairments and emotional behavioral disturbances present with undiagnosed linguistic impairments (especially in the area of social communication), which adversely impact their school-based performance.

Here, we are not talking about two or three students rather we’re talking about the numbers in the double digits of students with psychiatric impairments and emotional disturbances, who did not receive appropriate therapies in their respective school settings.

The majority of these students were divided into two distinct categories. In the first category, students began to manifest moderate-to-severe speech language deficits from a very early age. They were classified in preschool and began receiving speech language therapy. However by early elementary age their general language abilities were found to be within the average range of functioning and their language therapies were discontinued. Unfortunately since general language testing does not assess all categories of linguistic functioning such as critical thinking, executive functions, social communication etc., these students continued to present with hidden linguistic impairments, which continued to adversely impact their behavior.

Students in the second category also began displaying emotional and behavioral challenges from a very early age. However, in contrast to the students in the first category the initial language testing found their general language abilities to be within the average range of functioning. As a result these students never received any language-based therapies and similar to the students in the first category, their hidden linguistic impairments continued to adversely impact their behavior.

Students in both categories ended up following a very similar pattern of behavior. Their behavioral challenges in the school continued to escalate. These were followed by a series of suspensions, out of district placements, myriad of psychiatric and neuropsychological evaluations, until many were placed on home instruction. The one vital element missing from all of these students’ case records were comprehensive language evaluations with an emphasis on assessing their critical thinking, executive functions and social communication abilities. Their worsening patterns of functioning were viewed as “severe misbehaving” without anyone suspecting that their hidden language deficits were a huge contributing factor to their maladaptive behaviors in school setting.

Conclusion:

So there you have it! As promised, I’ve used four vastly different scenarios that show you the importance of comprehensive language evaluations in situations where it was not so readily apparent that they were needed. I hope that parents and professionals alike will find this post helpful in reconsidering the need for comprehensive independent evaluations for students presenting with impaired academic performance.

In recent years there has been a substantial rise in awareness pertaining to reading disorders in young school-aged children. Consequently, more and more parents and professionals are asking questions regarding how early can “dyslexia” be diagnosed in children.

In order to adequately answer this question, it is important to understand the trajectory of development of literacy disorders in children. Continue reading How Early can “Dyslexia” be Diagnosed in Children?

The Test of Integrated Language & Literacy Skills (TILLS) is an assessment of oral and written language abilities in students 6–18 years of age. Published in the Fall 2015, it is unique in the way that it is aimed to thoroughly assess skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school age children. As I have been using this test since the time it was published, I wanted to take an opportunity today to share just a few of my impressions of this assessment.

The Test of Integrated Language & Literacy Skills (TILLS) is an assessment of oral and written language abilities in students 6–18 years of age. Published in the Fall 2015, it is unique in the way that it is aimed to thoroughly assess skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school age children. As I have been using this test since the time it was published, I wanted to take an opportunity today to share just a few of my impressions of this assessment.

First, a little background on why I chose to purchase this test so shortly after I had purchased the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5 (CELF-5). Soon after I started using the CELF-5 I noticed that it tended to considerably overinflate my students’ scores on a variety of its subtests. In fact, I noticed that unless a student had a fairly severe degree of impairment, the majority of his/her scores came out either low/slightly below average (click for more info on why this was happening HERE, HERE, or HERE). Consequently, I was excited to hear regarding TILLS development, almost simultaneously through ASHA as well as SPELL-Links ListServe. I was particularly happy because I knew some of this test’s developers (e.g., Dr. Elena Plante, Dr. Nickola Nelson) have published solid research in the areas of psychometrics and literacy respectively.

According to the TILLS developers it has been standardized for 3 purposes:

The testing subtests can be administered in isolation (with the exception of a few) or in its entirety. The administration of all the 15 subtests may take approximately an hour and a half, while the administration of the core subtests typically takes ~45 mins).

Please note that there are 5 subtests that should not be administered to students 6;0-6;5 years of age because many typically developing students are still mastering the required skills.

However, if needed, there are several tests of early reading and writing abilities which are available for assessment of children under 6:5 years of age with suspected literacy deficits (e.g., TERA-3: Test of Early Reading Ability–Third Edition; Test of Early Written Language, Third Edition-TEWL-3, etc.).

Let’s move on to take a deeper look at its subtests. Please note that for the purposes of this review all images came directly from and are the property of Brookes Publishing Co (clicking on each of the below images will take you directly to their source).

1. Vocabulary Awareness (VA) (description above) requires students to display considerable linguistic and cognitive flexibility in order to earn an average score. It works great in teasing out students with weak vocabulary knowledge and use, as well as students who are unable to quickly and effectively analyze words for deeper meaning and come up with effective definitions of all possible word associations. Be mindful of the fact that even though the words are presented to the students in written format in the stimulus book, the examiner is still expected to read all the words to the students. Consequently, students with good vocabulary knowledge and strong oral language abilities can still pass this subtest despite the presence of significant reading weaknesses. Recommendation: I suggest informally checking the student’s word reading abilities by asking them to read of all the words, before reading all the word choices to them. This way you can informally document any word misreadings made by the student even in the presence of an average subtest score.

1. Vocabulary Awareness (VA) (description above) requires students to display considerable linguistic and cognitive flexibility in order to earn an average score. It works great in teasing out students with weak vocabulary knowledge and use, as well as students who are unable to quickly and effectively analyze words for deeper meaning and come up with effective definitions of all possible word associations. Be mindful of the fact that even though the words are presented to the students in written format in the stimulus book, the examiner is still expected to read all the words to the students. Consequently, students with good vocabulary knowledge and strong oral language abilities can still pass this subtest despite the presence of significant reading weaknesses. Recommendation: I suggest informally checking the student’s word reading abilities by asking them to read of all the words, before reading all the word choices to them. This way you can informally document any word misreadings made by the student even in the presence of an average subtest score.

2. The Phonemic Awareness (PA) subtest (description above) requires students to isolate and delete initial sounds in words of increasing complexity. While this subtest does not require sound isolation and deletion in various word positions, similar to tests such as the CTOPP-2: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing–Second Edition or the The Phonological Awareness Test 2 (PAT 2), it is still a highly useful and reliable measure of phonemic awareness (as one of many precursors to reading fluency success). This is especially because after the initial directions are given, the student is expected to remember to isolate the initial sounds in words without any prompting from the examiner. Thus, this task also indirectly tests the students’ executive function abilities in addition to their phonemic awareness skills.

3. The Story Retelling (SR) subtest (description above) requires students to do just that retell a story. Be mindful of the fact that the presented stories have reduced complexity. Thus, unless the students possess significant retelling deficits, the above subtest may not capture their true retelling abilities. Recommendation: Consider supplementing this subtest with informal narrative measures. For younger children (kindergarten and first grade) I recommend using wordless picture books to perform a dynamic assessment of their retelling abilities following a clinician’s narrative model (e.g., HERE). For early elementary aged children (grades 2 and up), I recommend using picture books, which are first read to and then retold by the students with the benefit of pictorial but not written support. Finally, for upper elementary aged children (grades 4 and up), it may be helpful for the students to retell a book or a movie seen recently (or liked significantly) by them without the benefit of visual support all together (e.g., HERE).

4. The Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest (description above) requires students to repeat nonsense words of increasing length and complexity. Weaknesses in the area of nonword repetition have consistently been associated with language impairments and learning disabilities due to the task’s heavy reliance on phonological segmentation as well as phonological and lexical knowledge (Leclercq, Maillart, Majerus, 2013). Thus, both monolingual and simultaneously bilingual children with language and literacy impairments will be observed to present with patterns of segment substitutions (subtle substitutions of sounds and syllables in presented nonsense words) as well as segment deletions of nonword sequences more than 2-3 or 3-4 syllables in length (depending on the child’s age).

5. The Nonword Spelling (NS) subtest (description above) requires the students to spell nonwords from the Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest. Consequently, the Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest needs to be administered prior to the administration of this subtest in the same assessment session. In contrast to the real-word spelling tasks, students cannot memorize the spelling of the presented words, which are still bound by orthographic and phonotactic constraints of the English language. While this is a highly useful subtest, is important to note that simultaneously bilingual children may present with decreased scores due to vowel errors. Consequently, it is important to analyze subtest results in order to determine whether dialectal differences rather than a presence of an actual disorder is responsible for the error patterns.

6. The Listening Comprehension (LC) subtest (description above) requires the students to listen to short stories and then definitively answer story questions via available answer choices, which include: “Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe”. This subtest also indirectly measures the students’ metalinguistic awareness skills as they are needed to detect when the text does not provide sufficient information to answer a particular question definitively (e.g., “Maybe” response may be called for). Be mindful of the fact that because the students are not expected to provide sentential responses to questions it may be important to supplement subtest administration with another listening comprehension assessment. Tests such as the Listening Comprehension Test-2 (LCT-2), the Listening Comprehension Test-Adolescent (LCT-A), or the Executive Function Test-Elementary (EFT-E) may be useful if language processing and listening comprehension deficits are suspected or reported by parents or teachers. This is particularly important to do with students who may be ‘good guessers’ but who are also reported to present with word-finding difficulties at sentence and discourse levels.

7. The Reading Comprehension (RC) subtest (description above) requires the students to read short story and answer story questions in “Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe” format. This subtest is not stand alone and must be administered immediately following the administration the Listening Comprehension subtest. The student is asked to read the first story out loud in order to determine whether s/he can proceed with taking this subtest or discontinue due to being an emergent reader. The criterion for administration of the subtest is making 7 errors during the reading of the first story and its accompanying questions. Unfortunately, in my clinical experience this subtest is not always accurate at identifying children with reading-based deficits.

While I find it terrific for students with severe-profound reading deficits and/or below average IQ, a number of my students with average IQ and moderately impaired reading skills managed to pass it via a combination of guessing and luck despite being observed to misread aloud between 40-60% of the presented words. Be mindful of the fact that typically such students may have up to 5-6 errors during the reading of the first story. Thus, according to administration guidelines these students will be allowed to proceed and take this subtest. They will then continue to make text misreadings during each story presentation (you will know that by asking them to read each story aloud vs. silently). However, because the response mode is in definitive (“Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe”) vs. open ended question format, a number of these students will earn average scores by being successful guessers. Recommendation: I highly recommend supplementing the administration of this subtest with grade level (or below grade level) texts (see HERE and/or HERE), to assess the student’s reading comprehension informally.

I present a full one page text to the students and ask them to read it to me in its entirety. I audio/video record the student’s reading for further analysis (see Reading Fluency section below). After the completion of the story I ask the student questions with a focus on main idea comprehension and vocabulary definitions. I also ask questions pertaining to story details. Depending on the student’s age I may ask them abstract/ factual text questions with and without text access. Overall, I find that informal administration of grade level (or even below grade-level) texts coupled with the administration of standardized reading tests provides me with a significantly better understanding of the student’s reading comprehension abilities rather than administration of standardized reading tests alone.

8. The Following Directions (FD) subtest (description above) measures the student’s ability to execute directions of increasing length and complexity. It measures the student’s short-term, immediate and working memory, as well as their language comprehension. What is interesting about the administration of this subtest is that the graphic symbols (e.g., objects, shapes, letter and numbers etc.) the student is asked to modify remain covered as the instructions are given (to prevent visual rehearsal). After being presented with the oral instruction the students are expected to move the card covering the stimuli and then to executive the visual-spatial, directional, sequential, and logical if–then the instructions by marking them on the response form. The fact that the visual stimuli remains covered until the last moment increases the demands on the student’s memory and comprehension. The subtest was created to simulate teacher’s use of procedural language (giving directions) in classroom setting (as per developers).

9. The Delayed Story Retelling (DSR) subtest (description above) needs to be administered to the students during the same session as the Story Retelling (SR) subtest, approximately 20 minutes after the SR subtest administration. Despite the relatively short passage of time between both subtests, it is considered to be a measure of long-term memory as related to narrative retelling of reduced complexity. Here, the examiner can compare student’s performance to determine whether the student did better or worse on either of these measures (e.g., recalled more information after a period of time passed vs. immediately after being read the story). However, as mentioned previously, some students may recall this previously presented story fairly accurately and as a result may obtain an average score despite a history of teacher/parent reported long-term memory limitations. Consequently, it may be important for the examiner to supplement the administration of this subtest with a recall of a movie/book recently seen/read by the student (a few days ago) in order to compare both performances and note any weaknesses/limitations.

10. The Nonword Reading (NR) subtest (description above) requires students to decode nonsense words of increasing length and complexity. What I love about this subtest is that the students are unable to effectively guess words (as many tend to routinely do when presented with real words). Consequently, the presentation of this subtest will tease out which students have good letter/sound correspondence abilities as well as solid orthographic, morphological and phonological awareness skills and which ones only memorized sight words and are now having difficulty decoding unfamiliar words as a result.

11. The Reading Fluency (RF) subtest (description above) requires students to efficiently read facts which make up simple stories fluently and correctly. Here are the key to attaining an average score is accuracy and automaticity. In contrast to the previous subtest, the words are now presented in meaningful simple syntactic contexts.

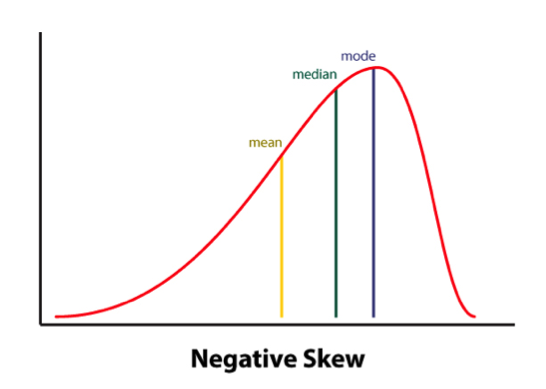

It is important to note that the Reading Fluency subtest of the TILLS has a negatively skewed distribution. As per authors, “a large number of typically developing students do extremely well on this subtest and a much smaller number of students do quite poorly.”

Thus, “the mean is to the left of the mode” (see publisher’s image below). This is why a student could earn an average standard score (near the mean) and a low percentile rank when true percentiles are used rather than NCE percentiles (Normal Curve Equivalent).

Consequently under certain conditions (See HERE) the percentile rank (vs. the NCE percentile) will be a more accurate representation of the student’s ability on this subtest.

Indeed, due to the reduced complexity of the presented words some students (especially younger elementary aged) may obtain average scores and still present with serious reading fluency deficits.

I frequently see that in students with average IQ and go to long-term memory, who by second and third grades have managed to memorize an admirable number of sight words due to which their deficits in the areas of reading appeared to be minimized. Recommendation: If you suspect that your student belongs to the above category I highly recommend supplementing this subtest with an informal measure of reading fluency. This can be done by presenting to the student a grade level text (I find science and social studies texts particularly useful for this purpose) and asking them to read several paragraphs from it (see HERE and/or HERE).

As the students are reading I calculate their reading fluency by counting the number of words they read per minute. I find it very useful as it allows me to better understand their reading profile (e.g, fast/inaccurate reader, slow/inaccurate reader, slow accurate reader, fast/accurate reader). As the student is reading I note their pauses, misreadings, word-attack skills and the like. Then, I write a summary comparing the students reading fluency on both standardized and informal assessment measures in order to document students strengths and limitations.

12. The Written Expression (WE) subtest (description above) needs to be administered to the students immediately after the administration of the Reading Fluency (RF) subtest because the student is expected to integrate a series of facts presented in the RF subtest into their writing sample. There are 4 stories in total for the 4 different age groups.

The examiner needs to show the student a different story which integrates simple facts into a coherent narrative. After the examiner reads that simple story to the students s/he is expected to tell the students that the story is okay, but “sounds kind of “choppy.” They then need to show the student an example of how they could put the facts together in a way that sounds more interesting and less choppy by combining sentences (see below). Finally, the examiner will ask the students to rewrite the story presented to them in a similar manner (e.g, “less choppy and more interesting.”)

After the student finishes his/her story, the examiner will analyze it and generate the following scores: a discourse score, a sentence score, and a word score. Detailed instructions as well as the Examiner’s Practice Workbook are provided to assist with scoring as it takes a bit of training as well as trial and error to complete it, especially if the examiners are not familiar with certain procedures (e.g., calculating T-units).

Full disclosure: Because the above subtest is still essentially sentence combining, I have only used this subtest a handful of times with my students. Typically when I’ve used it in the past, most of my students fell in two categories: those who failed it completely by either copying text word for word, failing to generate any written output etc. or those who passed it with flying colors but still presented with notable written output deficits. Consequently, I’ve replaced Written Expression subtest administration with the administration of written standardized tests, which I supplement with an informal grade level expository, persuasive, or narrative writing samples.

Having said that many clinicians may not have the access to other standardized written assessments, or lack the time to administer entire standardized written measures (which may frequently take between 60 to 90 minutes of administration time). Consequently, in the absence of other standardized writing assessments, this subtest can be effectively used to gauge the student’s basic writing abilities, and if needed effectively supplemented by informal writing measures (mentioned above).

13. The Social Communication (SC) subtest (description above) assesses the students’ ability to understand vocabulary associated with communicative intentions in social situations. It requires students to comprehend how people with certain characteristics might respond in social situations by formulating responses which fit the social contexts of those situations. Essentially students become actors who need to act out particular scenes while viewing select words presented to them.

Full disclosure: Similar to my infrequent administration of the Written Expression subtest, I have also administered this subtest very infrequently to students. Here is why.

I am an SLP who works full-time in a psychiatric hospital with children diagnosed with significant psychiatric impairments and concomitant language and literacy deficits. As a result, a significant portion of my job involves comprehensive social communication assessments to catalog my students’ significant deficits in this area. Yet, past administration of this subtest showed me that number of my students can pass this subtest quite easily despite presenting with notable and easily evidenced social communication deficits. Consequently, I prefer the administration of comprehensive social communication testing when working with children in my hospital based program or in my private practice, where I perform independent comprehensive evaluations of language and literacy (IEEs).

Again, as I’ve previously mentioned many clinicians may not have the access to other standardized social communication assessments, or lack the time to administer entire standardized written measures. Consequently, in the absence of other social communication assessments, this subtest can be used to get a baseline of the student’s basic social communication abilities, and then be supplemented with informal social communication measures such as the Informal Social Thinking Dynamic Assessment Protocol (ISTDAP) or observational social pragmatic checklists.

14. The Digit Span Forward (DSF) subtest (description above) is a relatively isolated measure of short term and verbal working memory ( it minimizes demands on other aspects of language such as syntax or vocabulary).

15. The Digit Span Backward (DSB) subtest (description above) assesses the student’s working memory and requires the student to mentally manipulate the presented stimuli in reverse order. It allows examiner to observe the strategies (e.g. verbal rehearsal, visual imagery, etc.) the students are using to aid themselves in the process. Please note that the Digit Span Forward subtest must be administered immediately before the administration of this subtest.

SLPs who have used tests such as the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5 (CELF-5) or the Test of Auditory Processing Skills – Third Edition (TAPS-3) should be highly familiar with both subtests as they are fairly standard measures of certain aspects of memory across the board.

To continue, in addition to the presence of subtests which assess the students literacy abilities, the TILLS also possesses a number of interesting features.

For starters, the TILLS Easy Score, which allows the examiners to use their scoring online. It is incredibly easy and effective. After clicking on the link and filling out the preliminary demographic information, all the examiner needs to do is to plug in this subtest raw scores, the system does the rest. After the raw scores are plugged in, the system will generate a PDF document with all the data which includes (but is not limited to) standard scores, percentile ranks, as well as a variety of composite and core scores. The examiner can then save the PDF on their device (laptop, PC, tablet etc.) for further analysis.

The there is the quadrant model. According to the TILLS sampler (HERE) “it allows the examiners to assess and compare students’ language-literacy skills at the sound/word level and the sentence/ discourse level across the four oral and written modalities—listening, speaking, reading, and writing” and then create “meaningful pro files of oral and written language skills that will help you understand the strengths and needs of individual students and communicate about them in a meaningful way with teachers, parents, and students. (pg. 21)”

Then there is the Student Language Scale (SLS) which is a one page checklist parents, teachers (and even students) can fill out to informally identify language and literacy based strengths and weaknesses. It allows for meaningful input from multiple sources regarding the students performance (as per IDEA 2004) and can be used not just with TILLS but with other tests or in even isolation (as per developers).

Furthermore according to the developers, because the normative sample included several special needs populations, the TILLS can be used with students diagnosed with ASD, deaf or hard of hearing (see caveat), as well as intellectual disabilities (as long as they are functioning age 6 and above developmentally).

According to the developers the TILLS is aligned with Common Core Standards and can be administered as frequently as two times a year for progress monitoring (min of 6 mos post 1st administration).

With respect to bilingualism examiners can use it with caution with simultaneous English learners but not with sequential English learners (see further explanations HERE). Translations of TILLS are definitely not allowed as they will undermine test validity and reliability.

So there you have it these are just some of my very few impressions regarding this test. Now to some of you may notice that I spend a significant amount of time pointing out some of the tests limitations. However, it is very important to note that we have research that indicates that there is no such thing as a “perfect standardized test” (see HERE for more information). All standardized tests have their limitations.

Having said that, I think that TILLS is a PHENOMENAL addition to the standardized testing market, as it TRULY appears to assess not just language but also literacy abilities of the students on our caseloads.

That’s all from me; however, before signing off I’d like to provide you with more resources and information, which can be reviewed in reference to TILLS. For starters, take a look at Brookes Publishing TILLS resources. These include (but are not limited to) TILLS FAQ, TILLS Easy-Score, TILLS Correction Document, as well as 3 FREE TILLS Webinars. There’s also a Facebook Page dedicated exclusively to TILLS updates (HERE).

But that’s not all. Dr. Nelson and her colleagues have been tirelessly lecturing about the TILLS for a number of years, and many of their past lectures and presentations are available on the ASHA website as well as on the web (e.g., HERE, HERE, HERE, etc). Take a look at them as they contain far more in-depth information regarding the development and implementation of this groundbreaking assessment.

To access TILLS fully-editable template, click HERE

Disclaimer: I did not receive a complimentary copy of this assessment for review nor have I received any encouragement or compensation from either Brookes Publishing or any of the TILLS developers to write it. All images of this test are direct property of Brookes Publishing (when clicked on all the images direct the user to the Brookes Publishing website) and were used in this post for illustrative purposes only.

References:

Leclercq A, Maillart C, Majerus S. (2013) Nonword repetition problems in children with SLI: A deficit in accessing long-term linguistic representations? Topics in Language Disorders. 33 (3) 238-254.

Related Posts: